Clear Air Turbulence: Reflections on a Mountain as Memorial Ground

by Kevin Craft | Contributing Editor

This essay is the first installment of Land/Form, a new series exploring topics in geo-poetics. Our focus here is to publish longer essays of a lyrical, exploratory nature, mapping lived experience, big or small, with the topography of selected poems. Our goal is to offer a different kind of close reading, one that borrows equally from landscape and lineation, showcasing how poetry deepens our engagement with places—those loved, lost, or previously overlooked.

If you have a proposal for the series, please query us on Submittable, or at landform@poetrynw.org.

It’s late summer—September 2001—open season in the North Cascades. Goats have grown a thick new coat of fur. Bears roam kaleidoscopic meadows, sniffing out tubers, scouring the huckleberry bushes clean. Migrant warblers have packed up shop, their restless compasses tuned to the tropics. Not least, first frosts have killed off the mosquitoes. Between summer swarms and winter snows, a walker in the high country can walk in peace.

In pre-dawn gloom the streets of Capitol Hill are mostly empty, though I can hear—louder now for the lack of ambient veneer—the dull roar of the interstate slicing through the city. I throw my pack in the car. This time of year, it’s always at the ready. I’ve lived in Seattle long enough to know the ritual: take the good weather while you have it. High pressure ridge offshore, uninterrupted sun in the forecast—seize the day. I’ve always found it difficult to sit still when the sun is shining—long before I moved to the Northwest. It may be the reason I moved here in the first place. Mountains stacked in every direction. One look at a clear horizon unsettles me for the rest of the day.

My destination this restless morning: the Mountain Loop Highway—an exuberant name for a half-paved, half-gravel circuit winding through the Cascades about hour or so northeast of Seattle. It follows a riparian trajectory out of the lowlands into the heart of the range, connecting the once-bustling mining town of Monte Cristo to the port of Everett. That town vanished long ago, leaving shards of abandoned infrastructure—train track, mill wheel, saloon and brothel—to molder in second growth forest. But the ghost town and its tenuous claims are not my objective today. A clear day ahead, I set my sights a little higher. Today is the day I will tackle Mt. Pugh.

Known to the Sauk peoples as Da Klagwats, Mt. Pugh gets its contemporary moniker from John Pugh, who in 1891 settled in a cabin at the base. Pugh marks the western boundary of the Glacier Peak Wilderness, one of several giants in the Sauk River drainage notable for what mountaineers call prominence. Rising abruptly from the U-shaped trough of the river valley, Pugh tops out at 7215 ft, a thousand feet higher than any other nearby summit. It stands alone—an island of stone and air—steep, forbidding, aloof. Along with Sloan Peak, White Chuck and Mt. Forgotten, all of which feed the gravel-braided Sauk, Pugh anchors a hopscotch archipelago of shapely spires to the west of Washington’s third highest volcano. It’s just tall enough to be visible from high points in Seattle—though it takes a careful eye to locate Pugh’s pyramidal summit behind the many intervening ridges.

Driving north I watch the Cascades emerge from twilight—each fanged silhouette outlined in rose and gold. By the time I cross the meandering sloughs of the Snohomish River, daybreak is flooding the plains. On the radio, staccato trumpets of Weekend Edition muster my divided attention. Scott Simon is relishing the respective semi-final exploits of Venus and Serena Williams—the two sisters on a collision course toward their first ever match up in a US Open Final later this very day. Then, in a corner of the windshield, slow movement catches my eye. Great blue heron. It crosses the highway methodically, neck tucked in flight posture, wings spread out like awnings, quietly beating its way upriver, unperturbed by the traffic below. I have that old premonition in my bones—wild joy for the high clear country ahead.

Joy, that is, tempered by solemnity. A week ago I learned that a dear colleague had died suddenly, drowned in a rip tide off the Oregon coast. Bill Carpenter was a beloved teacher at Everett Community College, a specialist in American literature. Our offices adjacent, we’d often chat between classes about pet projects or plans for the weekend, how to squeeze out time for research and writing even as we hustled to secure enough adjunct work to feed our families. A week ago, he was on vacation with his. At some point he faced a parent’s worst fear: two sons in distress, flailing in the undertow, he dove in after them, somehow managing to save them at the cost of his own life. The current must have been ferocious that pulled him out and under. His body was never recovered.

