A Small Dislocation

by Devin Kelly | Contributing Writer

The hardest part about watching my grandmother die was watching my grandmother die. I remember sitting with my father and aunt at the kitchen table in a room that forever seems yellow a month before my grandmother passed away, watching as the spoon of peas she held trembled. We said what we needed to say. Eat, we said, you need to. I remember how she lowered her head then, so far away from being a child, and let out something just barely a whisper. I’m so scared, she said.

Her kidneys failed not long after. She was 96, suffering mostly from the complications of age. She lived long enough to be considered lucky for living long enough. What she lacked in those last months is what we all lack—the ability to make sense of what she would never know until it happened and, because of such happening, carried her away from us, into whatever world—impossible to describe and perhaps impossible to even be known—exists beyond this one. She lacked one more thing: the language to articulate this forever-unknowing.

In his poem, “Dear Stranger Extant in Memory by the Blue Juniata,” from The Book of Nightmares, Galway Kinnell writes, “the dream / of all poems / and the text / of all loves—‘Tenderness toward Existence.’” These lines serve as a hopeful thesis of the book, which is rife with lyric fear. “Listen, Kinnell,” the poem “The Hen Flower” asserts, before moving to the conclusion: “even these feathers freed from their wings forever / are afraid.” That same poem’s first stanza includes the pained hope: “if only / we could let go / like her, throw ourselves / on the mercy of darkness . . .”

Written in 1971, when Kinnell was 44 and unknowingly 43 years away from death, The Book of Nightmares is a feverish yet tender study of the fear of death, that very human anxiety steeped in the unknown. Each time I read it in the years after my grandmother’s passing, I think of the lines from “The Hen Flower,” where the poem speaks toward the “wing / made only to fly,” the wing “unable / to write out the sorrows of being unable / to hold another in one’s arms.” Kinnell’s poetry in The Book of Nightmares is so much a poetry of life, a poetry that is tender toward existence. Death, in this equation, is not existence. It is feared. It is a lack, a loss of life, a place of being unable to write out sorrow. Unable to fly.

Written in 1971, when Kinnell was 44 and unknowingly 43 years away from death, The Book of Nightmares is a feverish yet tender study of the fear of death, that very human anxiety steeped in the unknown.

When I think of those lines, however, I think of my grandmother in those months before dying. A Hungarian woman of deep faith and few words, she could not articulate that knowledge of being so close to death—and all such a space might entail, be it fear, or acceptance, or whatever else—with language. Her language in those last months was reduced to few words—I’m so scared—and the small, substantial actions that accompanied those words. The hanging of a head. The shaking of a spoon. She was a person “unable / to write out the sorrows of being unable.”

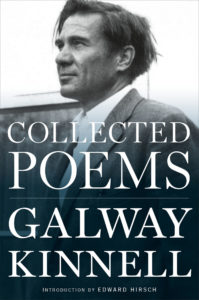

I think, though, that one of the poet’s jobs—of many—is to dwell in the space of forever-unknowing, not with the intent to seek an answer, but to allow oneself better ways of understanding mystery and wonder. The poet does not give us answers. The poet gives us new ways to live and see and love without answers. When I read Kinnell’s work, I feel that deeply. But I am also interested in the ways Kinnell moved toward death rather than away from it, especially as he aged. As you read more deeply into Kinnell’s progression over the years as a poet, which is made possible by the relatively newly released Collected Poems, you come to see a poet whose tenderness is not simply turned toward existence, but turned as well toward death.

Kinnell’s next book, Mortal Acts, Mortal Words, begins a growing tenderness toward death that The Book of Nightmares suggested but never directly stated. It’s not fully formed, but it’s there. One poem, “Fisherman,” written for Allen Planz, begins that turn away from life: “I know ordinary life was hard / and worry joined your brains’ faces in pure, baffled lines, / and therefore some part of you will have gone / with her, imprinted now / into that world that she alone doesn’t fear / and that now you have to that degree also ceased fearing.” Each literal turn, each breaking line, complicates life and solidifies the certainty of death. Life is hard, and then worrisome, and then there is the leaving that comes with fear, and then the absence of fear that comes with coming close to certainty. The poem is a face turning in stunted, scene-like motions.

