Damaged and Open: On Sara Moore Wagner’s Hillbilly Madonna

by John McCarthy | Contributing Writer

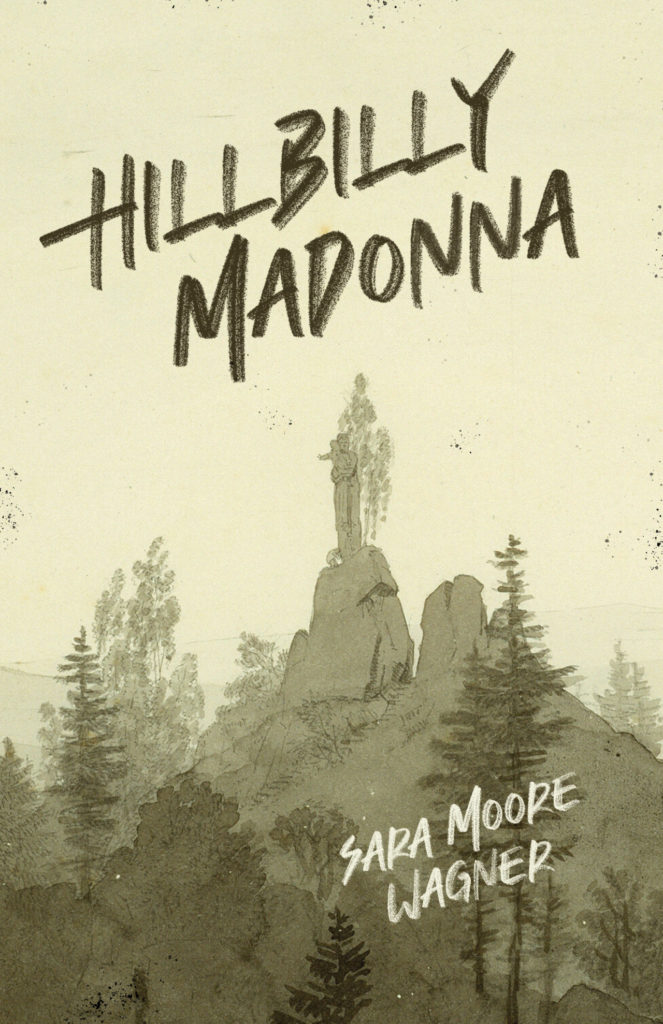

Hillbilly Madonna

Sara Moore Wagner

Driftwood Press, 2022

In an introductory letter folded and placed into Sara Moore Wagner’s second collection, Hillbilly Madonna, she writes that she wants to “pass on only beauty to the next generation.” She goes on to depict an Appalachia that is as much an illustrative rendering of a roughshod landscape as it is an inherited life of personal struggle and genuine crisis. But this book does not exploit trauma for the sake of validation. No, Hillbilly Madonna grapples with something much more complex: the interrogation of ancestry in all its dualities—from love and compassion to addiction and abuse—as it intersects with historical gender roles and experiences. With this book, Wagner creates an artifact that uproots the parts of ancestry that do not need to be reproduced, presents them as experiences to learn from, and opens a door for a new generation to enter a new way of life that isn’t “chained to anything.”

Roots, both literal and figurative, appear frequently in these poems. In “Blood from a Turnip” Wagner writes:

[H]ow much

of him is left in me. How much

will I still need to cut away.

And, directly following that, “Autoimmune Anemia: Transfusion”:

To be a daughter who tends.

to have a father who wants

tending or burial. For you to be that father

or little root in the dry earth.

And later on in “On Cutting Him Off”:

If my father has tied me

to the tree by the hair, it’s only natural

to cut it off.

These examples highlight the duality of experience, of being rooted to a place, a family, and an individual, gendered body which is simultaneously uprooted by the destruction of place, and by a family breaking apart or tearing itself apart. The work takes as its subject self-sabotage, or the harmful ways in which that self-sabotage is the result of internalized patriarchal modes.

For instance, in “Sometimes the Right Light,” Wagner writes: “I am a shadow on the landscape, / invasive.” And later in the poem, we see the ways in which pain has been passed down through the generations in lines like “how your mother can break before / you, even before you break her yourself.” Wagner shows how the women in her family are “marked / for loss. This mother who’s ripe / for chopping.” But Hillbilly Madonna does a great job at resisting and reclaiming stories that have been threatened by loss. There is nothing invasive about them. They are necessary.

