bill bissett at eighty

by Jim Johnstone | Contributing Writer

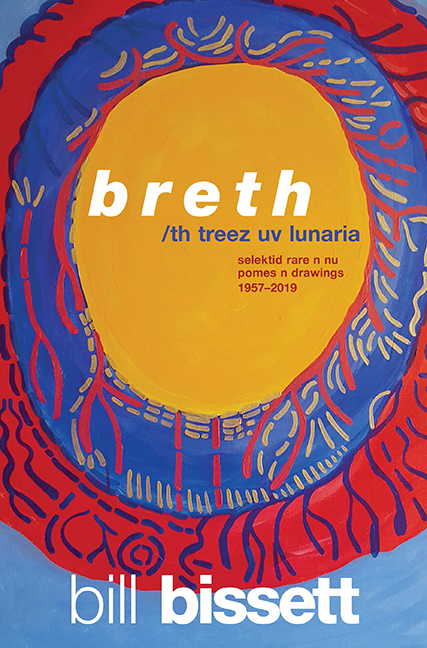

breth / th treez uv lunaria

bill bissett

Talonbooks, 2019

There have been many superlatives thrown around to describe bill bissett over the course of his career. He’s been called a shaman, a visionary, a secular prophet, a countercultural icon, a one-man civilization—all descriptions that address the ineffability of bissett’s poetics, yet fail to describe him in concrete terms as an artist. In large part, this stems from the poet’s mythology as one of the founding members of Canada’s avant-garde, a hippie turned jack-of-all-forms who’s become a mainstay in galleries and on stages across North America for almost sixty years. It’s hard to pinpoint when bissett crossed the line from man into myth, but he’s added a significant amount of fuel to the fire himself with invented biographical details and unearthly origin stories (the most common being that he arrived “on th first shuttul uv childrn from lunaria 2 erth” instead of being born in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1939). bissett’s effervescent performances make such claims seem, if not possible, then at least rooted in the spirit of his otherness.

The eighty-year-old bissett’s recently published 529-page volume of new and selected poems, breth / th treez uv lunaria, brings his craftsmanship to the fore and emphasizes the diversity and range of his verse. Crack breth, and you’ll find lyric meditations, typewriter art, songs, concrete poems, and political narratives all sharing space, sometimes even the same page. In terms of variety alone, the collection is an unqualified success. Showcasing work that’s long been out of print, breth gives readers a window into the various poetic modes bissett has mastered, mixing and remixing material from his earliest books up to present day trade collections. Such a chronology might sound daunting, especially considering breth’s gargantuan breadth, but it turns out that the book reads like a collection of greatest hits (bissett has a lot of them) balanced with deep cuts from bissett’s restless, often genre-defying, canon.

For those unfamiliar with bissett, the first thing you’ll notice on reading his poems is his use of phonetic orthography. This approach creates an initial make-or-break moment for first-time readers. In theory, phonetic spelling (along with a lack of punctuation) can be used to destabilize traditional linguistic devices, allowing words to merge, recombine, and break down into their base morphological units. bissett’s application of this practise has been idiosyncratic, but for the most part he’s used it to explore the non-hierarchic possibilities of language. On one end of the spectrum, his visual work pushes toward what he’s called the “molecular dissolv”—a space where words move past conventional meaning into their concrete, lettered forms. This is a juncture where language meets fine art, something that often blurs in breth, particularly in bissett’s hand-drawn, pictogram-like material. At the other end of the spectrum, bissett’s narrative poems are malleable, freeform trips into the poet’s subconscious, stripped of syntax in a way that encourages interpretation, and multiple (or even conflicting) meanings.

Free of traditional logic, the metaphorical leaps that bissett makes charge his poems with mystery. Take “th breath,” the would-be title poem of the collection (“would-be” because here bissett uses the conventional spelling of “breath” instead of the “breth” of the book’s title). In this poem, bissett writes that breathing “is th same as th eyee / opening” and

all th worlds of green snow fold

inside th heart

and th rhythm is th skull

The first thing to notice here is the double “e” that ends the word “eyee.” It’s as if bissett is encouraging the word “eye” to open, slowing his metaphorical reveal. All lens and lashes, the “eyee” widens to observe “worlds of green snow,” a kind of seasonal duality that conjures the beauty of winter and summer before bissett returns to the body (“th heart,” “th skull”) again. Originally published in 1972, “the breath” was the first poem in Beyond Even Faithful Legends (Talonbooks, 1980), bissett’s last major volume of selected poetry. Since that time the poet’s phonetic spelling has become even more unruly, and his decision to leave most of the older work in breth unaltered creates a kind of timestamp. Interestingly, the orthographic inconsistencies in bissett’s work create potential new building blocks of meaning—for example, the way the “a” in “breath” has gone missing in later iterations might make it seem as if the letter has been lost on an exhale. This compression also brings “breth” closer to “berth,” the human chest closer to the hull of a ship.

