All of Us Come with a Ballad

By Han VanderHart | Contributing Writer

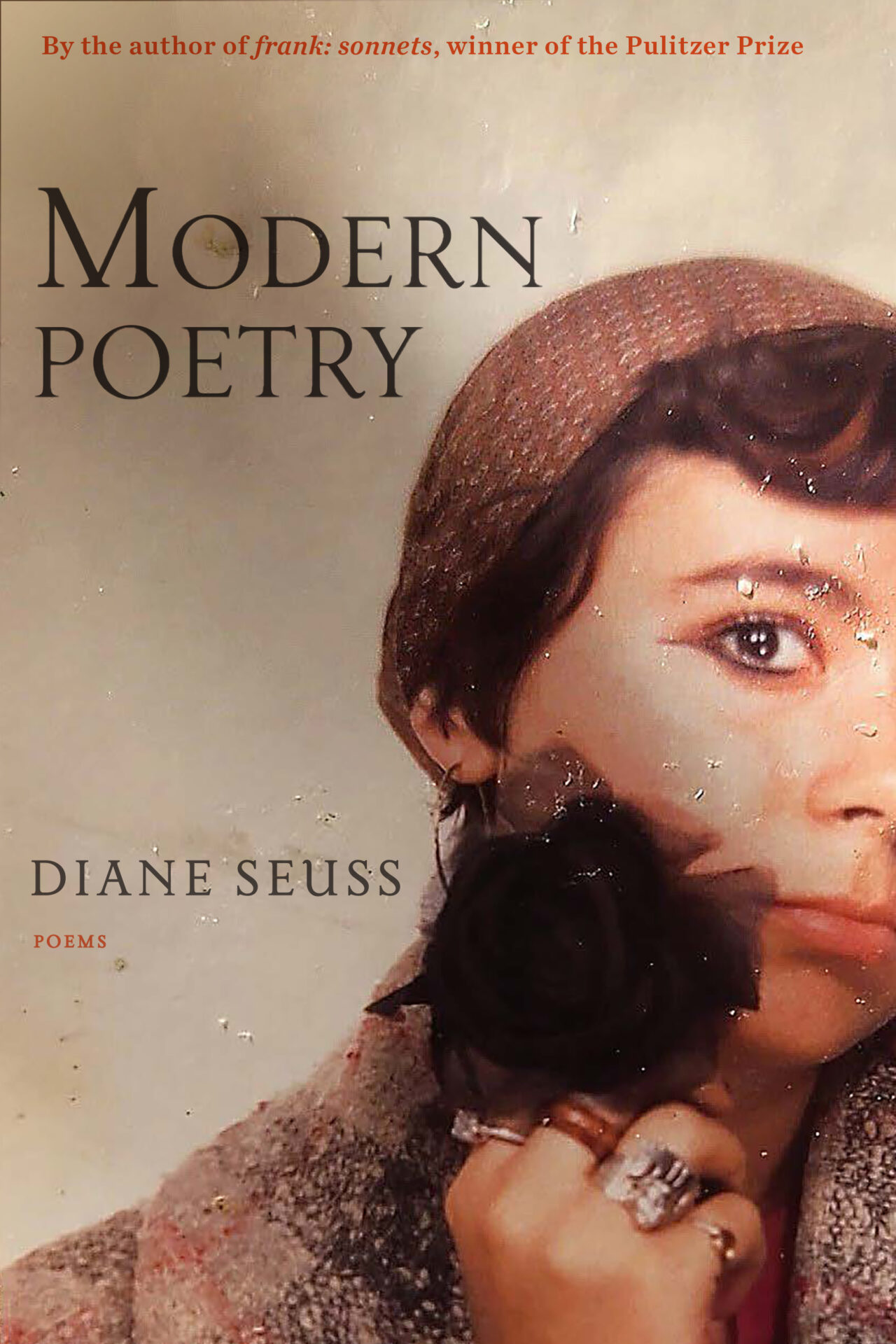

Modern Poetry

By Diane Seuss

Graywolf Press, 2024

The berry bushes are a dream.

The island is a pipe dream.

The pipe is a hallucination.

Still, I’m copious, and so are you.

– Diane Seuss, “Cowpunk”

Diane Seuss’s Modern Poetry has arrived this spring, resplendent in the long, rough-edged stanzas of modernist poetry (“A horse straining at the bit // in the direction of free verse”), even as Seuss dismantles the mythos of modern poetry’s favorite forms and questions the histories of our educations. Tonally, Modern Poetry elicits the lush and decrepit ambiance of the documentary film Grey Gardens: a house overgrown with the foliage of its own garden, filmed in sepia and olive light—the speaker of the poems as moody and arresting a figure as either of the Edith Beales, complete with racoons in the attic. To extend the analogy with the Beales of Grey Gardens a little further: like the mother and daughter living in aged splendor, Modern Poetry is preoccupied with the aging and the modernness of everything, even while maintaining a deep relationship and conversation with the Romantics.

