Absence as a Silhouette: On Writing Becoming Ribbons

by Amber Adams | Contributing Writer

I wrote the first real poem about my ex-husband a month after his memorial.

We’d graduated from the same high school in the tender years just after the attacks on the World Trade Center. We both watched the planes crash on televisions wheeled into the cafeteria. The country was outraged, and our President had sworn to go after terrorists wherever they may be hiding. Toby Kieth’s “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue (The Angry American)” was blaring from every radio, and young boys across the country swore to terrorists living on the other side of the world, “You’ll be sorry that you messed with the U.S. of A., ’cause we’ll put a boot in your ass, it’s the American way.” Yellow ribbons were tied to trees. Magnets were made. There was a boom on American flags.

Amidst this backdrop of a country flexing its military force, my ex-husband and I began our relationship. We were an unlikely couple. He was my older brother’s best friend, and in the social sorting of high school cliques he had come out on top: one of the populars, a charmer who could get away with trouble-making and middling grades, a swim team all-star, whereas I was a smattering of emo, goth, and punk, smoking cigarettes outside the drug-free zone. I spent my time journaling my thoughts in grungy diners, collaging song lyrics and poems like Ginsburg’s Howl.

In the push to come up with post-high school plans we both ended up enlisting in the military—a commitment that made us harder and prouder than our merely college-bound peers. Our commitments to our respective branches-of-service underpinned our commitment to each other. Like many military relationships (or any first big-love, long-distance relationships, for that matter) we were propelled by a hyper-drive urgency. We were engaged after a month of dating, married in a rushed courthouse wedding a year and a half later. All the while, the requirements of active duty constricted the thorny growth of our late teens and early twenties. Our relationship consisted of letters scribbled on cots under wool military blankets, bursts of intimacy on leave, and long drives between Colorado and California. His deployments always loomed, upcoming, or just completed. He used to joke that he was in Iraq so often they should grant him honorary citizenship.

On his fourth tour, my ex-husband was hit by an improvised explosive device. Shrapnel tore through his side. Tattoos burned from his arms. In that same explosion, he lost his best friend and comrade. He became someone different, and our relationship, by now barely hobbling along from so much separation, starts and stops and email reconciliations, officially ended. He was medically retired from the Marine Corps. In the years after this event, he remarried and had a daughter.

Less than five years after his injury, he died by suicide. At the memorial service, I was handed a pamphlet with an abbreviated biography: his birth date, his service record, a list of military awards. I sat through a photo reel that included photographs I had taken—from the reservoir where my family weekended, from goodbyes before his battalion left for his third deployment, even one I snapped of him and his best friend who died. But I always seemed to be cropped outside the carefully framed life being presented.

For weeks I carried that pamphlet with me, reading it again and again. What I couldn’t reconcile about the document was how his life had been compacted into a list of military acronyms, decorations, and deployments. There was a photograph of him shaking President George W. Bush’s hand, another of him in full battle rattle from his second deployment, but none of him playing one of the instruments he could just pick up by ear, or horsing around, or camping, or any of the things that brought him boyish joy. In every picture he was hidden behind a pair of combat sunglasses.

I began writing poems to fill in the gaps, showing the love we shared, the effect of enlistments on our marriage, the depths of his suffering, and the way that his service, while it made him proud, also traumatized him. I wrote of our letters that danced around his grief with jingoistic beliefs. And finally, I wrote about the pain of his suicide. I couldn’t believe how young we were, how responsible we felt for upholding this idea of American might. We both were deeply entrenched in military ideologies and the belief that we were serving our country. So it felt like a radical act to reclaim my own history, to tell the story as I knew it, in the fragmented language of my memory.

But still, there was this funeral pamphlet. A document that plagued me with its half-truth artifice. Originally I’d included the whole document in my manuscript, spliced by my poems, and titled the collection Not Written In Funeral Pamphlets. But something was off. When I read the pamphlet excerpts, I couldn’t tell if I was letting them frame my words, or worse, giving credence to those words, which felt like too much power. The text couldn’t exist in its current form. It needed to be altered in the same way it had altered out the personhood of my ex-husband. Initially I played with turning the pamphlet into a blackout poem to see if I could demilitarize it. This left me with a page of blacked out text. I tried it again, this time trying to reveal something truer with the absences—either making the erasure of selfhood more prominent, or personalizing the international scope of the war.