I’ve been thinking about him all week, wondering if he realized his sons were safe, thinking of the boys’ utter bewilderment at the loss of their father in one desperate day. Heroism, we call it, to mollify an otherwise inexpressible grief, the accident that defies explanation. Driving to the trailhead this morning, I think of him pacing back and forth in front of the classroom whiteboard, preaching transcendentalism to an empty room.

From a hiker’s perspective, Pugh represents the next leg up. It’s not an easy climb, though in favorable conditions anybody reasonably fit can tackle it. The trail begins in old growth forest dominated by Douglas fir, crossing several streams as it winds toward a solitary lake. From there the climbing kicks into high gear, zig-zagging through spectacular avalanche meadows to reach a notch in the ridge known as Stujack Pass.

This is where the official trail ends, and the test of nerves begins. A boot path continues north through the pass up a steep shoulder populated by subalpine fir, then swings back south along a knife edge ridge, rounding several knolls before crossing a narrow bridge, two-feet wide, flanked by fall-away fault-line gullies, at which point you find yourself facing a cliff. Where to now? Straight up, hands and feet required. The scramble route picks a delicate way through quartzite slabs to gain the upper heather meadows where the boot path resumes. From there it’s like climbing stairs in a skyscraper to reach the top—5300 feet, all told—all in a good day’s work.

Or so I’ve read. I’m not sure I like the sound of that “knife-edge ridge,” but here I am, ready to give it try. This is years before trip reports and weather satellites and handheld GPS devices could map and disseminate a hiker’s every move. You read a short description in a book, picked up a Green Trails map (or trusted your own internal compass), and away you went. Whatever the trail had in store for you that day is what you got.

Of course, a trail is a luxury on a mountain like Pugh. We owe this one to the Forest Service and the construction boom in fire lookouts a century ago—they plotted the original course, just about the only course possible for a biped, threading the eye of the pinnacle, as it were. The lookout on Pugh would have a commanding view of the surrounding territory—from Glacier Peak to the Salish Sea—much of it still wilderness today.

By the time I pull into the small trailhead lot, sunlight is blazing across the valley, but the west side of Pugh still sits in shadow. That’s good. In the overhanging cool of morning, I make it to the lake in no time—carried forward on that rhythm a walker slips into when objective matches terrain. At the lake sunlight finally pierces the canopy, turning the reed-fringed shoreline shades of mustard and gold. In the meadows higher up, I find my breathing rhythm—slower, more methodical—aiming for the notch at Stujack Pass. In this patient stride I sometimes find myself reciting poems—under my breath, at first, more boldly at a turn in the trail. It’s a kind of work song, I suppose—that old traveler’s habit of turning monotony into rhythm and blues. I take whatever comes to mind and fold it into my walk. Today, thinking of Bill, “One Art” presents its switchback charms. The art of losing isn’t hard to master, I mutter, kicking a stone off the trail.

Through Stujack Pass the panoramic north comes into view—White Chuck, Koma Kulshan, Shuksan, the border peaks of British Columbia basking in unusual clarity—unusual, that is, for this time of year, when skies are often marred by wildfire smoke or city haze. Not today. Warm air rises from the valley. There’s a red-tail climbing a thermal spiral, turbulence hiding in the clearest sky.

Now practice losing farther, losing faster . . . I find the anticipated boot path rounding the north shoulder of the ridge, one step up for each step forward. Paintbrush clings to meadow slopes in bright red clumps. The pungency of subalpine fir stirs in me that happiness rooted in belonging—the opposite of ecstasy, which is (by definition) placeless, buffeted by its own displacement. Here, this morning, sun and soil and boot sole conspire in the fragrance of this particular slope. What I feel is fullness, every sense brimming.

Until I reach that knife edge, then it might as well be ecstasy or euphoria that carries the day. It’s a long way down on either side. Still, the path is clear. I plant one foot before lifting the other, a Vibram lug my primary contact with the planetary crust. The passage through the cliffs stiffens my jaw, presenting here and there an option one might not want to take. I test each rock before proceeding—a gulley has its rip tides too. Apparently, there was once a fixed rope that guided lookouts through this section, but that’s long gone. Hand over foot, mind over matter—or rather, hand in foot, mind in matter. All my fears turn to loose gravel on a thinning ledge. And then I’m through. Heather benches greet me on the other side like the welcome mat of heaven, still bright with flowers, pink and white. The summit block spins into view. Twenty stairmaster minutes later I’ve arrived.