Struggle against the patriarchy is coupled with a critique of the faith that has made itself an organic part of Wagner’s Appalachia—as much a part of the region as its animals, trees, and plants. This critique makes a haunted reliquary of the region where faith and masculinity combine to create something violent and damaged, broken and wounded. Take for instance this illustration from “Heroin as Women’s Work”:

I’ll show you what I’ve learned

about God: that a man will take you

no matter how beautiful

you make the world.

Take also these lines from “Witch’s Mark”:

[M]y father

is the kind of man, like God,

who would give me the world

damaged and open

Which lead nicely to this prophetic wish in “Girlhood Schism”:

I want to get out of this

pipped coffin my father built

from junkyard parts.

For many decades, the masculine practice of regional poetry tends toward romantic elegy or a lamenting romanticism of the past—which is neither good nor bad—just observation. Recent examples include Matthew Wimberley’s All The Great Territories (Southern Illinois University Press, 2020) and Austin Smith’s Almanac (Princeton University Press, 2013). Earlier examples include work by B.H. Fairchild and Larry Levis. But Wagner is unafraid to offer an interpretation that adds, compliments, deepens, and ultimately, complicates those interpretations.

In comparison and conversation with other works, Hillbilly Madonna is most reminiscent of Essy Stone’s prize-winning collection, What It Done To Us (Lost Horse Press, 2016), in which the realia of rural Appalachian life is brought to the forefront through specific metaphors and lyric narratives that bring the reader as close as possible to lived trauma. Both of these authors bring to the page a specific lineage of trauma and explores its effects on families and the ability of each speaker to encounter and relate to the world.

Additionally, Hillbilly Madonna makes a good companion for Shaindel Beers’ Secure Your Own Mask (White Pine Press, 2018), Sandy Longhorn’s Blood Almanac (Anhinga Press, 2006), and, most recently, Joy Priest’s Horsepower (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020) insofar as the matriarchal point of view reclaims the landscape itself and unravels our overly romanticized history with the bucolic. The speakers and narratives in these collections counteract the often gendered lamentations of midwestern or appalachian settings and give credence and voice to the omitted or marginalized voices and stories that inhabit these poetics of place as frequent as the masculine need to venerate a place to the way it once was.

The final poem in Hillbilly Madonna, “Let’s Wait to Bathe Her,” concludes with a double birth. The first is the literal birth of a child; the second—the figurative birth of self-realization and -actualization:

[M]aybe I can be what she needs,

or else, what I see

when I look in the mirror—

clean.

Wagner’s image of the hillbilly Madonna is the incarnation of the paradoxical, impossible role which women are expected to fill. A role that requires holiness measures women against an impossible standard, a standard which categorizes women as unclean or impure when they inevitably fall short of saintliness. That role and its standards are exactly what Wagner exorcizes from her lineage in this book, an exorcism which is baptismal in its effect.

From surprising similes like “Morning / spreads like the thin veil of blood around the brain” to enjambed lines packed with tension and dual (and dueling) meanings, Wagner shows an intelligent and passionate command. In “Captivity Narrative,” Wagner proclaims: “[I]t never matters / how you get out, only that you / always do.” The ultimate testament of Hillbilly Madonna is one of reassurance and hope, and Wagner is confident in her manifestation of the life she desires.

—

Sara Moore Wagner is the author of three full length books of poetry, Lady Wing Shot (winner of the 2022 Blue Lynx Prize, forthcoming from Lynx House press in 2024), Swan Wife (winner of the 2021 Cider Press Review Editors Prize) and Hillbilly Madonna (2020 Driftwood Press Manuscript prize winner), a recipient of a 2022 Individual Excellence Award from the Ohio Arts Council, a 2021 National Poetry Series Finalist, and the recipient of a 2019 Sustainable Arts Foundation award. She is the author of the chapbooks Tumbling After (Redbird, 2022) and Hooked Through (Five Oaks Press, 2017). Her poetry has appeared in many journals and anthologies including Sixth Finch, Waxwing, Nimrod, Western Humanities Review, Tar River Poetry, and The Cincinnati Review, among others. She lives in West Chester, OH with her filmmaker husband and their children, Daisy, Vivienne, and Cohen.

John McCarthy is the author of Scared Violent Like Horses (Milkweed Editions, 2019), which won the Jake Adam York Prize. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in 32 Poems, Alaska Quarterly Review, Best New Poets, Cincinnati Review, Gettysburg Review, Ninth Letter, Pleiades, and TriQuarterly. He received his MFA from Southern Illinois University Carbondale. John is the Managing Editor of RHINO.