Here too, you have the counter to that phrase tenderness toward existence. What if life is hard, and death—still unknown—manages to grow less fearful? What then?

As the book progresses and begins to bear witness to Kinnell’s mother dying, Kinnell enacts a certain work of gazing at death without retreating back toward life. In the short simile of a poem, “Looking at Your Face,” Kinnell describes the impossibility of writing about death: “Looking at your face / now you have become ready to die / is like kneeling at an old gravestone / on an afternoon without sun, / trying to read / the white chiselings of the poem / in the white stone.” It is, above anything, a poem of despair, of trying, of inability. But, beyond that, the poem is grounded in the image of the poet at work, despite uncertainty. There is the poet kneeling. There is the poet understanding the impossibility of the task, the white words on the white stone in a contrast-less world without light. And still, the looking. Always the looking. Here, it seems, Kinnell begins to believe in tenderness as an act of holding—a gaze, a hand, a complexity.

Kinnell enacts a certain work of gazing at death without retreating back toward life.

This is not to say that The Book of Nightmares was lacking in complexity, but simply to say that Kinnell’s progression away from that book offered a new kind of dwelling in something even more intricate, one that tried to turn between two things at once: existence and its absence. Later in Mortal Acts, Mortal Words, Kinnell writes, “The one who holds still and looks out, / alone / of all of us, may die mostly of happiness.” The insertion of the word “mostly” implies an assertion that is at once beautiful and terrifying. To die of happiness alone seems impossible. But looking out, holding still, refusing to turn—these things can make it almost possible.

I don’t know what it would be like to die of happiness, to die mostly of happiness, or to die at all. But I know that looking can be hard and holding still can be hard and doing both at once—in this world of all worlds—can be a feat. One of the privileges of reading someone like Kinnell is the result of his privilege, a privilege that allowed him to grow old, stay relatively healthy, and have the security to write. It is a privilege for us because we get to see how holding still and looking—one of many definitions of a poet—can translate over the years.

For example, in his next book, The Past, written in 1985, Kinnell begins with the poem “The Road Between Here and There.” Abandoning narrative for a litany of images, the poem cycles through an array of moments transcendent in their simplicity. The poet “blessed-speeding” down the highway to see his kids before sleep. A burlap sack with two rescued piglets rustling inside of it “like pregnancy itself.” It reads like a Ross Gay or Maurice Manning-esque celebration of nature, family life, and wonder, before ending, “For when the spaces along the road between here and there are all used up, that’s it.”

This is what I mean when I consider the privilege of reading a poet having the privilege of writing into old age. Fourteen years prior to this line, Kinnell authored an entire book dedicated to the fearful yet tender anxiety of death, and here, he begins another book with death’s calm acceptance—“that’s it”—at its forefront. This calm acceptance becomes, it seems, a touchstone for his poetry as it progresses onward.

There’s a line in “The Tragedy of Bricks,” the first poem from Kinnell’s 1985 book, When One Has Lived a Long Time Alone (perhaps my favorite of his), which includes a similar calm acceptance to that in “The Road Between Here and There”—“Suddenly the full moon / lays out across the imperfect world / everything’s grave.” Kinnell breaks the line immediately after world to let those words—“everything’s grave”—sit alone. It’s a beautiful and sorrowful double meaning, implying both the inherent solemnity and sadness of all that is alive, and the simple fact that everything—including the living—is a kind of grave.