From a distance, Pugh resembles a pair of shoulders shrugging off a clean decapitation. Up close, one lands among a jumble of quartzite slabs, tossed and tilted like a giant’s playpen. What looks orderly from afar is anything but. On a level patch beside this mayhem, I find the the old lookout—what’s left of it, that is, third of its kind on this spot—concrete foundation blocks, some cable twisted out of rust, the occasional nail. The first lookout was a simple tent; the second, a wood cabin with cupola, was struck by lightning. The third version, another cupola-topped cabin, was deliberately destroyed in 1965, leaving nothing but a one-room ghost town, all that old-timer scrutiny glaring in absentia. And look! My last, or / next-to-last, of three loved houses went. I think of Bill as I run through the poem again, reciting it to a hopeful chipmunk, to the red-tails circling below.

Lunch is a cramped banquet of salami and salutations as first one party then another arrives—six of us spreading out a vertiginous picnic. The others settle in among the giant boulders, leaving me to my ruined lookout rumination. With binoculars I scry the glaciers on Dakobed, the “great parent,” as Glacier Peak was known to Indigenous peoples. In late summer the glaciers are heavily crevassed, a corrugated mess of blue-grey gills gaping from thinning spools of white.

I take out my camera, a Pentax K-1000. It’s a handsome affair—all rounded edges, black leather casing with chrome trim. The advance lever and rewind crank are manual, and the spring-loaded shutter closes with a satisfying thunk. There’s a dime-sized battery to charge the galvanometer needle in the viewfinder, which swings vertically between +/-, otherwise no battery needed. The old SLR camera is a marvelous hand-operated machine.

I’ve only brought one roll with me today—yellow canister, 24 exposures, 400 ASA. Between ladders of ice above and ribbons of river below, fifteen shots remain. Summer won’t last forever. I take one final summit snap from the lookout’s point of view—the foreground spine of Lost Ridge leading straight into the heart of the big volcano, Dakobed filling the frame—then head back the way I came. Downclimbing the cliff passage takes every ounce of care I have left. Once through the difficulties, I am overcome with relief and fatigue.

Before the drop to Stujack Pass, I find a little knoll just off trail to sit for a spell, basking in satisfaction, soaking up the afternoon sun. On the slope just below, I spot a group of mountain goats—all insouciance and photo opportunity—grazing nimbly at their meadow buffet. I take out the Pentax, snapping those miniature goats into place. Then I lean back into the slope, close my eyes, feel the spinning of the earth, sunlight warming my lids. Minutes tick by like days . . . and then I’m upright again, gliding into the solemn joyful zig zag home. A barred owl calls from further down the trail. Shadows fill the valley as I descend, the lake now shimmering twilight blue.

Unpacking in Seattle later that night I can’t find the camera. I ruffle through my gear again, troubled by not seeing what ought to be there. I think back to when I’d last used it: the mountain goats, that sunny nap on the ridge above Stujack Pass. Could I have left it there? The clarity of the day dissipates in turbulence. So many things seem filled with the intent to be lost—I feel a little stupid leaving my camera on the mountain. I let my satisfaction get the better of me—never a smart move in the mountains. Da Klagwats has clawed back her own.

I console myself watching the late news: Venus Williams beat Serena in the US Open Finals—the art of losing and the art of winning braided in the same family tree.

I don’t have time to dwell on the missing camera. Two days later, on September 10, 2001, I’m supposed to meet Dan Lamberton at the trailhead for Mt. Daniel, a popular climb in the heart of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness.

Dan is an old friend who, unlike me, was born and raised in Washington state. He grew up in the Okanogan Highlands near the Columbia River, not far from Grand Coulee Dam—on which he once worked, in the 60s, helping to install new turbines. He often told stories of his days doing trail work in the Pasayten wilderness, or climbing the routes that Fred Becky pioneered in the Pickett Range. A man of amiable humility, you’d have to pry these stories out of him, at least at first. Once Dan warmed to a conversation, however, you never knew what you’d get. He was always surprising me with tales of some job or adventure he’d had—teaching on Navy ships, archeological digs in Central America—the treasury of his experience seemed bottomless. So when I discovered that he’d never attempted his namesake peak, I saw an opportunity, and proposed an excursion fill this lacuna in his education.

Mt Daniel is a gorgeous massif, a variegated stack of ecosystems straddling the Cascade Crest. The north and west faces drain into the Skykomish River and out to Possession Sound in the Salish Sea, while the south and east sides form the headwaters of the Cle Elum River, which joins the Yakima on its journey to the Columbia and from there, back through the crest again to the Pacific. Embracing a fair quarter of the Evergreen State, Mt Daniel is a watershed mountain, indeed.

