Interview // as echoes, as ghosts: Paul Hlava Ceballos and Quenton Baker in Conversation

by Paul Hlava Ceballos | Contributing Writer

I saw Quenton read his work before the release of his first book, This Glittering Republic, and we became friends. In the following years, as we did readings together, we talked about the overlapping arcs of our research and writing; Quenton was working on erasures of a Senate document detailing the 1841 revolt aboard the slave ship Creole, and I was piecing together a collage of texts detailing the history of bananas in the Americas.

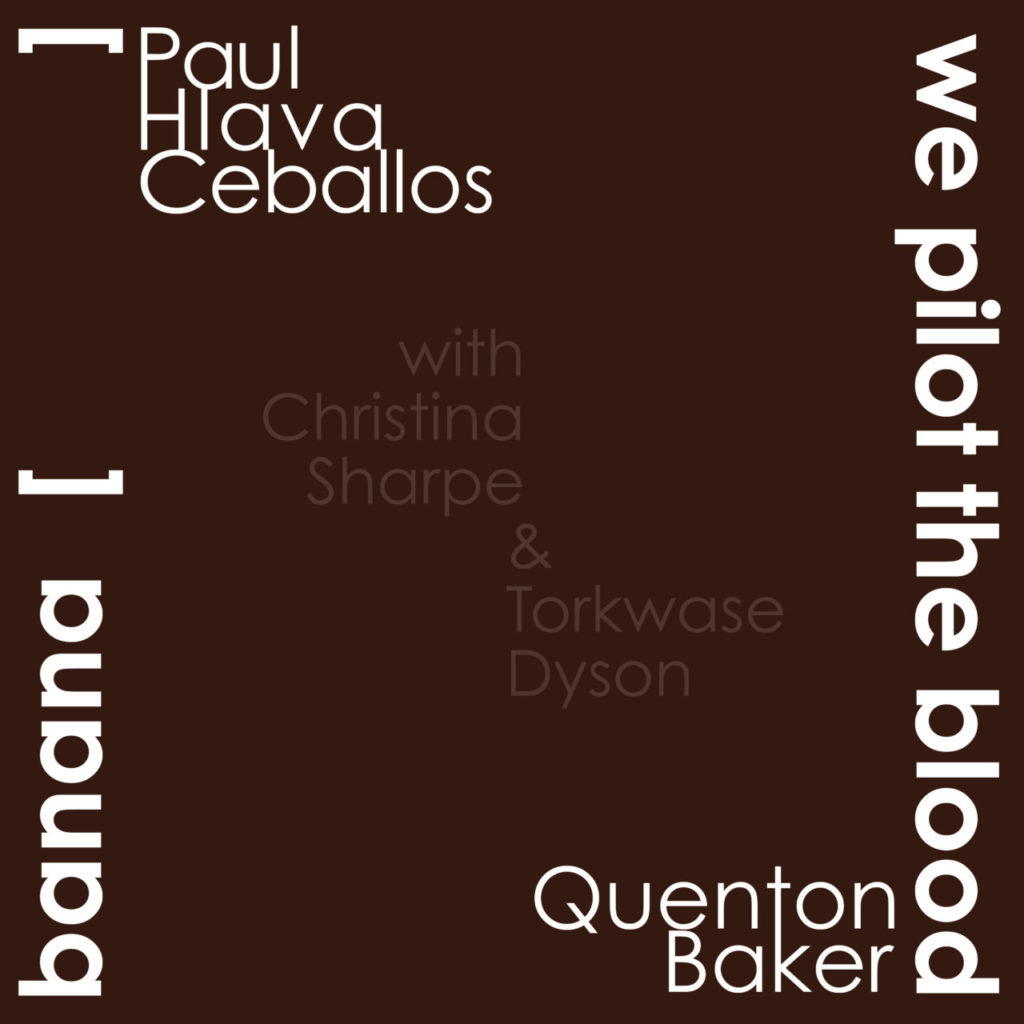

One day, I asked if he would be interested in pairing our writing together. Soon, with essays by Christina Sharpe, images by Torkwase Dyson, poems by Summer Hart, and the work of our editor Anne de Marcken, the project took on a life of its own.

On the release of our collaborative book project, Banana [ ] / we pilot the blood (The 3rd Thing Press, November 2021), I chat with Quenton Baker about emotion in research, blackness, language, and our work.

Paul Hlava Ceballos: I love “we pilot the blood,” and after seeing Ballast painted on the walls of the Frye Art Museum, I had the urge to hold that document; there was something tactile about the history as you’d given it to us. So now I have the chance! Obviously, we are both working with historical texts, and as someone who hasn’t had to choose between source texts, I am wondering how the Senate document for the revolt aboard the Creole came to you?

