Afterwords // Pay Attention: Bob Hicok These Days

by Jack Chelgren | Special Projects Intern

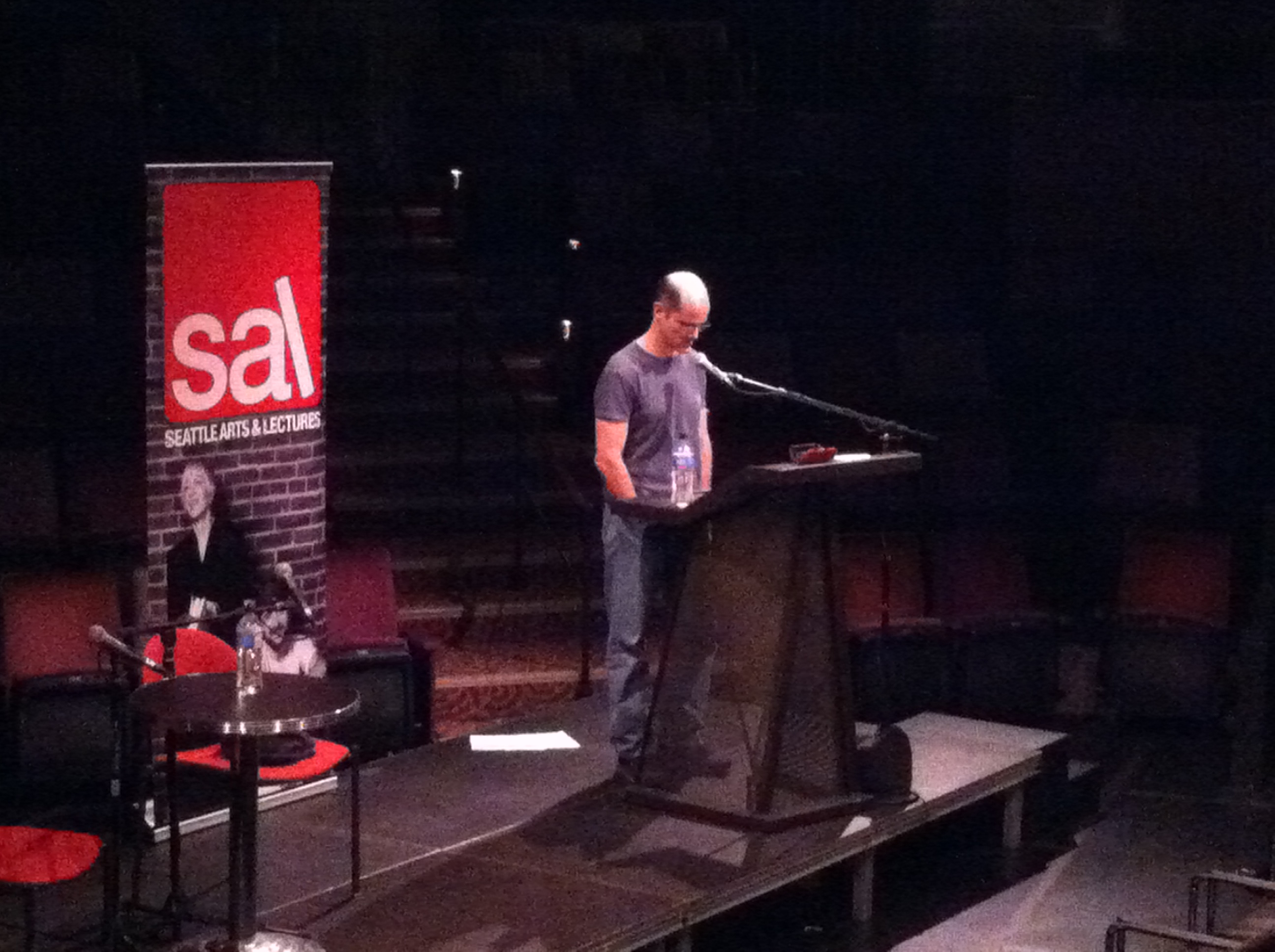

Midway through his reading on Thursday night, part of the Seattle Arts & Lectures 2013-14 Poetry Series, Bob Hicok glanced up at the audience. “Do you really want me to do this for forty minutes?” he asked. “I can’t pay attention at poetry readings.”