Sixty-one at the time of this writing, Kinnell’s calm, if stern, acceptance of death begins, at this point, to add definition to all else around it. Later, in the poem “Shooting Stars,” he writes, referring to the stars, “Last night, / deaths up there more brilliant / than lives.” It’s an obvious metaphor, made all too often, that up there, so much of what we see is already dead, and shining because of such death. But with Kinnell, it feels like a shift in the way he views the world. A few lines later, he writes of being born as “the hard labor / of dying.” Perhaps here, in ever increasing age, Kinnell is realizing how fluid the existence in the phrase tenderness toward existence is, how in dying there remains a kind of life, how in birth there exists a kind of dying.

This realization, on Kinnell’s part and on the part of all who have realized or continue to realize it, takes great courage. It makes an acknowledgement up front: that death is another one of life’s open doors, rather than the door that shuts off life. It is a turning into rather than a turning from. I wish, sometimes, that I could’ve said that to my grandmother. I didn’t have the courage. Not to say something about turning, not to convince her to think differently of death, but to hold her hand and say, simply, calmly, it’s okay, grandma, I’ll be there soon. That statement, which embodies the movement of Kinnell’s later poetry, is true on all fronts: wherever there is, we’ll all be there soon. And perhaps we will be as brilliant as stars. That, regardless of belief, feels a great comfort, and it takes, no matter who you are, great courage to say.

So much of this comes to a fuller realization in a few poems of Imperfect Thirst, published four years later. In fact, Kinnell even defines death in his poem, “Parkinson’s Disease,” which ends, “it will be only a small dislocation / for him to pass from this paradise into the next.” Later, in “The Striped Snake and the Goldfinch,” he writes, “Yet I know more than ever that here is the true place.” What’s fascinating is the way both of these poems are borne out of pain—the first details the long pain of witnessing Parkinson’s, and the second is, among other things, a meandering elegy to still living while so much else has gone—and yet both poems find both in death and this world a “paradise” or “true place.”

I think of that phrase—“a small dislocation”—a great deal, mostly because it runs contrary to every definition of death, poetic or otherwise, I’ve come to witness, whether a new life, an eternal transformation, or a great nothing. A small dislocation is a minor thing, like moving from one floor to another, giving up your bus seat for someone else. It holds no terror, and that is what I keep returning to as I consider Kinnell’s later work. Mostly because I can still see my grandmother trembling. I can still see my father stepping out the funeral director’s office to cry. I can see the table he left, and the dollar-figure amount circled on a piece of paper there.

One of the great pains of life is that we, especially in the Western, deeply capitalistic world, have done nothing to make death seem like a “small dislocation.”

One of the great pains of life is that we, especially in the Western, deeply capitalistic world, have done nothing to make death seem like a “small dislocation.” In fact, the pains of this world make it such that sometimes life is the opposite of paradise, and the dislocation death offers is great, and better. I think poetry, though, especially Kinnell’s, can do the hard work of turning our gaze from death to life and back, and, in doing so, tenderizing mystery into something beautiful. Death for Kinnell, especially as he ages, is no more than a volta. It is one line gracefully paring itself off, hanging there, and being turned into the next. It is so small it fits on a page.

Return to that poem “The Hen Flower” and see how Kinnell addresses himself. “Listen, Kinnell,” he writes, before wondering if it’s possible to throw himself on the “mercy of darkness.” 23 years later, in the collection of ghazals that makes up its own section of Imperfect Thirst, he addresses himself again, this time by his first name. “Not many are able to die well, not even Jesus going back to his father,” he writes, before imagining a man seeing an owl taking flight. “Galway…” he writes, “it is you being accepted back into the family of / mortals.” These ghazals, each ending with an address to himself, no longer have that same rough insistence and hope contained within The Book of Nightmares. In fact, the ending of “Paradise Elsewhere” seems to even reach back to that older book and acknowledge that old fear: “Yet it has happened to many others, and to you, too, Galway—when / illness, or unhappiness, or imagining the future wears an empty / place inside us, the idea of paradise elsewhere quickly fills it.”

