Interview // Amanda Knowles on Rothko, Frost, and Growing Up the Daughter of a Scientist

“Sustained by the Process”: An Interview with Visual Artist Amanda Knowles

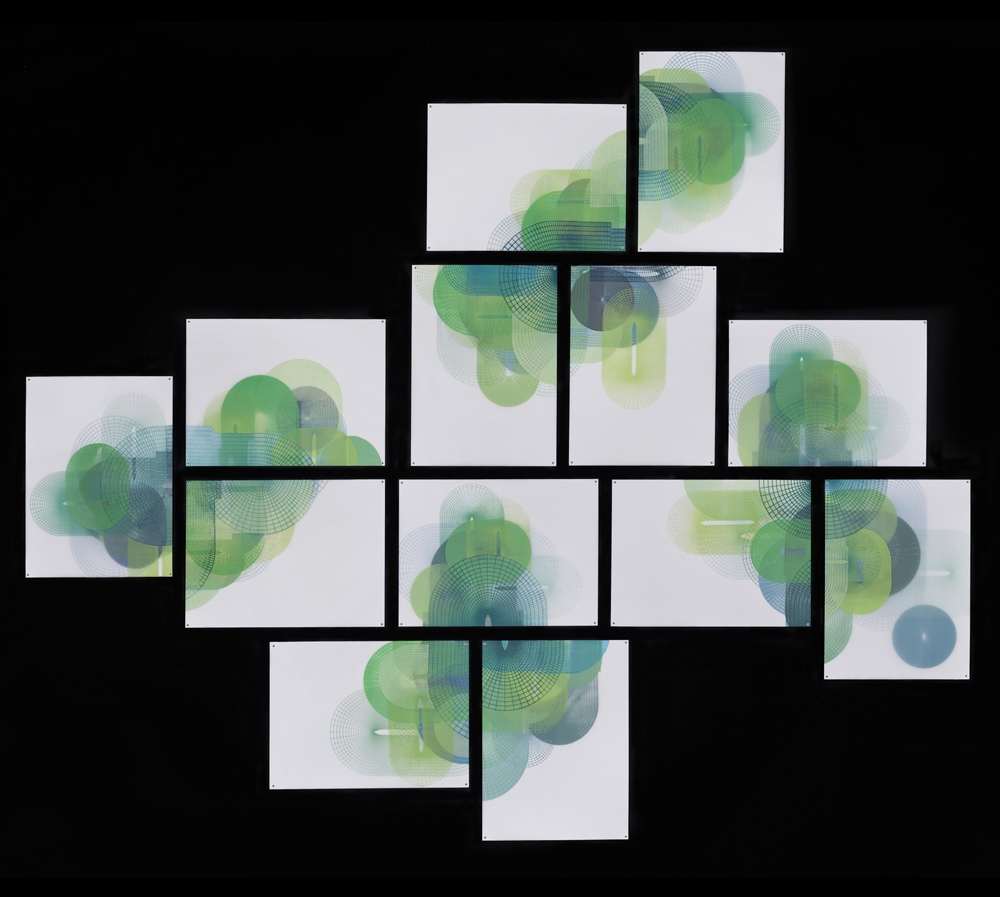

This conversation between artist Amanda Knowles, who created the cover art for PoNW’s science issue, and Community Page co-editor Nari Kirk took place via email during May and June, 2012.

NK: In your Artist Statement, you write eloquently about your interest in rendering scientific concepts in a new way for contemporary culture. You write that you “hope to draw an emotive or intuitive response instead of leading the viewer to think about the world in terms of reason and logic.” This reminds me of Robert Frost’s famous essay “The Figure a Poem Makes,” in which he asserts that a dynamic poem “begins in delight and ends in wisdom.” In light of your art’s aesthetic, what do you make of this notion? What associations exist between emotion and wisdom, especially given the commonly held view that science is about knowledge and, as you say, reason?

AK: The whole of the Frost essay is perfect, yes: “Scholars get [their knowledge] with conscientious thoroughness along projected lines of logic; poets theirs cavalierly and as it happens in and out of books. They stick to nothing deliberately, but let what will stick to them like burrs where they walk in the fields.” I was raised by my mother, a scientist, and from what she does for a living have gained an understanding of the importance of facts and knowledge. Still, I sneak through the physics library as one about to be caught for not belonging. While I can understand scientific inquiry, my strong suit is a more emotional, perhaps intuitive, experience. So it is no shock that I use the language of science to create a thematically undefined picture of the world. Each of my creations, indeed, begins in play (or “delight”) and changes through my working. After each move the piece becomes new again and I have to recalibrate to consider the next move until I near the end, where I’ll kill and resuscitate the piece multiple times, figuring out the proper recipe. The process could have hundreds of different outcomes, but only the one fought for and hard won remains.

