A Myth Against Empire

by Dujie Tahat | Critic at Large

H of H Playbook

Anne Carson

New Directions Publishing, 2021

“We were, most of us, fleeing the reality that man is alone upon this earth. We ran from a fact of solitude to a myth of community. That myth failed us because the moments of test come most often when we are alone and far from home and even the illusion of community is not there to sustain us.”

– Murray Kempton, Part of Our Time: Some Ruins and Monuments of the Thirties

Anne Carson’s H of H Playbook is not a play, but a playbook. As in its bookness—or the materiality of the book itself—is the first, most important thing a reader experiences. While it is not a play, it is a book that includes the trappings of a play, that makes a play, that plays. The book, then, becomes the site of drama. Like much of Carson’s previous work, genre is not quite a secondary consideration as one nearly obliterated in the immaculate obsession of what a book is, does, and means.

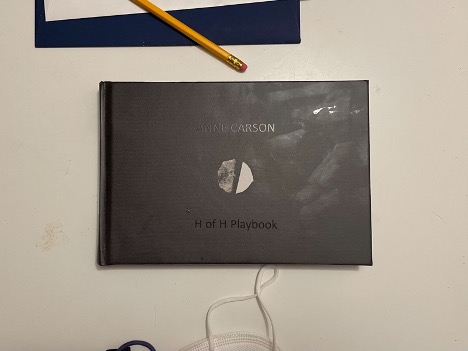

H of H Playbook is a thick hardback (so it’s costly as books go). It’s a bit awkward to handle at 6” x 8” landscape orientation. It requires both hands, demanding a total physical attention and investment to engage with at all. No coverslip, the front is all matte black, the author’s name and the book title, also in black, offset only by glossy ink. In the middle is a white, abstract image, one-inch in diameter. When I first held the book, I thumbed the spot, thinking someone had inexpertly peeled off a sticker, only to find it as smooth as the rest of the cover. Was it meant as a token? A hoof mark? Something I couldn’t imagine?

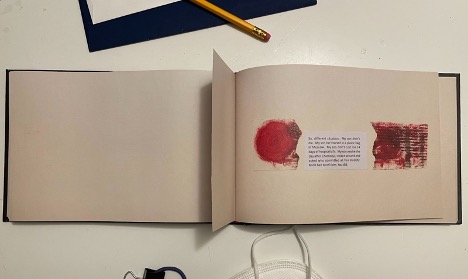

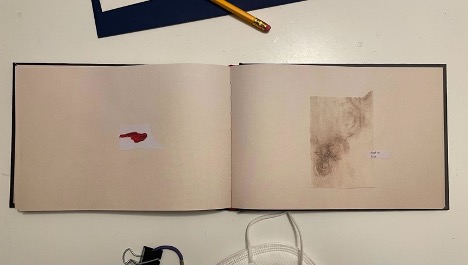

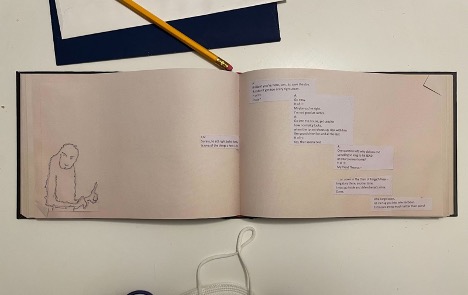

The text itself, if flipped through, might be best described as collage: drawings and paintings, mostly abstract and some figurative, break up the text, which, page to page, ranges in size and length from a single word to multiple fully-justified 2” x 5” copy blocks. All of it was produced not in this book. Which is, I suppose, true of all books. But in this instance, all its attendant elements were printed, painted, and sketched on pages that were cut, positioned, and scanned into the thing that was reprinted for us to hold and read. Before we get to the text proper, there is a blank three-page sequence in which the first page is ripped in half, the second three quarters of the way across, leaving room to see the third in its full length: creating a kind of stair-step effect, a short descent into the work. Though one gets the sense these are deliberate choices, there seems no obvious logic to the way these elements are arranged. To read it, we have to suspend a desire for clarity. The book is meant to be experienced, and experience—if we are in it and not steered by the past nor future or the fixed nature of story as H of H Playbook asks of us near its end—is infinitely mysterious.

If much of the book’s mystery rests in its materiality, the clues to what it reaches for lie in its seeming imperfections and deteriorations. Streaks, stains, smears, and smudges all characterize the artwork. Even the figurations seem serendipitous, shaped by the coincidence of happenstance. Interestingly, the only colors are primary: red, yellow, blue. When you open the book, the first thing you see is a red circle on the inner cover, a bleed from the red permanent marker circling Thebes on a map of ancient Greece, opposite. Though we don’t know it yet, functionally, the book is locating us. Have I mentioned yet that H of H Playbook is a rendering of Euripides’ The Madness of Herakles billed as a translation of the tragedy originally performed in 416 BC?