Quenton Baker: i honestly didn’t think it would take this long for me to arrive at an answer. i had to sit for a while with the concept of choice in regards to this project. i don’t think i got anywhere helpful, but i feel bad about leaving you hanging for so long. this is a difficult question for me, i believe, because the relationship between choice and the document i used for this project is so fraught. when i set out to work on this book, in the initial research phases, i had a completely different idea of where i was headed. i thought that i would uncover something, anything, about the people on the ship and build a work around their lives. but the more i looked, all i found was erasure. a total disappearance at best, and a re-writing or a dramatizing at worst.

so i had to switch to a kind of excavation. or, perhaps, retribution. the senate document then felt like the logical choice, to return a facsimile of the rupture; something to drill down into and break apart into a different logic. i think i would say similarly though that i had no choice. beyond the very limited material on this revolt to begin with, once i encountered the senate document and read the kind of erasure and obliteration replicated in it (a kind that i am all too familiar with), i don’t think i had any other option except to use it as the text for this project.

rage and anger and violence are byproducts of living in an anti-black world. there are only so many places that i can put it that won’t get me killed or harm someone that i don’t want to harm. but when i read this senate document, i wanted to harm it. i wanted to visit a certain kind of violence upon it. and so i did.

i’m not sure if you felt a similar kind of rage in sifting through the massive amount of texts you went through, but i’m curious about your emotional state, or perhaps release, in writing your project. i know lots of people have lots of thoughts on poetry as catharsis, but i’m thinking about the ways our personal and/or poetic emotional selves are present when doing this kind of work—work within someone else’s field of language—how, if at all, does that play out for you?

Paul: I felt a lot of rage working through the banana poem. It’s interesting you asked me that because nobody else has, though it’s such an integral part of the project. These documents are more than artifact; they’re personal. When you looked for people in your text, what you found was erasure as a form of state violence against them. I ran into a similar problem in that the lives and deaths of Latin American farmers aren’t recorded. The assassinations of poor laborers don’t make American newspapers. These are black, indigenous and mostly non-white people who bear the sometimes fatal consequences of international politics and corporate trends. But here in the United States, people I met seemed to have no idea that a banana held any meaning. Well, it was never about the banana. It is about resource extraction that we take for granted here and our relationship to the erased people who bring those resources to us.

I felt a lot of rage. I looked up the word “redact” recently in an etymological dictionary, and learned it came from the Latin for “drive back” but also “to bring forth what wasn’t visible before.” I love your word, “retribution.” The first line in my poem is a partly redacted sentence from a CIA document titled “Labor Situation in the Banana Zone,” and I like to think that my poem subsequently works to fill in that space. The sequence of names of banana workers assassinated in the past decade took me five years to compile and is the only catalogue I know about of its kind. The shorter, three page version is in our project and even that is admittedly hard to read. Would you understand if I told you that I wrote it driven by anger? That I wanted to hurt the reader? I wanted to hurt the reader the way the workers were hurt, the way that we who grew up knowing this history are hurt every time it’s clear another person could spend their whole life not knowing this history. I am thinking that mere witness is insufficient. There is no room for emotion in note-taking.

By researching the assassinations I found, through labor and human rights websites, some interviews with the banana workers themselves. The people I learned about from the poem—I got to read their own words, to see them on the page! If you’re asking about my emotional state, I cried openly in a coffee shop. Not catharsis, but I stumbled on an act of emotionality that allowed me a much fuller relationship to the world I was writing about.

You said there were no people in your document, but in your poem there is a speaker, an I. How did you uncover this I, or become inhabited by it, and where did it take you?

Quenton: i really appreciate that we are joined by our rage. i feel similarly that i wanted to cause hurt. not toward the reader but toward the text. a kind of habitable hurt, a violence you could live in. i think the i is linked to that violence. there are people in the document, but they exist as object. they’re referred to by the white slavers or by the white diplomats, and the leaders of the rebellion are sometimes mentioned by name, but you’re right in that there is nothing approaching an i, nothing internal, nothing in anyone’s own tongue (of course, even if it were it would be under duress).

i think inhabited is definitely closer to what happened for me during the writing process than uncovering. i see the senate document both as a text and urtext, in a sense. it is an original (and, of course, profoundly unoriginal) blueprint of the kind of obliteration that happened/happens to the slave. the slave does not exist, the slave is non-being, the slave occupies the object position of the socially dead. so a document like this senate record, even if it did have the voice of the rebels, couldn’t actually contain them; they would always be buried beneath it, or rather they’d always be the negative space that made the text legible and coherent. so it was less about uncovering or excavating or speaking for or finding, because that would be impossible, given the condition of the slave. it’s unknowable. but i could listen for echoes, and that’s how i think of these poems. as echoes, as ghosts. the i’s that appear are a kind of resonance or reverberation that sounds when you strike a blow, when you tear apart a text like this.

i’m really curious about your research experience. i’d like to hear about your process but what i’m most interested in is how you felt during it. you mentioned that at least once instance of your research led you to cry openly in a coffee shop and you said it wasn’t catharsis. i’d really like to hear more about that, about the bond or connection that formed for you during the research process (if one did). i think of research as a strangely intimate practice, and i’m curious about your thoughts on what it was like for you.