In the end I am no wiser from the work. Wisdom only comes as I sense the edges of each piece’s possibility. For me the search is the important part, not the knowledge, and I am sustained by the process. I, surely, continue to make the same mistakes in each piece, unaware as I search for each artwork’s finish. My hope is that, at the end of their revisions, the images provide a more lyrical response to the hard facts of the scientific method.

NK: The creation, obliteration, and regeneration procedure you describe sounds very much akin to a writer wrestling with her text. What synchronicity have you observed between a work of visual art—like one of your prints—and a work of textual art?

AK: I find similarity in the way that a visual work and poetic work are made: storyline in some, image in others, emotion in still others. There have been projects where visual artists make work based on a poem. In the last couple of years, Seattle’s Lawrimore Project presented a series of interesting shows that matched artists up with poets/writers. And there are poets that use visual art as their jumping-off point. Hugo House and Henry Art Gallery offer a “Hugo to the Henry” class about using art as a springboard for writing.

I’d love to see artists and poets grow their work collaboratively, not building their art or poetry from a piece already made, but forming it together. Yes, there is synchronicity: We are working off the same sort of ordering of the world, but using different tools, different strengths.

NK: Your responses make me think of epistemology. For instance, your mentioning of the scientific method brought to my mind our culture’s dependence on proof, the constant need to know for certain. But what people often use as a synonym for knowledge is data, which really means numbers. Your work—without pretense or agenda—counters such simplified interpretations of knowledge. Even though you go so far as to say that you are “no wiser from the work,” I can’t help but think that artistic creation still fosters some kind of knowing, if nothing more than what can’t be known. How far off base am I here? Help me out.

AK: Art doesn’t provide the same acquisition of knowledge as does our schooling or Google or what growing up in a scientific family did for me—although as I am thinking about it, even as my family engaged in experimental science, they trusted the process, allowed experiments to play out through time and trial. This sort of experimentation is really important to my work, trial and error, and the research that I undertake is primarily just the work itself.

NK: What about the relationship between art and the outside world? Recently I’ve been reading about what smart individuals like Pamela Haag and Jonathan Franzen consider to be a crisis of our time: the constant noise of the private becoming public through mediums such as television and social networking, an overload of personal information that numbs us to true intimacy. Your work seems to desire intimacy—between art and science, yes, but to a greater extent, between languages, experience. In what ways does your work seek to pause, even transcend, the noise?

AK: I think that this question is not easily answered by me, the artist. I can say that “transcending the noise” is what I hope to happen for the viewer. My time in the studio, my process of working, is just this, a slowing down of time. Its abstract nature is important to me, as it gets us away from the abundance of storyline or content available in the outside world.

A lot of my art is about the negative spaces, pointing out the spaces in between where “nothing” is happening. In places, sections are whitened back to allow the chaos to subside. The work is evident in the piece, the history of my actions, but in it I attempt to get a simple image.

NK: Some people see art as escape, while others see it as immersion in reality. What do you make of these views? How can they be mediated?

AK: I am pleased if people think about art at all. I keep trying to think about art as a whole in this question, but find myself gravitating to the breakdown of kinds of art. There are, indeed, some who respond to art with an agenda and that can reiterate the world that they have set up, while others find work that takes them outside of their reality more interesting, and luckily there exist both kinds of art. I am not sure that we have to find a middle ground where all can coexist—I love the fact that everyone can find something that speaks to them specifically. This makes for stronger allegiances, stronger opinions, and stronger feelings for certain art and artists. We do not all have to agree about what art is or should do. I relish how it can do both or neither even as it attempts to be one or another type of art. I think that art can do it all.

That being said I have never thought of the work that I do or that I like as either “an escape from or an immersion in reality.” But it is something that I base every travel experience on—when I look at ikat in markets and museums in Indonesia or visit the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston or the Crown Point Press in San Francisco, even the MoMA or high-end clothing stores in NYC. In this way I can see it as both an escape, but also an immersion in the local culture.

NK: Speaking of local culture, how—in your estimation—does thePacific Northwest contribute a particular element or spirit to the national art scene?

