Appreciation // Safia Elhillo’s The January Children

by Lena Khalaf Tuffaha | author of Water & Salt

Appreciations, a new series at Poetry Northwest, aims to introduce you to new, or new-to-you, collections. It’s our digital version of handing a book to a friend: Read this. We think you’ll like it. The first entry in this series was Erin Malone’s appreciation of Lena Khalaf Tuffaha.

The first time I heard Safia Elhillo read was at an AWP 2016 offsite event in a noisy room pulsing with poets and writers. These were her friends, and they hurled cheers and encouragements up at the stage—”fuck it up Saf!”—the love palpable and electric. Then she began to read and all I could hear were her searing, seamless lines:

The first time I heard Safia Elhillo read was at an AWP 2016 offsite event in a noisy room pulsing with poets and writers. These were her friends, and they hurled cheers and encouragements up at the stage—”fuck it up Saf!”—the love palpable and electric. Then she began to read and all I could hear were her searing, seamless lines:

& what is a country but the drawing of a line i draw thick black lines around my eyes and they are a country and thick red lines around my lips and they are a country.

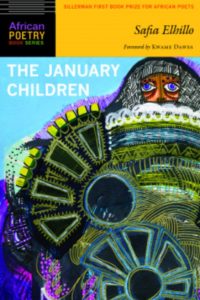

Safia Elhillo is a highly-accomplished poet. Her accolades include fellowships with Cave Canem and the Poetry Foundation’s Poetry Incubator. She is the author of two chapbooks, The Life and Times of Susie Knuckles and Asmarani, and the co-editor with poet Fatimah Ashgar of the forthcoming anthology Halal If You Hear Me. She is also a teaching artist with Split this Rock. The January Children, published by University of Nebraska Press (March 2017), is her first full-length collection, and is the winner of the Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets.

The poems of The January Children are laced with smoke, the perfumed smoke of incense entangling itself in a woman’s curls, the tender smoke of cigarettes at a concert hall in Cairo, the sulfur smoke of a country burning. I take long drags of these poems, filling my lungs with them. They rhyme with my own ache of dislocated homelands and the vagaries of language, but they are distinctly Elhillo’s.

In many of the poems, she is applying for the imaginary position of girlfriend of a 1960s Arab heartthrob, Abdelhalim Hafez, who sang to “el asmarani”—the Arabic term for dark-skinned beloved. The Hafiz poems are the best kind of poetic obsession, and in Elhillo’s capable hands they transform from personal meditations on love, loss, memory, and mortality, to politically astute explorations. Elhillo’s poems engage themes of Arab and African identity, migration, race relations, and the history of her native Sudan. In the poem “why abdelhalim hafez’s girl” she writes:

he sings an endless echoing note / & anyone can be the girl he says browngirl & never says / how brown he’s been dead my whole life / he’s used up he’s eulogizing home.

Hafez died relatively young and suffered a painful waterborne illness from childhood which added to his lore among fans. Against the backdrop of his fleeting and tragic life, Elhillo crafts counterpoints to questions of geography, origin, and mother tongue so deftly woven throughout the book.

The January Children opens with a prayer in the cadence of a translated Quranic passage: “verily everything that is lost will be / given a name & will not come back / but will live forever.” Safia Elhillo’s poems name loves and worlds even as they slip through our memories and our languages. And for that and the treasure of these poem, I send up a heartfelt Ameen.

—

Lena Khalaf Tuffaha is an American poet of Palestinian, Syrian, and Jordanian heritage. Her first book of poems, Water & Salt, is published by Red Hen Press. She is the winner of the 2016 Two Sylvias Prize for her chapbook Arab in Newsland. Her poems have been nominated for the Pushcart and Best of the Net, and have her newest poems are forthcoming in Alaska Quarterly Review, Black Warrior Review, and Winter Tangerine. You can learn more about her work at www.lenakhalaftuffaha.com.

—

photo credit: Seabird NZ Screaming ghost (license)