The summit ridge is broad, a spine of snow and ice punctuated by five distinct pinnacles, the tallest topping out at 7960 ft. Seen from a distance, the east face resembles a finback whale, broad and generous—or rather, a pod of finbacks lined up and surfacing in succession. From any angle Daniel pitches its five-ring circus tent in distinct fashion, spinning out an interlocking carousel of cascades and lakes. But it is difficult to see from a distance, until you get up in the high country, from which vantage—like an understated friend—it is more readily appreciated.

The plan is to meet at the trail head. In early season Mt. Daniel is a challenging climb, generally requiring crampons and ice axes if not ropes for the upper snowfields. In late summer, there’s a hardscrabble boot trail to follow most of the way. Or so we’re told. I repack my gear into a larger backpack. We plan for two or three nights out.

At the rattled end of a long slow drive on pitted, potholed Cle Elum River Road, I pull into the parking lot and let out a sigh that mingles with the whiff of overheated engine. It already feels like an arduous journey. I walk around the lot, stretching my cramped legs, readjusting my pack. Dan pulls in a half hour later. He’s brought two additions to our climbing party—his son Seth, and Seth’s girlfriend, Noa. By the time we hit the trail, it’s already late afternoon. We opt for a short put-in two miles up the trail to the first good camps at Squaw Lake. Around the campfire that evening, Dan tells a story about a job he once had salvaging dead cattle parts to feed to lions in a renegade western zoo. Another tale I’ve not heard before. A man is a stack of ecosystems, too.

I wake in a scrim of amniotic gray, sleeping bag drawn around my head like a down cocoon. For a moment I just lay there, taking in sounds—the snap of a twig, the screed of a chickaree, the chastising call of a Steller’s jay—the forest taking shape in syllable and decibel, prying itself loose from the babble of a vanishing dream.

I stick my head out of the tent in time to see the last stars fizzle in the widening dawn. Water bubbles on the propane stove—Dan is making coffee. 6:00 am. I pull on my boots, wander off to relieve myself beneath the outhouse of a towering fir. There’s a chill in the air—September at 5000 feet. I scout the perimeter of camp for more kindling. A little fire will do us good.

While we wait for the others to awake, I tell Dan about my lost camera. He tells me about Kodak Peak—a knoll at the headwaters of the Little Wenatchee which early Forest Service surveyor Albert Sylvester named in honor of an assistant who had left his camera there. I’m glad to hear there’s a history of absent-mindedness in these hills, the legend already written to which I can affix my loss. In that case, I add, forget Stujack Pass. It’s Pentax Pass from here on out.

Fire licks the chill out of the air. Our conversation circles back to Bill Carpenter. Sadness flickers in the heart of the flame. Dan adds to it the story of an old friend who, decades ago, took his two sons and their two friends camping. A freak windstorm in the night toppled a tree which landed on the boys’ tent, killing the other boys while sparing his sons, who only missed being crushed themselves because they slept curled up in the fetal position.

I can’t begin to fathom the legacy of sorrow and guilt that man has had to live with ever since, returning home without his friend’s two boys. Fate shocks us with its casual selectivity. Mountains exhibit that lesson routinely—climbers lost every year to avalanche or mishap. Gazing up into the brightening canopy, I study our possible futures. Mortality lurks in every branch and bole.

The younger set stirs in their tent. Here and there a nuthatch warms to its toy soldier reveille, tin trumpets blaring around the lake. Is there a sweeter sound than the tiny brazen courage of a nuthatch to fill a forest morning? Sunlight sweeps downhill, filtering through mountain hemlock, spotlighting patches of sword fern in the understory. I feel that migratory itch building in my bones. After breakfast we pack up camp and hit the trail, cheerful for another cloudless day.

On the ridge below the singular spire of Cathedral Rock, the access trail we are following joins the PCT. I meet a thru-hiker—a woman, solo—rarer in the days before Cheryl Strayed’s Wild made the bestseller list. When did you start out? I ask, always eager for trail reconnaissance, however distant and useless. April, she replies, her eyes brimming with the miles she’s walked from Mexico to this very spot. We pause a minute to admire the blaze of huckleberries brushing at our knees. They may be past their prime, but they’re still tart and tasty. She stoops to pick a handful. Beats endless energy bars, she jokes, and then she’s gone, trailing three seasons behind her. I envy her the cloister of her single-minded mission, Canada still weeks ahead. I’m tempted to follow her on the long haul north.