By the time Kinnell’s last collection, Strong Is Your Hold, was published in 2006, when Kinnell was nearly 80, Kinnell’s relationship with death carries with it everything that once marked his poetry’s relationship with life: joy, wit, courage, tenderness, compassion. Notice the steadfast sureness of the poem “Promissory Note,” which opens with the lines, “If I die before you / which is all but certain . . .”

Juxtapose that opening with the opening of the poem “Pure Balance,” which begins: “Wherever we are is unlikely.” Less fearful of death than certain of it, Kinnell’s poetry still dwells in the unanswerable-ness of life, the wonder, and, as he writes later in that same poem, the exhilaration: “Neither do I understand why it’s / exhilarating—as well as the other things it is—/ to know one doesn’t have a future, / or how much longer one won’t have one.” If anything, Kinnell’s poetry here can show us that the cup of trembling—an image of suffering, pain, and insecurity from the Book of Isaiah—doesn’t always have to be lifted from our hands, that, in fact, unease can be lived with, and perhaps must be lived with, if anything that might assemble itself toward joy could ever possibly be found. What I love about Kinnell’s work is that the tenderness in these moments is a kind of reaching-through-the-page, an easy, gentle comfort. With his certainty of death comes an increased compassion. I read his poetry to give myself permission to find in both life’s unanswerable questions and life’s certain ends a solid and generous joy. Then I put the book down and try to live that joy.

In “Last Poems,” the appropriately-titled final section of his newly released Collected Poems, Kinnell reaches a moment in his poetry where, after turning away from death, and then, later, turning back toward it, he finally arrives as asymptotically-close as he can to the face of it. Indeed, the collected poems that preface that final section are riddled with elegies for poets and friends lost, and the final section serves as an elegy to everything Kinnell knows he might leave behind.

In “Astonishment,” Kinnell writes, “Our time seems to be up—I think I even hear it stopping.” This volta-like moment turns drastically into the next line, which might serve as one of the truest questions of poetry: “Then why have we kept up the singing so long?” Good lord, Galway. What other question is there?

And this, I think, is one of the most important points I’ve learned from Kinnell’s later work, that comfort, or acceptance, or even joy—if you can call it any of these—must, if found, be shared.

One gets the sense, however, that this is not a question borne of cynicism or despair, but rather a kind of incredulous and tender hope. Indeed, he answers the question, writing, “Because that’s the sort of determined creature we are.” The choice there, to speak in the plural instead of the singular, to include the wide berth of humanity in this gorgeous recognition of its strength, is the mark of a poet aging into generosity and not hoarding epiphany for the singular self. And this, I think, is one of the most important points I’ve learned from Kinnell’s later work, that comfort, or acceptance, or even joy—if you can call it any of these—must, if found, be shared. The “we” here in this near-final poem is a collective thank you to all, it seems, to whom Kinnell owes a debt, simply for being alive.

The final poems of Kinnell’s Collected Poems are the poems I spend the most time with, mostly because they enact a graceful trend toward childlike wonder. It is the certainty of death, its nearing, looming presence, that gives not an urgency, as one might imagine, but a single certainty from which the rest of life and all of its unanswered questions seem not like a failure, but a journey. I think of one of Zeno’s paradoxes, that, in order to arrive somewhere, one must forever-pass halfway between one point and the next, like a child trying to fold a piece of paper into infinitely smaller squares. Kinnell’s final poems are poised somewhere further out along the infinite, further away from where he began but no closer to arriving at an answer. They linger beautifully there. I see the child holding the paper, grinning with the task that lies ahead. I see my grandmother holding the trembling spoon. I see myself reaching to hold it with her.

—

Devin Kelly is the author of In This Quiet Church of Night, I Say Amen (Civil Coping Mechanisms) and the co-host of the Dead Rabbits Reading Series. He is the winner of a Best of the Net Prize, and his writing has appeared or is forthcoming in The Guardian, LitHub, Catapult, DIAGRAM, Redivider, and more. He lives and teaches high school in New York City.