Adamant Animal Selfhood

by Alyse Knorr | Contributing Writer

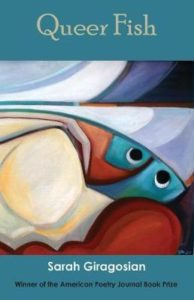

Queer Fish

Queer Fish

Sarah Giragosian

Dream Horse Press, 2017

“You take me back to the woods,” writes Sarah Giragosian in her book Queer Fish, winner of the 2014 American Poetry Journal Book Prize. In her carefully crafted debut collection, Giragosian explores themes of extinction, beauty, and scarcity, pondering animals as small as snails and as giant as colossal squid. In her richly musical poems, Giragosian describes common, rare, mythical, and extinct animals with a care that is both tender and playful. Giragosian’s imagination is luminous, and the intimacy and awe she evokes for creatures of all kinds achieves a spiritual quality. A glass squid is a “genius of minimalism” and tuatara lizards are “as inoculated against time / as angels,” with scales “like ancient mosaic tiles.” Giragosian is especially adept with compound nouns and modifiers that carry the impact of Homeric epithets: a frog has “asparagus-limbs” and a meerkat is a “bandit-eyed” “scorpion-diner.”

These dazzling descriptions of animals are colored throughout the collection by a haunting indictment of the humans destroying them. For instance, in an elegy for beached whales, Giragosian imagines the sound of the whales’ dying songs traveling all the way into a woman’s bathroom as she steps into the tub:

Her brain picks up

the accent of a dying tongue,amplified by the tub’s dimensions,

but far too distant

and visceral for translation.

In another piece, Giragosian adopts the voice of a grieving, dying horseshoe crab as it utters its last words:

We are all poison and poisoned, slick with oil

and its rings of dark pearl […]

Everywhere along the shore we cry for love

and the sweeping arms of a green sea.

Though the “we” here is ostensibly the gulls, jellyfish, and starfish surrounding the crab on the beach, it easily takes on the weight of a collective human lament.

Giragosian wields a number of different eco-poetic approaches in this collection. In some poems, the speaker imagines herself as an animal; in others, Giragosian anthropomorphizes her animal subjects. She never over-romanticizes them, however, and she makes clear the line between human and animal worlds. For instance, in “The Lioness,” Giragosian unfolds a narrative in which, after an attack, a lioness seems at first to be comforting or bathing her dying cub. The poem turns when Giragosian reveals that the lioness is actually eating her cub’s corpse. If there’s a moral in this story, it’s a positive one:

In the economies of death,

let there be no waste,

and if there is a witness overhead,

let my body’s strange devotions deter him.

Some of the most powerful poems operate through the lyric address. For instance, “Lonesome George” addresses the last member of a certain species of tortoise. The poem reads as a sort of apology, and an incrimination of the humans responsible for George’s extinction:

[…] no animal goes unmolested on this earth,

and to be the last is to suffer idolatry

or worse, this mortal irony:

the zoo plans to embalm you

Here and in several other poems, Giragosian is critical of the ways that animal preservation only occurs after death and extinction, in museum displays and elegiac art. “The Last Animal” takes this criticism to its extremes and reads in all the best ways like W.S. Merwin’s “For a Coming Extinction”:

When we kill, we do it well.

I have paid to see their bones

encased in glass[…]I’ve stroked

the memory of tortoise

in concrete parks, and loitered in halls

of heads and thrusting torsos.

Art, too, can serve as a kind of false preservation too easily distanced from actual life—a distance that animals themselves resist. For instance, “Ars Poetica” describes a photographer’s attempt to photograph a damselfly swerving through the air. Just as the artist is about to “intercept” the creature and take the photo, the damselfly takes off again, “resist[ing]” the artist’s eye and “flourishing // her gift for evasion.”

Through both the scientific and artistic human Gaze, Giragosian argues, animals are commodified and put on display in zoos, museums, art galleries, and even poems. The well-crafted dioramas we make of animal bodies and fossils, Giragosian contends, are no different from poems that use animals as a means to a human end. Giragosian’s poems are self-aware and do not shy from self-implicating:

Meanwhile, the poet, intent to capture

the beast, retreats in smile

and costumery to bare

the ostrich to the man,

Perhaps the most chilling examination of this theme occurs in “Mummified Baboon, Unburied,” which adopts the voice of the baboon and begins, “When they come for me, they come with shovels, / augers and picks.” The exhumed baboon is catalogued and locked in a glass case for children to peer inside. But Giragosian asks: what happens to the animal’s soul? Such creatures are “not received, but not forsaken.” When the acts of science and art-making turn voyeuristic, Giragosian reminds us,

[w]e strip the trees of music,

we miss the flowers, we forget

that metaphor is molecular.

As the book progresses, Giragosian ties violence against animals to racism and gendered violence; for instance, “Leda” describes Leda’s rape from Leda’s perspective, denying the tale any romanticization of Zeus as an elegant swan. “Easter Dinner,” a striking eco-feminist poem in the middle of the book, recalls Maxine Kumin’s “The Whole Hog” in its frank take on meat-eating. In this poem, Giragosian imagines a family gathered around a roast at the dinner table. In a series of imagery that evokes gendered violence, the husband carves up the meat, which he prefers to be

soft as an ear lobe,

the wings and face avulsed from the body,

all traces of her life and death

dismembered from the table.

Then, in the next stanza, Giragosian makes her startling turn:

Someone could recall the bird before

when she nipped ice crystals out of her wings

and sunbathed at dawn. Or someone

might speak of how she sang her horror through blood

when they shackled her legs,

hung her upside down, and slit her throat,

cutting her head clean off. But no one does.

The gendered violence theme continues at the conclusion of the poem, when Giragosian writes that the husband will “colonize” a living room chair while his wife “clear[s] the carnage from the table.”

Giragosian is a scholar of Moore and Bishop, and the influences show in her approaches to tone and description. For example, a conversation between speaker and seals in “The Seals Off the Coast of Manomet” recalls a similar human-seal interaction in Bishop’s “At the Fishhouses.” In Giragosian’s scene, the seals

speak with an inquisitive inflection

as if to ask, How does this relate

to what we were talking about?

In this humorous poem and in “Classifieds: Missed Connections,” Giragosian reminds us that contact with animals isn’t always miraculous or rhapsodic. This tonal range, which can easily travel from humorous to tragic to romantic, is one of Giragosian’s greatest strengths.

Again and again in Queer Fish, as indicated by the title, Giragosian blurs the boundary between humans and animals. Many poems reference the liminal spaces of sleep and dreams, and her frequent gestures toward mirroring and reflection work to queer the gaze and the body in non-hegemonic ways. For instance, in “What I Mean When I Say I Knew You Long Before We Met,” the girl lovers become horse-like, “gallop[ing]” and “buck[ing] through screen doors / and vault[ing] out of windows”:

Our bodies then were porous

and promiscuous. We were woodland creatures,

hardly people, and we felt no shame

in small indiscretions. Even being a boy was easy,

nothing more than moulting off a shirt

and uncovering our flat chests.

These queer transformations exemplify Giragosian’s fluid approach to both gender and species. If queer ecology seeks to re-define what is “normal” and “natural,” then Giragosian’s poems extend that argument to build an adamant animal selfhood.

Alyse Knorr is an assistant professor of English at Regis University and editor of Switchback Books. She is the author of the poetry collections Mega-City Redux (Green Mountains Review, 2017), Copper Mother (