But the climbing trail soon parts ways with the PCT, dropping down the west side of the ridge to skirt the cliffs beneath Cathedral Rock. It’s narrow in places, crisscrossed with avalanche gullies shooting down from the cliffs above. We pass the first one mindlessly, moving between islands of Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir as we go. I’m just about to step out of the shade into vertical daylight again when I hear it—the sudden crack of displaced rock—chased by a slurry of loose gravel. It whisks on by just steps ahead of me, spilling into the emptiness downslope. If I hadn’t heard it first, feet frozen in place, I might be loose gravel myself. Whoa, I stammer. Did you see that? Bullet dodged. Dan corrects me: more like buck shot in search of a deer.

Another mile or so up the trail we reach Peggy’s Pond. It turns out frost hasn’t killed off all the mosquitoes yet. We set up basecamp, and, after a quick lunch, start up the steep heather meadows of the east shoulder. Oddly enough, we have Peggy’s Pond, and the climbing route, to ourselves—we’d heard the route was popular—but this is our first time here, so none of us thinks too much about it. Heather meadows give way to narrow, rocky ridges. Noa leads with a brisk pace, the rest of us straining to keep up. One by one we step lightly through a tight spot high on the ridge wide enough for a single foot. Beyond this adrenaline passage, I stop to take in the broad valley below now fully in view. Straight down, there’s Spade Lake and Venus Lake, languid bowls of cobalt blue sparkling in glacier-polished granite—water and rock one pulse tuned to different clocks.

We are relieved to discover the last traverse leading to the summit approach is snow-free. There’s a semi-permanent snowfield on the summit plateau, shriveled to its gaunt September weight, but that’s relatively flat and accommodating. This traverse across the steep divide between east and west summits would be treacherous in icy conditions. Still, we proceed with care. There’s no danger of rockslide from above, but plenty to initiate below, and yourself with it. I flush a brace of rosy-crowned gray finches from an overhang. They are not the only ones feeling touch and go.

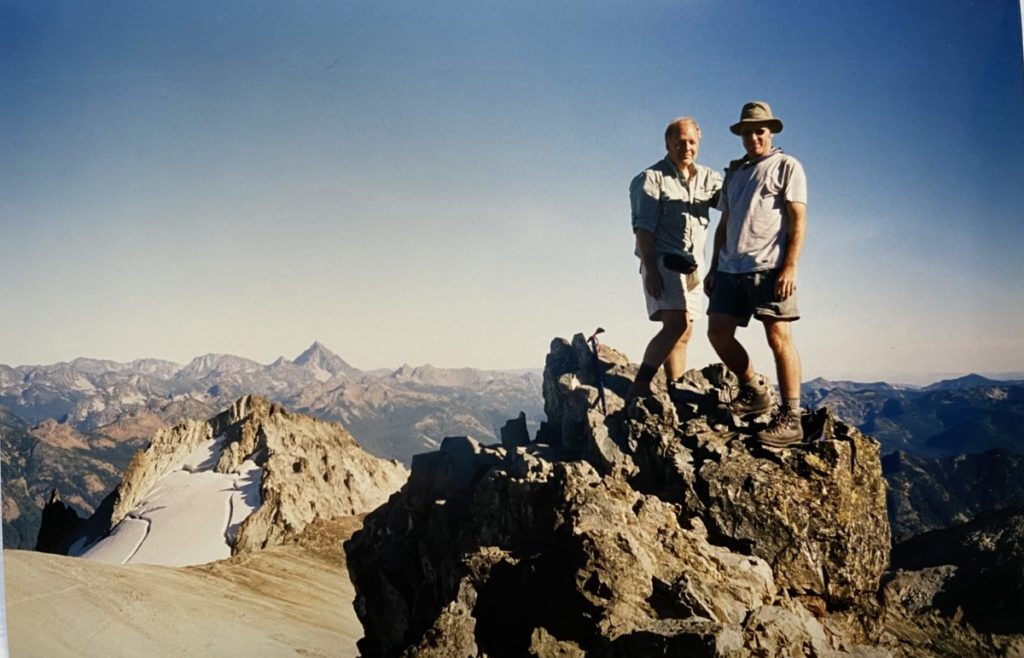

We reach the base of the west summit at 4:00 pm, about three hours from camp. Noa, exhausted by the pace she set, decides she’s had enough. She opts to linger on the ridge below, and Seth stays behind with her, the two of them feasting on trail mix and tracing sundial shadows in the snow. I scramble up first, a solitary tinhorn on the roof of the world. Dan snaps a backlit photo—he’s got the only camera after all—then scrambles up to join me, followed soon after by a resurgent Seth. The three of us conduct a brief renaming ceremony. Screw that old Civil War lieutenant, this is now Mt. Dan Lamberton. There’s no one else around to dispute the record.

