Four Appreciations of Carolyn Kizer and Her Work

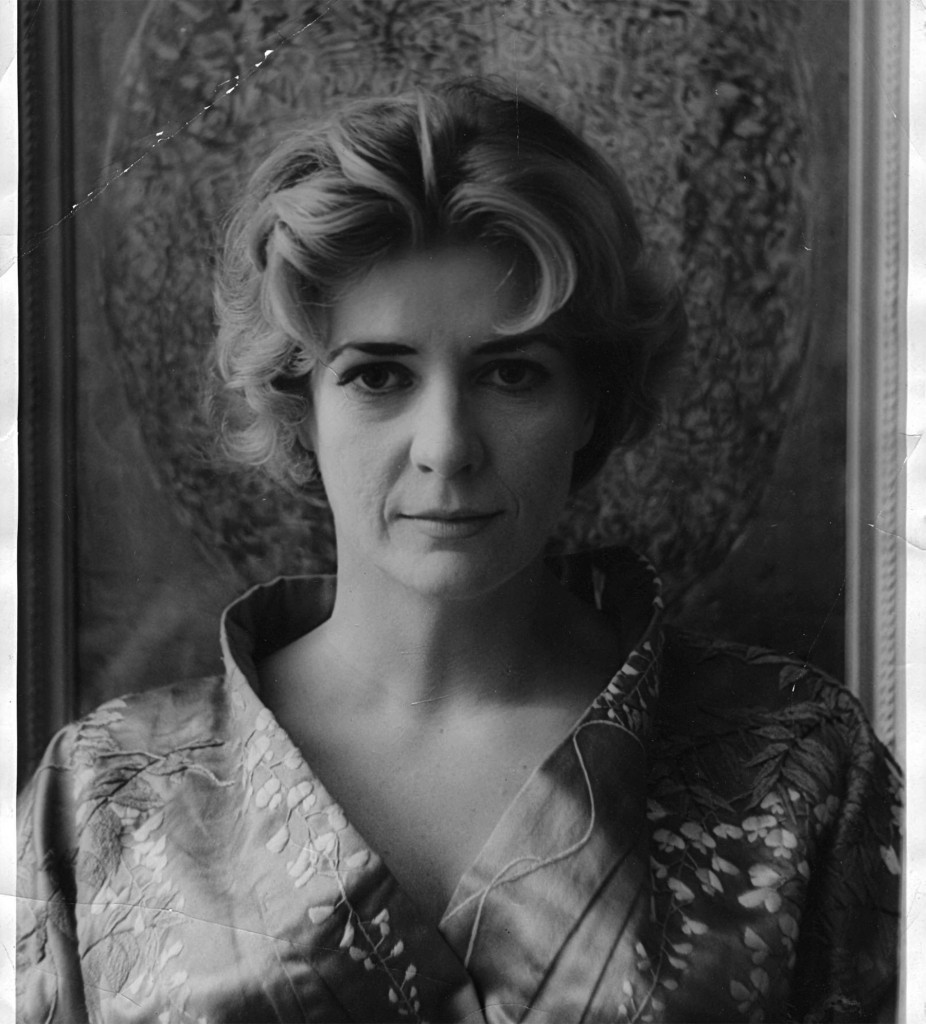

Carolyn Kizer was a force—not just in the U.S. or Northwest poetry scene, but as a total whirlwind presence of a person. Wearing her mink and a deep scarlet lipstick, she’d swoop into a roomful of people and swirl everyone under her spell. She called me Dahhling. Dahhling, could you find me an ashtray? She almost always had a cigarette in hand, which she used to punctuate sentences. A fellow Spokanite, she seemed to like returning to our town, a place with which she often said she had a love-hate relationship. “Some people from Spokane are insane salesmen / Peddling encyclopedias from door to door,” continues to be a favorite, crazy-true-to-this-day line of hers. I think her translations (many of which may be found in Carrying Over) are not nearly as well known as they should be. She had one of the most amazingly gorgeous and powerful reading styles/voices of anyone I’ve ever heard: that force revved up and unleashed on stage. Her poetry performances were more often recitations than readings. I’ll never forget her; she was truly a grande dame. Nance Van Winckel