It’s widely acknowledged that the act of othering and tactical dehumanizing occurs throughout military training. Think of the desensitization that occurs when soldiers shoot practice targets in the shape of humans. Or the cadences sung to mark marching time: “A yellow bird with a yellow bill, sat up upon my windowsill, I lured him in with a piece of bread, and then I smashed his yellow head…” Each of these contribute to a culture where violence is not only normalized but valorized. Notice how neither of these examples deal directly with the expected barbarism of the job. The dehumanizing happens in the space of metaphor and euphemism. Think of the “enhanced interrogation techniques” of war prisoners that we now know is a polite way of saying, “We tortured some folks” (Obama, 2014). The military’s use of language often belies the true extent of destruction.

The danger in letting violence exist in metaphor is that it leaves open the question of how much violence is, in fact, occurring, and if it is legal. The public becomes shocked and outraged when photos and stories surface which contradict the sanitized versions presented on the news. The abuse and torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib is just one in a long list of examples. While there are many contributing factors to the war happening outside the purview of citizens (and reasons why war industry would like to keep it so), one way it maintains this distance is through the use of obfuscating language and state authorized censorship. The poet Solmaz Sharif writes in an essay about erasure that the “proliferation of erasure as a poetic tactic in the United States is happening alongside the proliferation of our awareness of it as a state tactic.” While she writes more directly about the censorship of prisoners in Guantanamo Bay (which the State refers to as “detainees”), we must acknowledge the extent of that erasure not simply as censorship, but also as a removal of humanity and legal rights.

The State uses such distancing language not only to refer to opposing forces of the United States, it extends to American soldiers as well. “Support the troops” is a tagline for politicians lacking clarity of what “support” actually means for/in terms of the devastating backlog of medical and psychological services to care for these service members after deployment. Under the Authorization to Use Military Force, troops have been deployed in over a dozen countries (Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Georgia, Yemen, Somalia, and Djibouti just to name a few) without Congressional oversight or regard for the strain of multiple deployments on the individual. Reservist and National Guardsmen, once thought of as standby soldiers, are now integrated into the active rotation of battalions deployed in the expansion of American occupation of sovereign countries. In the eyes of the State, a soldier is no longer a citizen, but a weapon of military intervention.

The problem is, there’s a cost to seeing soldiers as weapons. Weapons aren’t allowed to disagree with direct orders. Weapons aren’t allowed mental health breaks. Weapons don’t have children growing up in their absence. The 6,000+ veteran suicides per year are not just a product of combat-related trauma, but the result of a culture that discourages seeing oneself as a vulnerable and complex individual, that provides little to no resources to contextualize one’s relationship to their unique experience, that passes the burden of care off to overbooked physicians, that normalizes firearms, and that discards individuals if they can no longer fill their purpose. Viewing veteran suicide as a mental health issue and not a cost of war is a linguistic way to avoid culpability.

So where does poetry fit into this? What can poetry do in the face of dehumanization? Poetry cannot stop war, suicide, or even affect politics. Its power is in its ability to document what Carolyn Forché refers to as recit éclaté. In the foreword to Against Forgetting she writes “The French call this procedure recit éclaté—shattered, exploded or splintered narrative. The story cannot travel over the chasm of time and space. Violence has rendered it unspeakable.” It is up to poetry to hold these splintered narratives in their shattered form, so as not to dismiss the violence that created their fracturing. It is one of the few public spaces to document injury, to hold a mirror to the body politic’s illness.

Poetry is an art form for the gaps—the unsayable, the miscommunicated, the unsaid, the omission. Erasure poetics specifically is a form of dissent, and more specifically a dissent of eradication. It can serve to amplify the human redaction committed by the State and reclaim power through rejecting the dominant narrative. As our country, sometimes reluctantly, limps towards an ethos of equity, the need to find ways of slashing the dominant narrative becomes more pressing. Erasure poetics has, and can continue to create that wedge, that finger-hole into seeing a typographic absence as a silhouette of a person or entity that once was. In her seminal work, Zong!, M. NourbeSe Philip uses the redaction of English court proceedings to amplify the dehumanization and massacre of enslaved Africans on the slave ship, Zong. Of her use of erasure, Philip writes,

I murder the text, literally cut it into pieces, castrating verbs, suffocating adjectives, murdering nouns, throwing articles, prepositions, conjunctions overboard, jettisoning adverbs . . . and like some seer, sangoma, or prophet who, having sacrificed an animal for signs and portents of a new life, or simply life, reads the untold story that tells itself by not telling.