Down at the base of the Lynch Glacier, Pea Soup Lake glistens like a gemstone embedded in gritted teeth—catch basin for the ice retracting all too quickly. Farther off, northeast in the Okanogan, we notice two distinct plumes—forest fires billowing brown and bending in the jet stream east. Two ravens circle the east summit, seeming to keep an eye on us. The sky is otherwise quiet and clear.

No time to linger. Shadows lengthen by the minute. We need to get back down through the tricky parts before the light fades. Back at Peggy’s Pond, flush with success, we build a small bonfire. Dan sings a camp song—in yet another life he was an opera tenor. On a log, Noa finds my ultralight pocket Wordsworth, flips through it until she finds what she’s looking for: A slumber did my spirit seal / I had no human fears . . . We curl up to sleep the heavy sleep of climbers, rolled round in rocks and stones and trees.

Hiking out the next day we are in high spirits. Andesitic Cathedral Rock changes like a chameleon in the morning light, shedding layers of rose and gold. I’m more reluctant than usual to leave this rarified place, taking every delay offered by bird or plant nagging me for identification. As a group we are loose and agile, stretching the bonds of camaraderie in our solitary musings along the lengthy trail, leapfrogging past viewpoints, each of us leading in turn, luxuriating in the downhill stroll.

Past Squaw Lake, on the last stretch, we meet a man on horseback coming up the trail—the first company we have seen since we set out. He’s leading a mule laden with saddlebags. Hunter, no doubt, putting in for the the high hunt. We step aside to let this horse and mule team pass. But he stops as he draws near, consternation etched into his brow.

“How long you folks been back here?”

“Three days,” I answer. “Beautiful weather.”

“Oh, so you haven’t heard the news.”

“What news?”

“Hijackers ran two passenger jets into the World Trade Center—New York City. The towers are down, completely destroyed. Thousands dead. Another one hit the Pentagon. All flights grounded across the nation. We’re at DefCon 5.”

“Def Con 5?” I repeat. The words shock my ears, don’t quite enter sense. I glance at Dan. He has a stricken look on his face—the same one I must be wearing. Towers down? Is this exaggeration?

“Are we at war?” Dan asks, his voice calm and measured, like a doctor sizing up a rattled patient.

“Best be ready,” the hunter continues. “Maybe you ought to stay back here.” Suddenly the rifle strapped to his back seems ominous. He sits there half a minute longer like some horseman of the apocalypse, then kicks his mount into gear. We watch him disappear into the shadows, unable to move ourselves, rooted to the ground in disbelief. What kind of world awaits us at the end of the trail?

Insouciance shattered, we press on quickly. Noa is particularly distraught, recalling an aunt who works in one of the Towers. We can’t get home fast enough. Soon another party approaches, climbers packing ropes and axes. You won’t need those, I offer, lightly. The route is clear. And: is it true what the horseman says?

In the parking lot there are few cars—far fewer than there might be on a sunny summer day. Beside one SUV, someone has left a newspaper on the ground. It’s today’s Seattle Post-Intelligencer—Wednesday, September 12, 2001. We huddle around the first photographic evidence of the attack. Smoke, fire, a close-up of the north tower in the first awful seizure of collapse. It begins to sink in. We’ve just lived a Rip Van Winkle moment—the world has changed irrevocably in our absence.

We hug each other—camaraderie cinched tight again by horror—then hurry down the pitted road on our separate ways home. As I’m driving over the Cascade crest at Snoqualmie Pass, I think of the thru hiker we met yesterday. How long until the terrible news reaches her? There must be hundreds if not thousands like her, still walking the unfallen trail.

In the apartment I find my roommate, Counsel, hovering by the television—a dark look hanging on her face. “When did you find out?” she asks.

“Just a few hours ago. By Pony Express.”

“I saw it happen. As it happened. The second tower. The whole world saw it in real time.”