That is the way the book works. Information is not nearly as important as the modes of and structures within which it dispenses information: the latter—once a recipient like you or I is placed in it—being a process we might call knowledge. H of H Playbook is about a myth but the myth takes a back seat to the mythmaking. It’s not enough to say it is a contemporary reimagining of Herakles as a poor, white combat veteran who returns home to his wife and kids, who live in an Airstream trailer outside of their old home now owned by Lykos, only to murder his family in a brutal episode of post-traumatic stress disorder. Although it is that. It draws on the structures of contemporary life—masculinity, nationalism, war, capitalism, and whiteness—to expose the structure of the hero myth. It’s distinctly Western at the turn of the 21st century in its making, positioning the protagonist—referred to as H of H (Herakles of what? Hero? Hera? Here?)—against the Russian revolutionary marxist Victor Serge. The scope of the book’s tone ranges from sarcastic to earnest, utilizing the most obvious rhymes, shifts, and breaks to remind us of how the structural choices being made shape all our experiences: the characters’ as well as the reader’s. It is more than translation of just language (which is never just language) but translation across and through cultural contexts. It is writing against the propagandizing of glory, war, and veterans as heroes. It is carrying across our humanity.

* * *

In contemporary American culture, war veterans were made heroes when the government stopped financially supporting them. In 1932, 43,000 demonstrators, wives, children, and allies of 17,000 World War I veterans, gathered at the Washington Mall in the capitol to demand the bonuses they were promised for their combat service. It was the height of the Great Depression, they were without work and many without homes, we might today refer to this as an encampment. On the order of Herbert Hoover, the encampment was swept by DC police, who in the process, killed two veterans. The Army was called in and men who’d later become heroes in the American mythos—Douglas MacArthur, George Patton, Dwight D. Eisenhower and J. Edgar Hoover—brought in the infantry, cavalry, and six tanks. The remaining campsites and belongings were burned. Today, veterans are overrepresented in the national population of people experiencing homelessness; which is to say, they continue to disproportionately feel the effects of the face-saving, short-sighted homeless encampment sweeps. As Carson reminds us, all histories and the myths that drive them are happening at all times; the risk always residing in how power uses them to reify its own structures. Deservingness has always been the rub because it creates, through implication, a category of people who do not deserve the most basic necessities.

The Bonus Army, as it was colloquially referred to, has, by now, been largely snuffed out from collective national memory. World War II gave us a greater moral enemy to rally around. However, empire’s impact on its foot soldiers only grew. The unpopularity of the Vietnam War gave context for the first ever PTSD diagnosis—with almost a third of all infantrymen returning from combat being identified as having symptoms. Correspondingly, Hollywood went to work, expanding its depictions of broken, blue-collar white men cum heroes to include the murder of a foreign people in their hinterland. The myth prevails and reiterates with every Blue Angels show at Seafair or saccharine, gaudy presentations of the American flag by the armed services before all NFL games. These gauche displays want us to forget that the men sent to war, whom we valorize as heroes, return not with glory but violence. They want us to forget that while the incarceration rate for veterans is nearly 10 percent lower than for civilians, a far greater share of incarcerated veterans have been sentenced for violent offenses (64 percent versus 48 percent). They want us to forget that nearly one-third of post-9/11 veterans have exhibited non-job-related physical aggression and a further 11 percent engaged in “severe or lethal violence.”

The American project must frame war as a moral enterprise in order for the public to accept it. This structure and context reifies both mythologies – that of the hero and of the nation – to place our collective identity on the side of moral good. However, these same myths erase and obliterate the individuals at, in, subject to, and enacting war. In response, Carson creates an interiority for H of H, the character, that is all context. The middle section of the book is his inner monologue summarizing his infamous 12 labors, giving him agency, self-awareness, and a sense of humor when he skips 3-8,10 and 11 because he’s bored. The ancient Greek context gives the modern-day protagonist substance—such that when the tragedy happens, when the point is being made about the violence that war veterans bring home, the PTSD and paralyzing social structures they’re trapped in, we then have to reckon with dead families in both the historical and contemporary contexts. It exposes the flattening effect of all myths.

While H of H is coming to terms with his killing Megara and their kids, his friend Theseus arrives. Theseus sees H of H as a person and not a character in a play or hero in a myth. He is the only character who seems to be aware of the structures of the book and those who benefit from them remaining static. Theseus represents—and offers to his friend—a way out. H wants suicide, but Theseus knows death affixes the myth and denies him a death in order to preserve the fullness of his humanity. Empire makes martyrs out of soldiers, so it stands to reason that H’s response to facing his own monstrosity is to martyr himself. That’s his training. That’s the playbook. H justifies himself, thinking he’s earned it through his labors, and again, Theseus denies him: “I’m not saying move back towards life, I’m saying the future isn’t elsewhere. We’re locked in a spaceship, H of H, we have nothing but continuing. What could be more useless than you limping offstage to die in a dead language? Of course the guys upstairs would love that.”

We’ve distilled the entire experience of war for individual men to a single data point: hero. Today, we’ve forgotten that the hero myth—as Euripides envisioned it—is meant to be a warning. The guys upstairs, atop the structural forces that seek to stamp out difference and dissent, pay good money to keep it that way. Carson, however, refuses. H of H Playbook is a submission to our collective conscience, a treatise against empire, and a reminder that there is no myth nor story that can replace actual, material human experience. If we can contend with those facts—and only then!—we may begin to see each other more fully and make choices that attend to and care for each other’s humanity.

—

Dujie Tahat is the author of three chapbooks: Here I Am O My God, Salat, and Balikbayan. Along with Luther Hughes and Gabrielle Bates, they cohost The Poet Salon podcast.

Anne Carson was born in Canada and teaches ancient Greek for a living.