Spelling quirks and all, breth’s consistency is startling, especially considering the decades it spans. Reading the oldest piece in the book, an “untituld pome,” composed when bissett was a teenager, it’s tempting to assume that his poetics were fully formed when he arrived in Vancouver in the late 1950s. But those years were a time of apprenticeship for him (writing alongside poets like Milton Acorn, Judith Copithorne, and bpNichol), a time that saw the establishment of blewointment press, a book publishing company that grew out of blewointment, a literary periodical founded by bissett (and noted for its lowercase, phonetic spellings and for its hand-decorated and mixed-media covers and inserts). The press was dedicated to printing work that was “vizual non linear n not cumming from aneewhere n mostlee left wing politikalee.”

Still, the Beats in particular were influences, and bissett’s work displays some of the ecstatic and political hallmarks of poets like Phillip Whalen and Richard Brautigan. In a 1968 issue of The Paris Review, Jack Kerouac called bissett “the greatest living poet today”—despite the fact that nearly all his work was either mimeographed or photocopied at the time, and difficult to obtain.

One of bissett’s earliest trade projects was awake in th red desert (released as both a book and record by Talonbooks in 1968), which featured a meditation on national identity titled “Th Canadian.” Reprinted early in breth, “Th Canadian” is prescient, foreshadowing Canada’s ongoing colonial backlash. In it, bissett writes that he

did en

vision th society of fact in Canada

as a train, its peopuls classd, & sub-

classd, according to th rank they owned, or,

who they cud claim owned them, its

peopuls cut off from each othr by

such coach cars & compartments.

Contrary to the government-directed nation-building projects of the time—the Canada Council of the Arts was established in 1957, and the current Canadian flag adopted in 1965—“Th Canadian” rails against settler notions of hegemony and freedom. Early in the poem, bissett acknowledges the discord between Indigenous peoples and those who colonized (and continue to colonize) the land; he uses the country’s centennial as the poem’s occasion. In the poet’s imagination, the train he posits as a country cuts citizens off from one another in coach cars and compartments. Soon, “darkness, / fortif[ies] th condition, keeping each in place, / lest they overcome fear & th structure toppul.” bissett’s vision is unnerving; it sees prisoners transported across the country by rail, hinting at the Japanese-Canadian internment during the Second World War. The poem also gestures toward the poet’s own clashes with the law; bissett did jail time in Powell River, Vancouver, and Burnaby, British Columbia.

With respect to bissett’s creative spirit, Toronto-based critic Mike Doherty once called him a “devotee of both / and.” While “Th Canadian” doesn’t appear on the recorded version of awake in th red desert, many of the poems on that record have become part of what amounts to bissett’s sonic signature. These include “anodetodalevy” and “my mouths on fire,” both of which are represented in breth, and which use repetition as a means of creating mantra-like soundscapes. This technique is strikingly mnemonic in “anodetodalevy,” a tribute that predates the Cleveland poet d.a. levy’s death in 1968. Using various permutations of the line “this is an ode to d a levy,” bissett riffs on levy and “his gentul beard” while the spacing between letters on the page expands and contracts to regulate the speed at which the poem is read. In this sense, bissett’s written approach to sound poetry is, as Chris Jennings has stated, characteristic of musical notation. It’s also flexible, something that’s evident in the iambic chant of “i dreem uv northern skies” in “slow slow rabbit song,” which allows the poet to adjust the rhythmic and tonal patterns of repeated passages to vary the emotional tone of the poem.

Online resources are helpful for those seeking an immersive bissett experience. Many of the poet’s performances can be found on the web, including an extraordinary interview with Phyllis Webb and bpNichol that was originally broadcast on CBC television in 1967. During the sit-down (at around the four-minute mark), bissett performs “HOW WE USE OUR LUNGS 4 LOVE,” a high-water mark in his early sound work, breaking into a percussive meter that at points resembles song. Ostensibly a love letter to language itself, “HOW WE USE OUR LUNGS 4 LOVE” is disjointed and often surreal, as when bissett describes “th ceiling th horse / came out uv in disguise as a blu kettul drum,” or “when th wheel combines 2 open th / mirage.” After a page and a half, the poem breaks down, monosyllabically lurching into a sequence that forgoes predictable reading conventions. At that point, it branches vertically, concluding:

swamp swing beetles nest slides blankets

summr sand inside O

door willow this

stain under beach

before him is

hang she cool

after him in

she saw she my

him him mouth

swing she she

hyena him him

thrill she sang

rope him under

softer n she him

pussy him away

n rose she in

over him daisy

pull up

in

Though narrative sense seems to have been abandoned in this passage, bissett moves through a litany of words that make sinister meaning: “hang,” “swing,” and “rope” follow “willow,” forming an ominous strand. The poem reaches its climax by alternating between pronouns (“she” and “him”) as if it were cutting back and forth between protagonists holding hands and spinning. Disorienting, and laid out to suggest a pair of lungs, the passage is a great example of the ways in which bissett leaves his work open for interpretation. For example, the reader could choose to see the vertical branches introduced here as bronchioles, or as rope hanging from a willow tree. There are several instances in breth where the poet encourages readers to interpret his work as they see fit, saying so directly in “we ar almost ther,” when he asks readers to “make yr own variaysyuns n / sustaining lines or parts uv.”