A day behind the fever pitch of the planet, I’m stuck in lag time, grappling with disbelief. The 24-hour news cycle is a rabid machine. It seems an eternity has lapsed in my absence. I sit down to take in the news myself, absorbing for the first time the incredible video footage—smoke pouring from the north tower, then, fifteen stunned minutes later, the second plane plunging into gossamer steel.

It’s shocking enough in retrospect. The brazenness of the attack, turning a passenger plane into a missile—not one plane but four—seeing or trying to imagine hundreds of specific lives shattered on impact, all those thousands who couldn’t escape the towers, or decided to jump, taking fate into their own hands . . . Whatever tranquility or joy had filled my heart on the trail to Mt. Daniel sits frozen now in suspended animation. I can’t tear myself away from the screen.

We both have friends in New York. Counsel reports she had a hard time getting through at first but has since learned her friends are safe. I hadn’t thought that part through until now. I pick up the phone to begin those overdue calls to family and friends back east.

I reach my mother first, in South Jersey. Like everyone else, she has been glued to the TV. Her voice is solemn, laced with alarm. How are you, she asks, the note of motherly concern unmistakable. You were where? It seems no one we know is directly affected, but the ripple of connection to more distant relatives in the northern part of the state—those who might work in Manhattan or nearby—is not yet fully discovered.

My dad had grown up in Northvale, NJ. As Mom speaks, I recall the visits we’d pay to his relatives on weekends or holidays. Driving up the NJ Turnpike, the sight of the Twin Towers meant we were almost there, we’d entered another world. At the time, in the mid-70s, they were the tallest buildings on the planet. As a middle school kid from flat South Jersey, I could say after my first incredible visit that the World Trade Center was the highest I had ever climbed.

Later that evening I am finally able to get through to my old college friend, Arielle, who lives near Central Park. She is tired, hoarse, her voice stained with grief. No one she knows was in the towers, but friends of friends have gone missing, and another has lost her father. Or so they assume. There is still hope the missing may turn up in some hospital across town. On local news channels people plead for word of missing relatives. The site itself—what they have begun to call Ground Zero—is a smoldering plume, the air downtown choked with dust and ash. Across the city, horror and uncertainty prevail.

The next day, little else to do, I go walking around my hilltop neighborhood. I need to get away from the TV. Planes remain grounded, skyscrapers evacuated all across the country—no one is sure if the attacks are finished, if more might be coming. Here in Seattle, there are flags draped from nearly every porch. In some windows I see candles. Those who pass me nod with quiet affirmation. Even in this city, where strangers are notoriously aloof, the feeling of universal camaraderie is palpable. Words seem wholly inadequate, but the collective bond is clear. The news is difficult to watch, though it plays on a perpetual loop. Might as well watch a candle for all the light it sheds.

Two days later I wake early. Gray fills the window like a developing photograph, or a TV screen drained to static, nothing in the picture but void. I’m thinking about my camera. The weather has been unusually good since I climbed Mt. Pugh a week earlier. If I left it where I think I’ve left it, there’s every chance it could be retrieved intact. Suddenly this morning it seems important to try. So much has changed in week. But stranded in a mountain meadow, there’s a treasure box of images from a previous era. The anthropologist in me clambers out of bed.

Driving north, I mull my chances. Whether I find the camera or not, I return to Da Klagwats with a purpose. The trailhead sits at 1900 ft, Lake Metan at 3200 ft, and Stujack Pass at 5750 ft.—beyond which, maybe another 100 feet or so, sits Pentax Point (I trust). By comparison, the North Tower rose 1368 ft., the South Tower a little less at 1362 ft. I would climb those heights that had been toppled, honor the dead and missing in pilgrimage, turning time into its own walking memorial. Contour and convulsion, layer and upheaval, erosion and endurance—the language of mountains is the only lexicon that makes any sense.

It’s mid-morning when I set out. The first mile crawls by, familiar and strange. At a creek crossing I stop. On the other side I spot a brown creeper winding its way up the fuzzy braid of a western redcedar, one of few such trees in this vicinity that escaped the loggers a century ago. The creeper is a climbing bird. It scans the bark for insects, picking and grooming a ragged line up the trunk, dropping down to a neighboring giant to start the hunt again.

On I go. Mt. Pugh soars steeply above Lake Metan, its summit slopes reflected in the murky lake. I stop briefly to refill my water bottle, having now ascended 1300 feet. One tower completed, the other looms like an avalanche stilled. The lake disappears at the next turn in the trail. I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster— Bishop’s poem come back to me, right where I left it, every line haunted by irrevocable loss.