—

I have often returned to Carolyn Kizer’s poem “Seasons of Lovers and Assassins,” which although dated June 5, 1968 (the date of Bobby Kennedy’s assassination) seems more articulate about the past ten years’ upheavals than most poems directly addressing 9/11, Hurricane Katrina, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and other overwhelming and bewilderment moments that have, as in Kizer’s poem, left us “to our fate,/ Wrapt in a caul of vulnerability.” The poem begins with lovers “safe from the wild storms off Cape Hatteras,” making their own storm on the beach, like Deborah Kerr and Burt Lancaster in From Here To Eternity. In an echo of her teacher, Theodore Roethke, they “swim to sleep, and drown.” After they dream, “another ocean wakes” them: news of the assassination. From here on, the sound of the poem rises to a bare, precise, majestic clarity:

Numbly we move to the noontime of our love:

The strip of rain-pocked shore gleams pallidly.

Fragments of broken palm-front fly like knives

Through tropic wind. Soon we bear star-shaped wounds,

Stigmata of all passion-driven lives

…

Marked lovers now, the moony night is ours,

Surf-sounds reminding us that good decay

Surrounds us: force which pounds on flesh or stone,

The slow assassination of the years.

Kizer has a public voice, one that hears its audience, like Pope. Her work is agile and present, never miserable, lonely, oracular, or visionary, but even in her essay-precise oratory she acknowledges the counter-poetry, listens to it (albeit with a coldness, a Chekhovian coldness that brings me closer as a reader). She is at once the poet she is, the lauded Spokane Augustan—and the poet she isn’t, the one from “To An Unknown Poet,” who, while the speaker is getting “an award/ from the American Academy/ and Institute of Arts and Letters” in a “noble old building,/ as pale as the Acropolis/ awash in a sea of slums,” is “far away, on the other coast,/ as far from our thoughts as Rimbaud/ with his boy’s face and broken teeth.”

I admire Kizer’s poems and career, how she has been able to speak to the importance of poetry, and act on it, helping found this magazine and the NEA, all very reputable activities, and yet in her work has never strayed far from the rude, rough mysteries of the imagination. Ed Skoog

—

Some years ago, at a rather swank party, I was shocked to overhear the hostess refer to someone as “a good bitch.” It took me a moment to realize that she was discussing kennel club business, and that the bitch in question was, indeed, a dog. Still, the shock of that word coming so easily from that educated, lipsticked mouth, stayed with me.

I felt a similar kind of shock the first time I read Carolyn Kizer’s poem, “Bitch.” The penultimate poem in her collection Mermaids in the Basement: Poems for Women, it follows many an elegant if angry recreation of classical mythologies. Those poems — for Sappho, for Hera, for Persephone — do a profound and political job of recasting old tales in new terms, holding our western literary traditions up to the burning light of the feminist magnifying glass.

But “Bitch” is another thing altogether. There is no liberating persona, no distancing history to soften this poem’s scrape and rasp. There are two simultaneous dialogues in it: one between the poet and an old lover she’s run into, and another between the poet and the “bitch” inside her, who, as in the conversation, is indeed a dog. The poem begins simply:

Now, when he and I meet, after all these years,

I say to the bitch inside me, don’t start growling.

He isn’t a trespasser anymore.

I’m going to assume that the speaker here is Kizer herself — famously beautiful, obviously successful, and, as evidenced in the preceding poems, ever so wise. When she says to that inner bitch, “he isn’t an enemy now,” the reader relaxes. So far, so good.

But while the old lovers continue their small talk, a different danger arises:

At a kind word from him, a look like the old days,

The bitch changes her tone. She begins to whimper.

She wants to snuggle up to him, to cringe.

Down, girl! Keep your distance

Or I’ll give you a taste of the choke chain.