Paul: Agreed, research is an intimate practice! By acknowledging those who came before us we are communing with the dead. This makes me think how differently the past and passed on are perceived in US American culture versus many Latin American ones. Whereas in the US, ghosts are the stuff of horror movies, in my home, I lay flowers on an altar to keep my dead alive.

For me, researching was connected to the poem’s imagined audience. As I mentioned, my first imagined audience didn’t know about bananas sociopolitically. I wanted to disrupt that oppressive amnesia while simultaneously disrupting the system of grammar that upheld such oppression. The research was easy—propaganda from the United Fruit Company, CIA documents, and other corporate press releases are easy to find. And it was fun! One self-proclaimed history book for example, Conquest of the Tropics, funded by United Fruit and about United Fruit is so over-the-top racist—I mean, it’s a joke. And I chopped that book up. And chopped up CIA docs that tracked workers. And mixed them with agricultural words such as cut, de-hand, burn, and bury. The work felt good.

But I was disquieted by the fact the poem still relied on the words of the state. That’s when I began researching banana worker assassinations, what I think of as a kind of “say her name” section. The work was harder. I would spend hours after work and eight hours on Saturday and Sunday reading of under-reported massacres on non-profit and union databases. Years with multiple books on my lap, reading of paramilitaries, bullet wounds, the murders of people who could have been my tíos or distant cousins. The fact of it was too heavy. It felt like a wedge splitting a log. I remember a beautiful day in Capitol Hill when I saw people brunching and laughing and someone chatting with a police officer and I couldn’t breathe right, I was trembling—what is the word, simulacrum?—is this also part of what I was researching, a neighborhood like this? And who was safe here, was I safe here, and where were the banana workers in relation? Around the point I couldn’t bear to continue the research, I ran out of names. This is not to say the list of names is complete, but I couldn’t find any more names in the databases I had access to.

Actually, here I was bothered by the fact it was only the banana workers’ deaths that represented them. Nobody deserves to be so immersed in suffering and I didn’t want to replicate that for them in the poem, or for an audience who might have similar traumas. This is where those connections formed. For example, there was a banana worker I had been reading about for years, and the only information I had was details of his assassination, articles about that shooting, and then one day I clicked a link and there he was, speaking. Hernán Bedoya. His voice, mannerisms, the sweat beaded on his lip from the tropical heat. This was the emotional moment in the coffee shop I mentioned. I broke open. He was alive. In this way, the poem altered me, not in the writing but how the writing allowed me to relate. Bedoya and a few others I quote in the poem—they are my community now. I take them with me.

I am realizing how much audience shaped this poem and am interested in audience in your work. Maybe the banana poem’s imagined audience was a kind of return to my upbringing in a majority-minority neighborhood. Do you think your upbringing and subsequent leaving your hometown affected what you write and who you write for?

Quenton: i think (and thought) about audience obsessively. and it relates to what you said about the only record being trauma or loss. what does it mean when your only visibility to the archive (or to the world at large) is through your pained body, your death, your unjust and early end? what does it mean to live in-between all that? the monstrous reality of a perilous life, balanced against the normal/mundane/wonderful things that can happen in a human’s day-to-day existence. caught between social death, or non-being, but of course you’re fully alive to your loved ones, to your community. and it all matters. you can elide or omit any of it, but neither can you pretend that some of it is the whole story either.

so my considerations of audience are tied to that double life. i want black folks to feel seen, understood, in all of that complexity that comes from life on the knife’s edge. but it still is life. we’ve built it, we survive in it; we make the uninhabitable habitable. and i think that’s the project that i try to attend to in my work. how to make this alien and terrible world that requires our death habitable. how to celebrate our survival in it without limiting us to only our survival. how to address trauma without reenacting it, or thinking that makes up the totality of who we are.

of course, i don’t decide who interacts with my work, but i think my consideration of audience begins and ends with black folks. because of the nature of the work, i don’t think i can really imagine audience beyond that. because my main considerations are harm (as in not doing it) and redress (offering it, however flawed it must be). and it’s expansive. if my goal, and it is, is to avoid the fraught, dangerous semiotics of english in regards to blackness, then that takes all of my attention and whatever linguistic skill i might have. working in this language, one that is so heavy with terrible hooks into and from the white imagination, which is thick with so much horrible history and harm, so much layered danger in terms of associations. i feel like i have to clean my words, wash my bones, before i can present them properly.

and that leads me to my question for you. what do you think about working in (against/across) english? i know you don’t solely work in english, but for me it’s a really difficult relationship. there are so many pitfalls because this language has been (and is) used for so many terrible projects and goals. how does that affect your approach?