The trail brushes up against the lower end of the avalanche meadow. The final stretch in forest zig zags up a rib buttressing that knife-edge ridge a thousand feet above. Just as I’m about to leave the woods behind for open slopes, a chickadee flutters across the path, followed by another. And another. Soon I am engulfed in a cloud of black-capped chickadees, all clamoring at the same moment, I the object of, the center of their chatter. What can I do but stand there, overcome with amazement bordering on revelation, feeling like a latter-day Franciscan, only in reverse? In this forest the birds do the preaching. Our task is to listen and be still.

Even losing you . . . I find the Pentax K-1000 on the far end of my summertime nap, beside the log on which I propped my head, wedged in a patch of heather. All around me meadows simmer in technicolor splendor—red and white heather, huckleberry, mountain ash. Inside the camera, a scroll of landforms ravels in the dark. Like some imperceptible dimension curled up in a garden hose, the film canister layers exposure on exposure, a palimpsest of images holding time in place, lost and found.

Four exposures remain. I take a picture of the spot where the camera sat. It seems only fair that that the Pentax should record its namesake point, the site of abandonment, the locus of regain. For the second shot, I widen the lens, aiming through the notch of Stujack Pass at the trail that brought me here, twice—once in ambition, once in reflection—taking in the river-ribboned valley and all its gusty chickadees.

I take the last two shots in quick succession: zooming the lens the full 50 mm, I frame a piece of sky just above the summit block, the peak itself poking into the frame like the tip of an iceberg—f/22, shutter speed 120, black and blue. For the final frame I turn the speed dial to infinity, hold the shutter open to let the sky wash out to nothingness, overexposed.

On October 4, 2001, Carlene Mendieta lands her Avro Avian at Westchester County Airport in White Plains, NY. She is a week behind schedule—but still well ahead of history. On September 4, she had set out from the same airport—as near as possible to the airstrip from which Amelia Earhart launched her flight across America in 1928. Mendieta’s goal: recreate Earhart’s historic flight in a taildragger biplane—built the same year, in the same UK factory, as the one Earhart flew.

Earhart’s flight took two months, hop skip jumping from state to state, airstrip to farm field, even landing on Main Street in Hobbs, NM, when she lost her way. Mendieta had planned to cover the exact same trajectory in about three weeks. Meticulous in the details of reenactment, Mendieta flies the open cockpit Avian in twill helmet and googles, jodhpurs and leather boots. She even sports the Earhart bob. But many of the fields in which Earhart landed are now strip malls or housing tracts. The Westchester polo grounds Earhart had used to launch her journey is now the driving range of the Fairview Country Club. Mimesis has its limits.

On September 11, all airspace in the US was shut down. It remained that way for the next eight days. Stuck in Hobbs, NM, herself, Mendieta grew more determined to complete the flight. She had begun her journey to honor Earhart’s pioneering feminism—now she was an emissary of the airspace itself, the representative of a different era when a friendly biplane could drop out of the sky and land safely in your own backyard.

Some events are so powerful they are said to change the course of history. When I see the photos of Mendieta’s cockpit salute at the airport in Westchester, when I reread Bishop’s “One Art” with my students, I see a different kind of historical reckoning—one laced with solo courage and quiet dignity, one that binds us through ecologies of loss and regeneration to the places we love. It’s evident / the art of losing’s not too hard to master, Bishop writes (or, perhaps, rights it, like a ship) adding a note of humility in closing—almost a retraction when stacked against her previous declaratives. She turns her one art into a reciprocal pact between act and artifact, faithful to dis-appearance, all that we can never see or know.

Among the images I rescued from a mountainside, I picture the Forest Service Supervisor who flew over the summit of Mt. Pugh in August 1927 to deliver The Seattle Post-Intelligencer to the lookout on duty, dropping his mail bundle 50 feet from the cabin door.

In another frame I see Venus Williams shaking hands with her sister, victory and loss two sides of the same long volley.

And then I see Bill, walking out of the ocean, young again, a lanky boy ready to climb.

—

Kevin Craft directs the Written Arts Program at Everett Community College. His work has appeared in The Stranger, City Arts, Elevation Outdoors, and other journals. He is a Contributing Editor to Poetry Northwest, and Founding Editor of Poetry NW Editions.