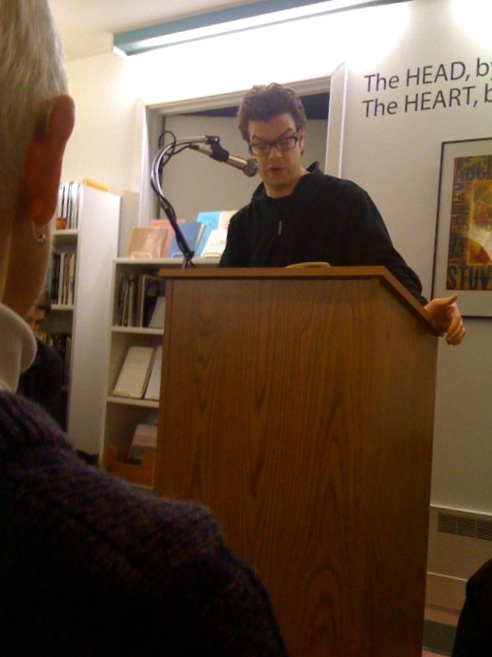

Afterwords // Ben Lerner at Open Books

Friday, January 7, 2010. 7:30 pm

Some of us chugged a beer or cheapy white wine or cash-only whiskey at the Blue Moon before venturing over the I-5 bridge and filtering into Open Books’ long corridor, familiar to most Seattle poetry-lovers, which was packed beyond privacy with bodies and anticipation well before the reading’s start. Co-owner Christine Deavel declared us officially full at 7:25 and shut the door. Her husband and host John Marshall readied the microphone and the woman in front of me said, “I hope this isn’t a night the fire department happens by.”

There was a steady but starving quality to Lerner’s reading voice as he worked his way through the first long section of Mean Free Path (Copper Canyon Press, 2010). “In physics,” he explained, “the ‘mean free path’ of a particle is the average distance it travels before colliding with another particle,” and an audience-member took or tightened a notch on his belt buckle (it’s hard to say). Among the most obvious ways that the poetry interacts with its title and theme is the deliberate lack of sentence completion at the end of a stanza, giving me, among other stomach twists, the feeling that comes when someone says “thank you” when I’ve just said “thank you” and neither of us knows quite what to say next but is racing back over what’s been said already.

The listener, much like an MTA-goer in the Brooklyn Lerner principally writes of, gets lulled into a space between a self and a city, a highly ordered network of associations and sensations driven by his conflagration of high-speed esoteric with the kind of all-day language we spit and mumble, word-strings that he borrows then repeats and then recombines.

The kind of ecstatic sense of being spoken to and of and by simultaneously which was so strongly implied in the work was explicitly referenced in Lerner’s last piece, a new poem called “Rotation.” He spoke of a sort of Whitmanian fantasy in which he is attempting to create the model or ‘I’/eye that is transpersonal, “capable of articulating epic tasks for a population and not just private desires or emotions.” In this poem, the primary characteristics of Lerner’s work come together with a sense of purpose—the repetition of words and images that generate both pattern and surprise become a technique to create the many bodies (eyes, mouths) of a population; the quirk in specificity of similes such as “it’s like smoking with a patch on” is the sort of under-bootsoles intimacy in which the speaker is both himself and everyone else; and the grammatically incomplete sentences (to which I scribbled in my journal during the reading Ben Lerner what are you(,) afraid to finish) becomes a sort of acknowledgement against omnipotence, that this speaker is decidedly not the designer, that he cannot report on endings or future, that he is [merely] the writer of a poem “its figure in slow rotation” in which “each of us carries a volume.”

— EC & KO