A Character in Search of an Author

by Kary Wayson | Contributing Writer

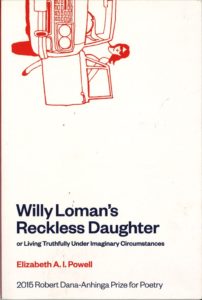

Willy Loman’s Reckless Daughter or Living Truthfully Under Imaginary Circumstances

Willy Loman’s Reckless Daughter or Living Truthfully Under Imaginary Circumstances

Elizabeth Powell

Anhinga Press, 2016

Elizabeth Powell’s Willy Loman’s Reckless Daughter is, to its credit, difficult to characterize. Less conceptual art than concept art (think of the creative team on Mad Men putting together a presentation for a client), the process itself is a large part of the result. This book gives generously of the pleasure of watching a mind work. Powell’s project—the one her book manages through four sections, 105 pages, and in how many different directions—is to take her own story, particularly her relationship with her dead father, and apply it to the dialogue and structure of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman.

Powell’s Reckless Daughter energetically inhabits, expands upon, and grows Miller’s Death of a Salesman. More than just using the play as a template for her work, Powell makes her narrator an extra, invisible, and heretofore unknown, unwritten character–the daughter of Miller’s famous delusional loser, Willy Loman. Powell’s book sets out to explore a Great Idea (that is, to test the thresholds of Miller’s play with the eyes, ears, fingers, and nose of Powell’s own familial experiences) and does so thoroughly, lavishly, and to my repeated experience—I read the book, read the play, then read the book again—successfully.

Miller’s stage directions provide the connection between Powell’s life and the action of the play. The directions read, “Whenever the action is in the present, the actors observe the imaginary wall lines…but in the scenes of the past, these boundaries are broken, and characters enter or leave a room by stepping ‘through’ a wall onto the forestage.” Interesting here that present-time action requires the actors to observe the imaginary, while past-action—ghost action—is indicated by a willful disregard of the imaginary.)

The first poem of the book, “Autocorrecting the Lyric I,” written as a lyric essay, a form that passes for prose and poetry, sets up the lyric facts for all that follows—the narrator is half Jewish, half WASP who can pass for either, or rather, neither, showing up as gentile among Jews and as a Christ killer to “the R.C. boys.” Either way, she says, “Acting is a favored mode…I’ve had practice passing as a Jew and passing as a WASP…I have become kind of good at doing this passing, though the one identity is always trying to autocorrect the other.” Later in the poem, we get the wonderful lines, “I am an Elizabeth…I autocorrect into an electric elsewhere/ I am also Ann And Another.” Later in the same piece, we find this: “the fact that I had absorbed my lost twin in utero.” With that we understand that this missing other is literal—and that the missing twin, or the sense of him, is cause for both strength and grief in the survivor (who, just by being, consumed her other). In the poems that follow the narrator is left alone and still hungry, “a character in search of an author.”

The poems throughout the book work as experiments that enlist the play’s dialogue, the art of acting, and especially the exercises of improvisation—the book’s subtitle is Living Truthfully Under Imaginary Circumstances. In Section 1, Powell’s poems based on exercises for improv actors are among the strongest in the book, filled with admirable turns of phrase as well as many lovely instances of lyrical ideation. For example, In “The Animal Experiment,” we get “the magic if turning into the magic is.” And then in “Sense Memory,” she gives us “NOT ACT but ACTUAL. I am trying to WILL an EMOTION by inhabiting objects like space and time and a hallway.” Powell’s creation-work—making space, place, and/or time into habitable objects is just one side of the effort—in the same poem she accuses herself of an opposite impulse towards (self) destruction:

So I/you dared each blessed gift from creation to show you that it rally loved you by making choices toward the way you really didn’t want to go. You let the darkness push the automatic button. Bad idea.

Again, it’s interesting, this idea of an imaginary boundary. The two words seem like worlds at war but act as codependents: one can’t live without the other—much like if and is and I/you—making, among other things, belief.

Powell follows her longish first section with a second short one, a sequence of sonnets called “The Understudy’s Soliloquies.” In this experiment—and it does feel like an experiment—Powell feeds her topic through the mill of form. In these poems the rhymes are head-on—a favorite plows from “furrows” to “fjord” to “reward”; another gives us the father’s (and/or Willy Loman’s) mistress, “like a newlywed to the newly dead.” The poems here do feel forced, but perhaps that’s in their favor—and it may be Powell’s intent, as if to say: “look, you want me to do it in form? Ok here—I did it to form.”

The poems in section three leave the sonnets behind, but retain their sonic impulses. These poems also ask questions of identity, most urgently: who is the identity inhabiting the I? Is it Powell herself? Her narrator? Her sublimated twin, her un-authored character? Powell uses this questioning to good effect, and throughout the first part of this section of poems, the I is the I of the newly dead father: “When they pronounced me DOA, the glass doors/ of the hospital opened for me like jaws,/ as they rolled me to the morgue.”

As the poems progress, the father drops back into third person. For instance, in a sequence called “What Death Said,” the father becomes a man called Lewis Itkin, and Death HIMSELF moves left to inhabit the I. And so on: the poems progress smartly through “How to Sew an Unhemmed Day,” in which the speaker really could be any one of a number of characters, and then goes back to our original narrator in the poem that follows. I say original about the narrator here, but I don’t mean unchanged. By the time we finish these poems, Willy Loman’s “reckless daughter” has actualized enough to become the voice, both measured and heedless, of the (rhyming, couplets) last section.

In David Mamet’s 2005 essay for The Guardian, he posits that Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman cannot be categorized as one of the great (say white, say WASP) American plays because the play, “it’s author, setting, and subject: the business, and the agony of assimilation are all Jewish.” He says, “Miller’s master creation, Willie Loman, is, to any Jew, unmistakably a Jew.” In that essay, Mamet even goes so far as to leapfrog the constraints of chronology by calling upon the reader to study Allen Ginsberg’s famous poem, “America,” written 7 years after the play’s first production, as the original text to which Death of a Salesman should be read as a response. Just consider that for a minute—as a whopper example of a lyrical idea, one that disregards both space and time. However, Mamet’s idea lurks effectively behind the scenes of Powell’s best experiments, poems that can themselves be read as original sources for Miller’s play.

—

Kary Wayson is the author of two collections of poetry, American Husband, which won the Charles Wheeler Prize from the Ohio State University Press, and Via Maria Materi, recently chosen as a finalist for Four Way Books’ Levis Poetry Prize and the University of Wisconsin’s Brittingham and Pollak Prize. She’s also author of a chapbook, published by LitRag Press, called Dog & Me.