Paul: As I think of harm and redress, I realize so much of what you are doing is the “wake work” Christina Sharpe talks about. And I am realizing that English was also brought aboard slave ships—how painfully finite it is to think inside of! But the way you bring forth language atemporally (to echo Sharpe again) so that I hear voices of the people aboard that ship and also present day black people is deeply moving.

My relationship to English is fraught, and it’s the only language I am fluent in. I grew up not understanding my family’s most intimate conversations, nor my tíos and primos; I was on the outside of the very linguistic lineage that connects me to what I love most. So within my primary language, the English I devote my life to as an art form, there is always the quiet thing, the thing that isn’t spoken. And I want to recognize here that Spanish is also a colonial language. Some of my ancestors spoke it and some ancestors spoke a language that those people eradicated. So that’s another layer of removal—family stories in languages that have been buried. Maybe cutting away history books and CIA documents is an excavation, or retribution, for those family members. I am trying to put them back together, or remember them.

To be direct, I speak Spanish poorly because of assimilation. My parents thought erasing it would lead to more opportunities, which I experienced as loneliness and dislocation. It was confusing to research in Spanish, and demoralizing. I couldn’t skim a history book. I spent a day on a single newspaper article about an assassinated banana worker. But to be complete, my text needed that person and that language. And I learned that I needed them too. So I started incorporating Spanish from my childhood into other poems too, even just single words or idioms, and I think my writing has really grown because of this. I am learning and re-learning the only language my abuelos spoke by researching and writing about banana workers.

So I’m really excited about the possibilities for connection that Spanish is opening up for me. One of those is this work in collaboration with you and Christina Sharpe! I always thought of the banana poem as a collaboration with documents and workers. Is your piece collaboration? I am also thinking about the solidarity between black people on that ship, many of whom I assume didn’t know each other as they rose up against their captors. And maybe as a final word, you can say what you were/are working on around this poem and mental space?

Quenton: i definitely see your banana poem as a collaboration, and i really appreciate and respect the work that goes into something like that; to do it properly, to honor those involved. i do think of my piece as collaborative, and i’m honored that our work can exist together in this way (along with christina sharpe’s work) because it opens up new/different collaborations that i couldn’t have been thinking about previously.

and i suppose, beyond just this project, i think of all my work as collaboration. the idea of history and poetic lineage factor heavily into my process. i’m acutely aware of all the ways that my work is made possible by the artists and writers and thinkers that shaped my ethos and i think of my work as being in constant conversation with theirs. poetry, to me, is the expansion of possibility and i don’t think anyone does that alone. nor should they. what a monumental task.

you mentioned solidarity, which is an interesting thing to think about in the context of the revolt. there were 135 (roughly, accounts vary) enslaved people aboard that ship, and only eighteen were involved in the revolt. we don’t/can’t know how many of the 135 knew and declined to participate or just weren’t made aware. we have no way to make an inventory of their decisions. we do know that five people elected to stay on the ship and return to new orleans. and perhaps more than the eighteen that took control of the ship, when i was working on this project, those five stuck in my brain. it’s impossible to understand decision making in the face of an obliterating horror as complete as chattel slavery. i’ll never know why those five people chose to return to the united states, but it illuminated a larger point that i thought was really important to the project. it’s easy for people to look at something like a slave revolt and think of it as a positive story, an end to captivity. an escape. but it’s an escape within an anti-black world, enabled by a different colonial power, with passage into a different colony. and there is positivity there, of course, but it’s flawed redress.

and that was the animating force for me. how to live in the midst of these colossal, terrifying, and yet ultimately insufficient acts of liberation and meaning-making. the atemporality, as you mentioned, comes from the reality that, of course, we still live in these survival choices. we can’t escape a world that has codified black non-being, but also we can’t fully live in it, because our humanity is conditional and obliteration looms. so i wanted to occupy that interiority. not to report on it, to make it plain to a world that doesn’t deserve to see it, but to simply acknowledge its existence. as a testament to black survival, black meaning-making as we live life under constraint, as fred moten would say.

Paul: Thank you, Quenton.

—

Quenton Baker is a poet, educator, and Cave Canem fellow. His work has appeared in The Offing, Jubilat, Vinyl, The Rumpus and elsewhere. He is a 2021 NEA Fellow and the author of This Glittering Republic (Willow Books, 2016).

Paul Hlava Ceballos is the recipient of the 2021 AWP Donald Hall Prize for Poetry, as well as fellowships from CantoMundo, Artist Trust, and the Poets House. His full-length book, banana [_], is forthcoming from University of Pittsburgh Press in 2022. He lives in Seattle, where he practices echocardiography.