M. NourbeSe Philip, “End Notes” to Zong!

The violence inflicted on the African men, women, and children aboard the slave ship (the “cargo” as they are referred to in the report of Gregson v. Gilbert) is the violence the text itself endures—-and it comes out ragged. At times, the text is so broken that the only thing still there between Philip’s whiteout (not blackout) redactions is a single letter. The reader must reach across the page for word completion, sounding out as if relearning phonemes. I think of these letters as haunting wails, simply sounds of pain. Redaction, in this text, functions as a mirror for mutilation and murder, trying to cross over from the unsayable and bring some witness of horror without the manicured wash of legalese.

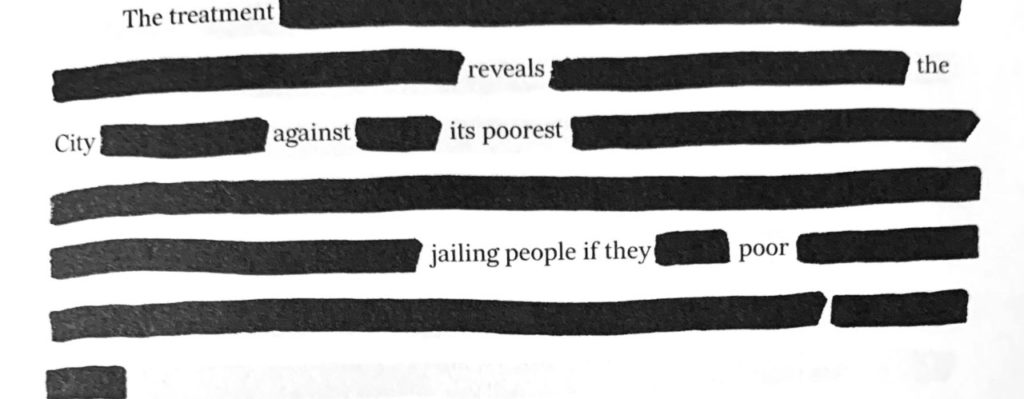

More recently, Reginald Dwayne Betts uses blackout in his collection, Felon, as he redacts motions filed by the Civil Rights Corps to challenge rulings that persecuted individuals struggling with poverty. In his poem “In Alabama,” the plaintiff, unable to pay a traffic ticket, is jailed and given the option to work off her debts at $25/day “scrubbing feces and blood from the jail floors.” Betts’s use of redaction highlights injustice while also making frank observations about what it means to be the target of an institution with the power to debase, strip freedoms, and enslave with impunity:

I think of how even a text that is working to correct systemic injustice, such as this one, is bound by the anesthetized and “civilized” language of the oppressors (the State). How redaction in this context attempts to say plainly what has happened—this person has been jailed for the crime of being poor. But it’s not enough to just say that; many people have said this or other variations of such sentiments. The taking away of voice, the marking out, and weaponizing the language of the State is the radical act.