Its title referencing a poetry anthology, Modern Poetry resists the educational privilege ingrained in learning poetry via institutions (the reader thinks instinctively of Ivy League educations, MFA programs, writing residencies abroad), offering instead an account of learning and living with poetry that comes without prestige. In the opening lines of the poem “My Education,” the speaker notes,

Not just what I feel but what I know

and how I know it, my unscholarliness,

my rawness, all rise out of the cobbled

landscape I was born to. Those of you

raised similarly, I want to say: this is not

a detriment and it is not a benefit. It only is,

it is, like a cobbled house is…

For Seuss, writing the self’s narrative and history involves a cool consideration. “My project / was my life,” the speaker observes in “My Education”: “There was no vision or overarching / plan. There was only foraging for supplies . . . .” The speaker’s matter-of-factness and rejection of self-bemoaning calls to readers and writers at the academic fringe, or outside of it altogether: to the working-class writer, to those living outside glittering cultural hubs—to the person awake, listening to the night trains roaring to someplace else. The lines “This is not / a detriment and it is not a benefit” contain a mild sort of comfort (a comfort that jostles nicely next to these lines from Fanny Howe’s London-Rose: “Everyone lacks something in their life. That lack is their life”). Elsewhere in Modern Poetry, as in the poem “Juke,” there is the acknowledgement that limit has its own strange value—or, at least resonance and depth.The poem concludes: “The song choices were limited / so the grooves were dug deep.”

Despite a fascination with Keats—did the speaker in “Romantic Poetry” actually kiss the death mask of Keats in Rome, leaving a red lipstick mark on the chalked visage of the dead poet?—Seuss is uninterested in the abstractions of truth and beauty, and this is a quality to relish in Modern Poetry, which finds its song at the literal ground level in “Weeds”:

What can memory be in these terrible times?

Only instruction. Not a dwelling.Or if you must dwell:

The sweet smell of warm weeds then.

The sweet smell of warm weeds now.

An endurance. A standoff. A rest.

These lines, directing their reader towards a sensual experience of the scent and warmth of weeds (an experience you might have more often as a rural child living lower to the earth), share both a central image and emotional quality with Gerard Manley Hopkins’ sonnet “Spring,” which opens, “When weeds, in wheels, shoot long and lovely and lush; / Thrush’s eggs look little low heavens.” It is the low heavens that catch Seuss’s speaker’s interest most often—the eye-level heavens, the aging dog on the couch. “I have been / in minimal spaces,” recounts the speaker in “Ballad in Sestets”:

Closer to anthill

than cavern or villa. Or tucked inside

the incalculable. A bead swallowed

by a whale,sloughed-off sequin in a warehouse.

A jelly jar, a jar filled with pigs’ feet,

lost in the giant’s pantry.

The figuration of a jar of pigs’ feet brings us close to an account-giving of the poet’s roots, to her geographic and social and class locales, to ruralness, to scrap meats. Seuss’s Modern Poetry—similar to John Murillo’s Kontemporary Amerikan Poetry—burrows into the self’s history, environment, and relationship to power, offering a narrative history that runs counter to the more usual stories of an education in poetry by way of ivory tower. Marianne Moore’s description of “imaginary gardens with real toads in them” seems appropriate for thinking about Seuss’s Modern Poetry, rife as it is with racoons, potato fields, day-old white bread, anti-nostalgia, a desire to give marriage back to the state. “I wish I could tell you how deep / the suck goes,” says the speaker in “Penetralium,” “how dark it is and holy, / its tragedies siloed.” Seuss continues to be a poet who reckons deeply with suffering and deprivation, even while suspicious of such reckoning, and wary of the life-conditions of the that can compel art:

Be drunk . . . it’s the only way, raved

Baudelaire, corkscrewed

through and through with syphilis.

How artless, this source

of art, this shit show where

the greenest

watercress grows.

Anyone who has lived near fields filled with fertilizer in the spring understands where the greenest crops grow. Yet, despite the shit show, the ballad persists—and all of us come with one, assures the poet, even the dog in “Ballad That Ends with Bitch”—“Hers was set in an Amish puppy mill, / Born in a mill, then forced to give birth. / Birth before she’d been a year on this cold earth.” As a poetic form, ballads largely arise from misadventures, not happiness—inspired by that impulse to connect across various human losses, sorrows, revenges. The tradition of the ballad grows from a communal (and common, as in populace) experience of poetry and song—long, varied, sometimes rollicking, sometimes woeful, always entertaining, and usually worth the pause of the average day. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics is quick to point out that ballads are a narrative song shared “among the illiterate or semiliterate,” and the class note is not lost in Seuss’s work. Yet in Modern Poetry, Seuss has come for the ballad as she came for ekphrasis in Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl, and as she came for the sonnet in frank: sonnets —to transform closed poetic forms by sounding a particular, brilliant music through their whorled hollows, by enlivening their very fibers, electrifying the air around them. Seuss’s Modern Poetry is copious, thematically and musically complex, and full of shadowed pleasure. The bitch at the ballad’s close is, after all, poetry herself: “My house is a cold mess except for that thing in the corner. Poetry, / that snarling, flaming bitch.” In Seuss’s many ballad formations, poetry warms the corners of real houses, irrespective of degrees, or family money, or place in the academy.

—

Diane Seuss is the author of six books of poetry, including Modern Poetry; frank: sonnets, winner of the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and the PEN/Voelcker Prize; Still Life With Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize; and Four-Legged Girl, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. She was a 2020 Guggenheim Fellow, and in 2021 she received the John Updike Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She lives in Michigan.

Han VanderHart is a queer writer living in Durham, North Carolina. Their manuscript Larks (Ohio University Press, 2025) received the 2024 Hollis Summers Poetry Prize, judged by Chanda Feldman. Han is the author of the poetry collection What Pecan Light (Bull City Press, 2021) and the chapbook Hands Like Birds (Ethel Zine Press, 2019). They have poetry and essays published in The Boston Globe, Kenyon Review, The American Poetry Review, The Rumpus, AGNI and elsewhere. Han hosts Of Poetry Podcast and co-edits the poetry press River River Books with Amorak Huey.