People chuckled, but it wasn’t affectation: Hicok seems like the kind of man who has trouble keeping either his mind or his body in one place for very long. Before he came onstage, I saw him squatting in the wings like a leapfrog poised to vault clear of danger. While he read, he frequently balanced on one foot and swiveled around at the podium, or stood a few cautious steps back with both hands jammed in his pockets.

For a man who has published eight successful books of poems, including last year’s Elegy Owed (Copper Canyon Press), and received numerous accolades, including two National Book Award nominations, Hicok is the picture of unpretentiousness. In a voice best described by Judith Wright’s phrase “a flute for the wind’s mouth,” Hicok read poems about love, relationships, family, and soft, respectful sex poems that tease feeling out of mundane scenes and objects, like William Carlos Williams with his heart on his sleeve. The tone of the selections was candid, humble, down-to-earth wisdom. This, perhaps, is Hicok’s preferred mode: in an interview after the reading with SAL Program Director Rebecca Hoogs, Hicok criticized what he perceives as the esoteric, exclusionary character of 20th century poetry from modernism onward. “I think we’ve really seen a professionalization of poetry,” he said, arguing that obscure poems make poetry as a whole seem like an intellectual VIP club. Still, despite this populist ethos and his occasional complaints about the length of his own reading, Hicok made it clear he isn’t interested in sacrificing creativity for accessibility or reader preference. “I don’t give a fuck about the reader,” he said flatly.

The SAL performance showed a different side of Hicok than one finds in Elegy Owed: where the former was forthright and intimate, the latter is rather more newfangled and ironic, a singular concoction of playfulness, imagination, and intense sadness. Although, as its title suggests, Elegy Owed is a collection pervaded by death, it is far from a funeral dirge. Hicok’s approach to the elegy is zany and surprising, swinging from the humorous to the quixotic and then on to the erotic in the space of a few short lines. The book is a mosaic of recurring images, feelings, and gestures: crows, rusty nails, rain, God, poetry, and, of course, death sweep in and out like the bones Hart Crane finds rolling in the tides of “At Melville’s Tomb.” Yet Hicok’s elegies are above all powerful explorations of love, love marked by an acute awareness of loss. The last poem in the collection, “Good-bye,” makes this aspect plain. “I want to be with my wife forever but not as we are,” the speaker tells us. “She’ll become a bear, I a season: Kodiak, spring. // Part of loving bagpipes haunting the gloaming is knowing / the bloodsinging will stop.”

Elegy Owed loses no innovation for its emotional earnestness. The book is replete with attempts to define the indefinite and contain the shapeless, as in “Elegy to unnamed sources,” when the speaker explains, “If you see a man chopping down wind, / it’s me or someone who resembles me, with calluses / and an anchor falling through the ocean of his body.” Here and elsewhere, Hicok succeeds in approximating a nigh irreducible emotional landscape, one of pain, loneliness, and desires that take him beyond the bounds of the possible. Other poems, such as “Listen,” have a vertiginous quality, so much so that reading them feels like stumbling through a zero gravity house of mirrors. Even the most ambitiously strange pieces in the book succeed admirably, among them “Song of the Recital,” a collage of sentence fragments that strikes me as a verse equivalent to John Cage’s work in tape splicing.

Whether delivered onstage or read in a book, the great joy of Hicok’s work lies in its demonstration of what Keats famously called negative capability, the will to abide in contradictions without attempting to resolve them. Hicok’s poems are simultaneously complex and unassuming; they deal in immense personal and ontological dilemmas, but would never use the word “ontological,” nor, I suspect, would they make fun of someone who did. They may be witty, even snarky, but never smug. In their understatement, their modesty, their refusal to supply shoddy answers or false wisdom, Hicok’s poems give us something more meaningful to hold on to: namely, the poems themselves, writing one can return to again and again, each time wondering and marveling about the man “chopping down wind.”

For more information Seattle Arts & Lectures Poetry Series, visit www.lectures.org/