The poet goes on to explain that the creature in question is “basically loyal” to her, but remembers the days of devotion to this other master, days when she survived on his “small careless kindnesses.” When, at the poems’ end, the old lovers part, the woman offers him the usual “regards to your wife,” while the dog gags on its chain.

Coming as it did after the lengthier, more elegantly crafted poems in Mermaids in the Basement, this 34-line, single-stanza poem shocked me when I first read it. It shocks my students when I teach it now. Yes, there’s that word itself, with all its electric charge. But what really delivers the blow, at least to this reader, is Kizer’s blunt illumination of one of the darkest corners of the female psyche. Protecting oneself in love isn’t simply a matter of steering clear of abusers, philanderers, and con artists. It’s a matter of containing and controlling your own worst self — the one that wants to be praised and petted and called a good girl, who feeds on the patient patronage of men. The bitch, according to Kizer in this brilliant, brave poem, is the enemy inside. While there may be no sending her away — we are, after all, all animals — self-defense requires that we recognize and stifle her unruly, self-sabotaging ways. Rose Solari

—

I came to Carolyn Kizer by way of Theodore Roethke, or to put it more precisely, through my reading of Roethke’s On Poetry & Craft, for which Kizer wrote an appreciative foreword. I love Roethke and loved the book, so my curiosity for Kizer’s poetry was piqued.

At the time I ordered Cool, Calm, & Collected, nothing I read pleased me. I started books and stopped. I returned books half-read to the library. Speakers were trying to charm me, make me like them. I found them taxing. I became especially fond of Jack Gilbert, not because his poems are beautifully crafted in the meditative style I love but because his speaker couldn’t care less whether I liked him or not. The poems struck me as honest and made no demands. They made excellent company.

As I made my way through Kizer’s collected poems, the first thing I noticed was how in my face they were. They dared me not to like them, to put the book down, and, as perverse as it may sound, I liked them for that. A steady stream of anger runs through her poetry: anger at her mother, anger at the cardboard-sided suburbs, and anger at the treatment of women. It does not let up. With no lack of sarcasm, the speaker ridicules men and women of all stripes. Her speaker is not afraid to be not nice. In fact, she’s not interested in being nice. She’s interested in calling it as she sees it. To make her case, she does not turn to the lyricism of her teacher, Roethke, but to the rhymed and metered argument of Pope.

One of Kizer’s primary subjects is the situation of women writers. In “Pro Femina,” a five-part poem published over three decades, woe is not only the male writer who crosses her path—Nietzche, Kierkegaard, and Strindberg, to name just a few—but also the female “toast-and-teasedale” sonneteers, the “middle-aged virgins,” and the “barbiturate-drenched Camilles.” Kizer’s willingness to be so unapologetic about her point of view takes nerve.

Since reading her book, I’ve sometimes wondered how much of Kizer’s directness comes from having studied with Roethke. Gilbert was one of Kizer’s classmates, as was James Wright; the class must have been extraordinary. For me, the thread that unites them is the integrity of their individual voices. They do not compromise. Kizer says in her foreword that Roethke believed his students’ “eccentricities” were part of their “true voice” and that he encouraged his students to write like no one but themselves. As a teacher herself, Kizer was not interested in having her students write the perfect “workshop poem, in which everything eccentric or outrageous has been ironed out,” the kind of poem you read and think, “Very nice,” and never think about again. Kizer wants poems that present a challenge.

When I read Kizer, who was a major player in feminism’s second-wave, I argue with her, half-agree with her, get tired of what often seems like a loud and heavy hand as is my luxury. Kizer is a poet who gets herself in the game and says exactly what she thinks. She does not sit on the side-lines, watching, casting judgment, smoothing her skirt. She does not smile politely as she comes down from the stands. She’s in there, throwing the occasional elbow, ready to foul or overshoot the hoop. She’s on the court because she wants to change the rules. Joelle Biele

—

The appreciations from Ed Skoog, Rose Solari and Joelle Biele all appeared originally in the Spring & Summer 2011 print edition of Poetry Northwest. for more about and by Carolyn Kizer, visit that page. The piece from Nance Van Winckel appears here for the first time.