AK: It depends on what direction you are looking in, and you can look in many different ones. Perhaps the artwork from the Pacific Northwest incorporates the outside world—our mountains and trees—into the lexicon of contemporary art through image (such as Mary Iverson’s and Gala Bent’s work) or material (I think of Leo Berk). Printmaking in Seattle is bolstered by the strong presence of Seattle Print Arts. And, of course, in the world of glass art we are at the top of the list because of Chihuly, the Pilchuck Glass School, and the recent addition of Tacoma’s Museum of Glass. This influence of glass can even be seen in diverse ways (look to Etsuko Ichikawa). But more so the Pacific Northwest has deepened the pool of art throughout the country, both curatorially and artistically. Seattle has an enormous number of artists making all sorts of good art as well as people doing interesting curatorial work. The Pacific Northwest is a strong region for the visual arts, perhaps not like New York or Los Angeles, but with a large group of active artists experimenting and creating innovative things.

NK: It seems to me that many people don’t know what to make of such artistic evolution, especially if it strikes them as inaccessible—poetry, for example, has long faced obstacles in finding broad readership outside the Academy. People often turn to verbal and visual texts for either information or entertainment, neither of which requires much engagement, and this passivity prompts resistance to art. What should viewers bring to your art? How much does their participation mean to a piece of art’s completeness?

AK: Several weekends ago I went to see the Rothko show at the Portland Art Museum. The room was crowded (this is a good sign). When I entered the section of his later work I walked right into a conversation about the work—how he used paint, etc. What bothered me most was that they missed the entire point. They were supposed to be sucked into the effect of the painting, taken over by how the piece made them feel. I mean, this was Rothko; the feeling was supposed to be like religion, and still they stepped back to comment on the surface of the piece.

I don’t really think about the viewer in my work because I know that I cannot urge someone to act or think in a certain way. I hope that there is a viewer, but the pieces are usually about my time in the studio, my distillation of the motion of making the work. Perhaps this is why people find abstract art enigmatic.

As a teacher of art I try to show students the nuances and the work that go into even the simplest piece of art, so that the idea of “my kid could do that” around a Mondrian, or some other such piece, is dispelled. Perhaps the viewer’s unwillingness to delve into work they see as hard is laziness, but I tend to think it derives from not knowing where to begin or from a lack of connection. I am not certain that this idea of inaccessibility of the abstract (thought or art) has ever changed. The initiated, indeed, find it easier to engage, so my role as teacher makes me want to initiate as many as come to me to learn. It seems that if someone gets a little bit they’ll more easily understand more, a slippery slope, a gateway drug. (I am happy to see that I still am an optimist on the subject.)

NK: I love the anecdote about your visit to the Rothko show. Art with a capital A seems to attract an elite crowd that revels in its lofty lexicon of technique and metacommentary—perhaps a little like what you and I are doing right now, I suppose. So if we halt our pontificating and bid this interview’s readers to go experience art, where, in the Pacific Northwest, should we send them?

AK: Yes, I’d love for them to go see some Art. The more often it’s viewed, the less obscure it becomes. Seeing, like anything else, comes with practice. There are so many places to visit. My favorite local art walk is the Seattle (Pioneer Square) Art Walk, on the first Thursday of every month. Pioneer Square is where many of the commercial galleries in town are situated.

Some of my favorite Seattle galleries are the Francine Seders Gallery (in Greenwood), Greg Kucera Gallery, Davidson Galleries, and G. Gibson Gallery. InPortland, Elizabeth Leach’s gallery is really good.

There are wonderful Northwest art museums as well. I’ll be going to a SeattleArt Museumexhibit that opens this October, Elles: Women Artists from the Centre Pompidou, Paris. Until August, the Seattle Asian Art Museum has a show called Colors of the Oasis: Central Asian Ikats, which I’ve heard is beautiful. And I’m blown away by the Portland Art Museum. They hold the collection of Clement Greenberg, one of the top art critics in the mid-20th century. Other good places to visit are the Bellevue Art Museum (which is now devoted to craft) and the Museum of Northwest Art (MoNA) in La Conner.

There are also other more alternative spaces that put on shows: Suyama Space, where Seattle’s independent curator Beth Sellers organizes great installations, and A Project Space, a new venue where visitors can view finished pieces as well as art in progress.

NK: Let’s send readers off with an exercise in pithiness. In the last few years, a popular challenge among writers has been to condense their life story into a six-word memoir. Here’s a related challenge to you: What’s your art philosophy in six words?

AK: Delight in experimentation produces palatable results.

More work by Amanda here: http://www.amandaknowles.com/