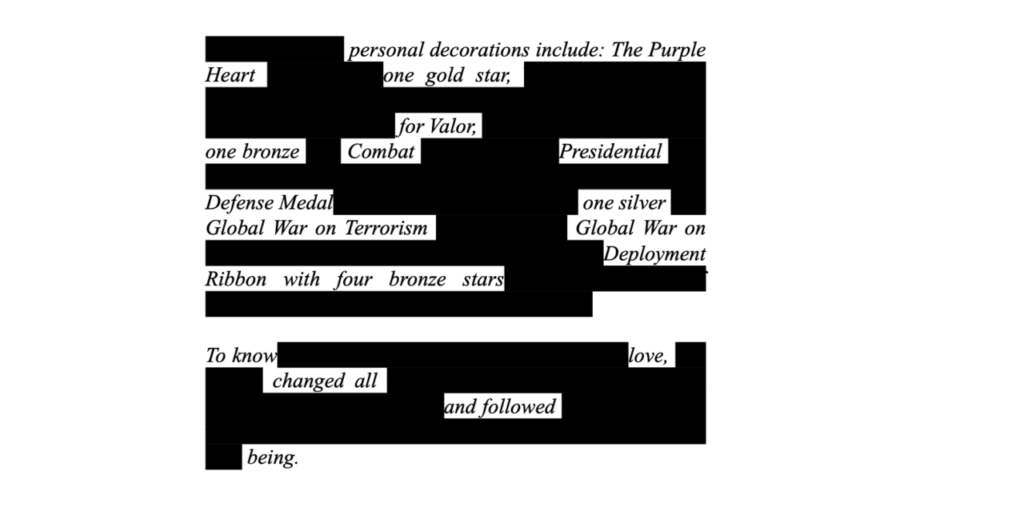

This is what I had in mind as I approached my own collection. I wanted to mark out as a way to not only re-humanize, but also as an act of holding the State accountable for veteran suicides. As Denise Levertov states, “There is no suicide in our time unrelated to history.” I wanted that history—the endless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the lack of personhood of soldiers, the absence of psychological care—to be evinced as I subtracted the hyper-militarized biography of the funeral pamphlet:

In this excerpt, I approached redaction two different ways. The original text began with a complete list of my ex-husband’s military decorations including the “stars” indicating the repeat of awards. As I read it, I thought of the Purple Heart as a bruised heart, I thought of the gold foil star stickers that we give to children for good behavior, I thought of the egotism of a President that would send our troops off to fight a war on terrorism. I thought of how I would like to wage a war on actions too: I would like to declare a Global War on Deployments. These were the ways I tried (in the spirit of M. NourbeSe Philip) to invade the text, weaponize it, strip its uniform, turn it on itself, and abandon it without the world of meaning it once belonged to. Also I wanted to underscore the cyclical and unending nature of rotational deployments through repetition of words like “global,” “war,” and “star.” While these words were inherent in the list, foregrounding their presence magnified the scope of responsibility, and brought a cadence to the text, creating an axis for the violence.

The second stanza presented a different lexicon. It was more in the spirit of perfunctory descriptions of a person that are often included in obituaries (“to know him was to love him,” “his smile was larger than life,” etc.). When approaching this text, I tried to use redaction as a way to move closer to a truth, from an observer into an embodied experience. Here I tried to be blunt (in the spirit of Reginald Dwayne Betts) in saying that this love changed us both and continued to change us long after the dissolution of our relationship. Redaction became a way for me to move from the political into the personal, and articulate my own splintered narrative—to mark the psychological violence inflicted and absence endured not just in his narrative but in mine.

As I wrote, I started to see my poems less as filling-in the biography in the funeral pamphlet, and more as a voice that has been brought to the edge of the speakable and still manages to say something. I changed the title of the collection to Becoming Ribbons, as it articulates both the physical injury and the accumulation of military accolades while the individual identity attenuates. I also started to see in the redacted text the shape of military ribbon stacks as they are worn on formal dress uniforms.

I can’t help think of my ex-husband at twenty-one, wearing his dress blues as we were married. At the time I thought he looked brave and handsome. Now I see his uniform as a symbol of the State—my marriage to the military instead of one man, his identity already being subsumed. How willing, how proud he was to put his individualism on the line for something greater. Is this self-erasure that comes with enlisting a precursor to veteran suicide? Or was his suicide a final reclamation of what had been taken, his autonomy, his eroded self? Or is this just me trying to make sense of the senseless?

The act of turning the pamphlet into erasure poems was a rebuke of the dehumanizing language that pervaded the document and stood as a synecdoche for the dehumanizing that occurs in military lexicon at large. The document’s absences had to be grappled with by the reader, who I realized would never see the pamphlet in its entirety; the thing they would have to bear witness to was this irreconcilable lacunae.

—

Amber Adams is a poet and counselor living in Longmont, Colorado. Her debut collection, Becoming Ribbons (Unicorn Press, 2022), was a finalist for the X.J. Kennedy Prize and semifinalist for the Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize. She received her MA in Literary Studies from the University of Denver, and her MA in Counseling from Regis University. Her work has appeared in Narrative, Witness Magazine, Birmingham Poetry Review, War Literature and the Arts Journal, Porter House Review and elsewhere. She served in the United States Army Reserves and completed one tour of duty under Operation Iraqi Freedom.