Immersed in breth, one would be hard pressed not to succumb to the sensation described in “dragon fly,” when the poet writes that “all / air waves at once sound in [the] ear.” Throughout the poem those waves are shaped by the words on the page, running to the margins before taking the shape of a mountain—and then a water droplet that reads:

side orders

mahogony

macha macha ling

all down th waterfall

moss house moss stone

moss love moss light

moss water moss lifting

moss delight moss smell

moss webs moss beam moss

see th spider spinning moss

moss lake th rain falling th moss

lake smiling on yu moss dust in

yr air moss loving fingers

lifting moss nd th lady

moss on th path weaves

all yr lives reveal

Visual and textual elements frequently coalesce in bissett’s work, and here they combine to represent a bead of sweat on a radiator. Moss lines the left-hand side of the water droplet as if it were transparent, revealing the natural world within. There bissett punctuates the poem with images from everyday life—a “house,” “stone,” a “spider spinning” its web. As “dragon fly” continues, its words slide down the page, mimicking the poet’s distorted consciousness. bissett also makes it a point to emphasize the unreliability of language when he writes “forget th dialectick th dialectick forgot / yu,” urging readers to remain open to associative movement.

bissett’s work is weakest at its most traditional. This is true of his more recent political poems, which can be one-dimensional and feature paint-by-numbers provocations. In breth this applies to work like “war sucks,” “billyuns uv tons uv plastic bottuls,” and “evree brain is diffrent,” each of which offer reductive takes that exhort without the artifice needed to win new political converts. In general, bissett’s political poems are better in comic bursts, as in “watching broadcast nus,” reprinted here in full:

i see th salmon talks will

resume on monday

well thank god at leest th

salmon ar talking

Part of a series of salmon poems that spans multiple books, “watching broadcast nus” illustrates how the poet’s humor adds levity to quixotic material. This kind of wit is evident elsewhere in breth, notably in “it used to be,” when bissett posits that “yu cud buy a newspaper n sum / toilet papr 4 a dollar fiftee // now yu cant // yu have 2 make a chois.” Spelling “used” in a way that mimics the international shorthand for American currency (USD), he criticises capitalism with cleverness and humor. Moments like these are sprinkled throughout bissett’s narrative work, balancing his earnest, but less convincing material.

In its versatility and scope, breth represents a life lived in, and through, poetry. At age eighty, bissett continues to produce work at the pace of a much younger artist, and despite the fact that new poems aren’t rare, they’re a continued act of will. As a writer who’s made a career out of challenging the literary establishment, he’s faced constant pushback from the orthodoxy. It’s been some time since Conservative minister Bob Wenman called bissett’s work “disgusting and pornographic” in Canadian Parliament, but the poet still faces an uphill battle as a living legend who ekes out a living as a poet well past retirement age. There are few writers who have managed to sustain a more distinct—or vanguard—poetic practice than bill bissett. As such, he’s a necessary addition to the growing list of Canadians who have authored volumes of selected poetry in the 21stcentury. Not as definitive as the compendiums by other Vancouver-based contemporaries in Talonbooks’ collected series (Fred Wah’s Scree and Daphne Marlatt’s Intertidal come to mind), breth nonetheless goes a long way in untangling bissett the writer from bissett the legend of otherworldly provenance. In fact, the most surprising aspect of breth is just how human the poet’s work feels in today’s literary climate, as if contemporary practitioners are just beginning to catch up with bissett’s hybrid approach to verse. This is a welcome development, and there’s more to come. bissett is currently at work compiling a companion volume to breth that will bring more of his out-of-print and hard-to-find material to the fore. As bissett might say with his trademark enthusiasm: “raging, xcellent!”

—

Jim Johnstone is a Toronto-based poet, editor, and critic. His reviews have been published in magazines like Maisonneuve, The Rumpus, and Poetry, where he won the Editor’s Prize for Book Reviewing in 2016. Currently, Johnstone curates the Anstruther Books imprint at Palimpsest Press. His most recent book is The Next Wave: An Anthology of 21st Century Canadian Poetry.