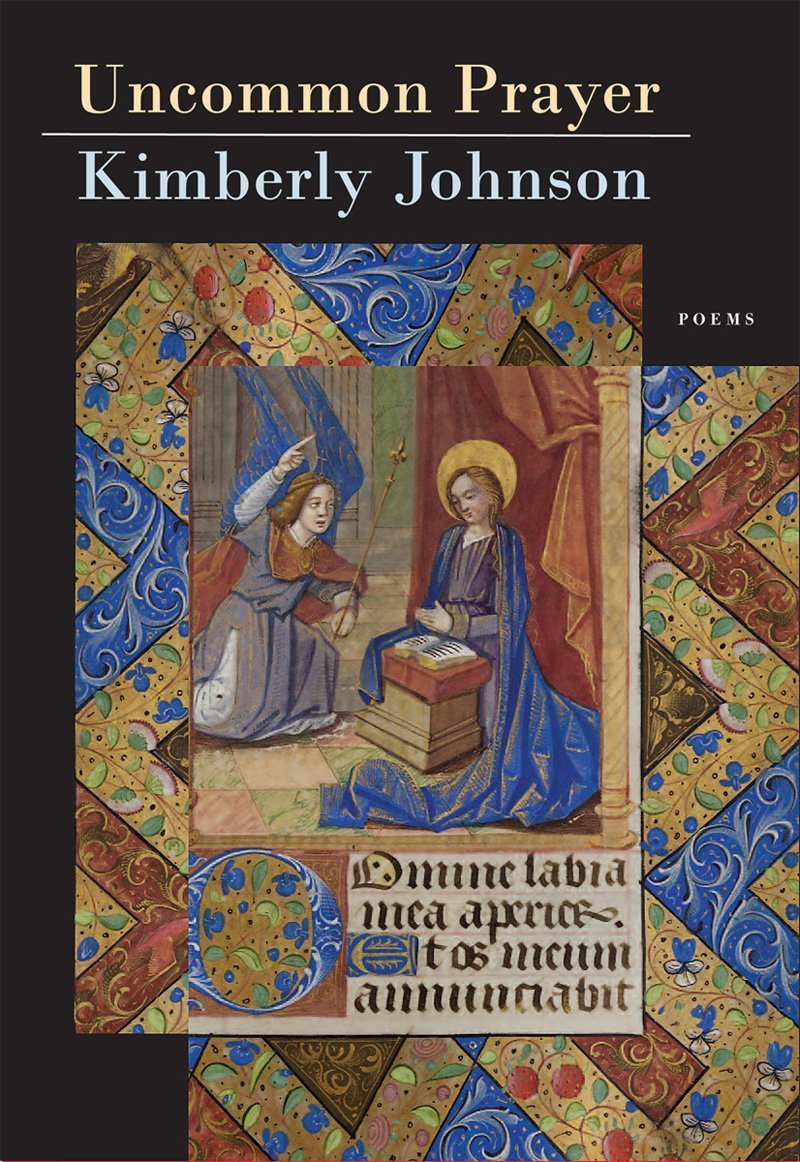

Emily Warn: “The Almost Wilderness – Remembering Denise Levertov”

May 16 is Denise Levertov Day in Seattle. For a listing of related events, including a choral setting of Levertov’s poem “Making Peace,” visit St. John’s Parish. I’m waiting for the kettle to boil in Denise’s kitchen. It’s mid-November and raining. Out the window, the branches of her unruly pear are outlined against the gray sky. At three-thirty it’s already dusk. I look across neighboring roofs and down to Lake Washington where I can barely distinguish lake water from the black forest rising behind it. I pour boiling water into Denise’s serviceable yellow tea pot wide enough to hold four cups, swirl it around the sides, and dump it into the sink. I put three tablespoons of English Breakfast tea into the pot, refill it with water, and steep until it is black and strong. I set it on a tray next to a sugar bowl, pitcher of milk and a plate of cookies, and carry it all into the living room where Denise is sitting on the couch. Brewing a perfect pot of tea was our …