A Condition of Being Transformed

By Amanda Auerbach | Contributing Writer

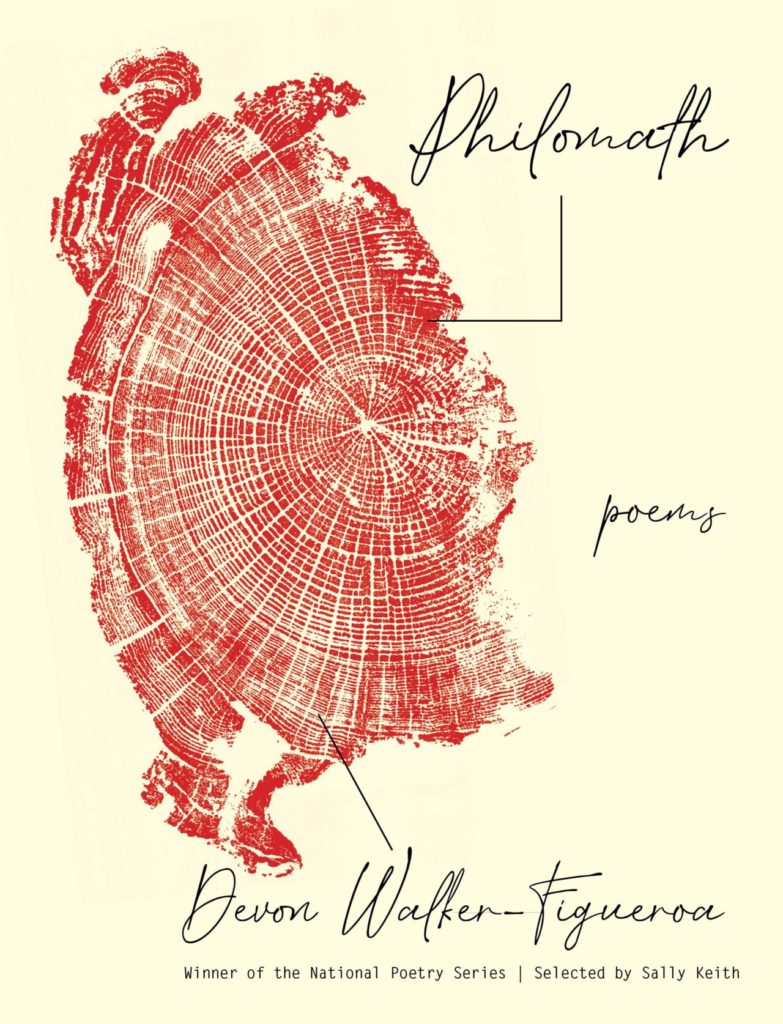

Philomath: Poems

Devon Walker-Figueroa

Milkweed Editions, 2021

Devon Walker-Figueroa’s Philomath, a winner of the 2021 National Poetry Series, is named after a town close to where the speaker grew up. Philomath itself stands in as the general geographic location in which the speaker first learns what it means to live in a house, to be in a family, to be educated, to be stung by wasps, to have a name and a body, to practice a religion, and to have friends. Walker-Figueroa’s collection does not treat rootedness as a limitation that might be overcome by taking a broader perspective. Instead, her idea is that a person can be shaped by a particular place, and that place becomes the condition for knowing anything about this life. Believing in the power of location to act as a source of important instructions is a condition of being transformed.

The primary lesson of Philomath is that one cannot be saved, but is stuck on this earth and in one’s self and perhaps in Philomath. The first poem in Philomath, “Philomath,” introduces the religious stakes of this lesson:

Megan & I go to Vacation

Bible School & sing about going “straight

to heaven or down the hole,” where the pastor slips

nylons over our faces & tells us to suck

pudding from a bucket just to show how far we’ll go

to be forgiven. We swallow it all

because this is how you get close

to God in Philomath.

Those who suck pudding through nylons do so in order to be saved, but in doing it, they go into the hole that is hell. This punishment teaches the children that what salvation means in Philomath is not escape, but choice: to descend further into the hole in which one has been placed. Such a lesson, when imposed against a person’s will, is a means of punishment, of putting that person in her place as “when Megan’s dad learns / she’s saved & he’s not, he teaches her / a lesson about being sorry & how God is not.”

But Philomath is not just a town, it’s also a word that means “lover of learning.” First, there is the name into which she has been placed by her parents, which is the first word she learns to write. In the book’s second poem, “Permission to Mar,” the speaker describes the experience:

Outside the house is the sound of becoming—

the chirr of locusts, their low-

lying electricity in the field, their inhuman

hum accelerating into

a revision of silence. Inside, I write

my name, the only one whose characters I know

por corazón, and just by half—my last

still incomprehensible, on the wall. All

jagged and majuscular, all orange story-

book shade of flame, inconstant color I

learn with lightpressure behind the crayon’s tip.

The hell of the previous poem appears here in the storybook flame shade of a crayon. This act of learning one’s place in the world (as a person with a certain name) merges the singeing with the pleasurable. The perfect instrument for the lesson is therefore the crayon, which must be pressed lightly behind the tip in order to work, and which makes vivid marks on the wall.

Philomath can be seen as a place in which the speaker has experiences which she must continue to inhabit until they reveal their underlying nature in the visually and rhythmically arranged language of poetry. This becomes clear in “Out of Body,” in which the speaker’s father burns her deceased mother’s possessions:

think of the fuelhow it exists

to push the heat backinto my mother’s chairhow the light climbs

each rung

the flame seemingto wantup and out of its own

need to consumewhat frames the light of its own unmaking

breath in the ashchest

chair

facesnobigger than

fingerprintsflame-lickedarmsfeet

auburncurls

whatthe air cannot hold

it leaves on the tongue.

You can see that the second line of the portion I included above gets pushed back into the margin like the heat does into the speaker’s mother’s chair, and that the spaces among the fragments seem to become flame-licked like the rungs. In this way, the words of the poem become the objects the flames cannot consume, they become that which remains on the tongue. One consistently gets the feeling in reading Walker-Figueroa’s poems that the only words allowed to remain are those that must be there. Just as those whose lives reveal the nature of Philomath are consigned to remain there, the same might be said of the words of these poems.

Each poem can thus be seen as a location at which the durable remains of an experience can continue to live on. But there are other experiences that reveal a place in the self that is always there, but which is not always activated. Poems can activate these private, preexisting locations. One such place is the location of one’s capacity to access the sacred. Walker-Figueroa refers to this part of the self in “My Materia,” in which figures a group of young girls including her mother:

one way, another, theirloose robes shimmering as they shuffle to

and to and fro, their frayed

attempt at symmetry, in order that the sacred takeshape, in order

that the taken daughters, wife, health, merciful

maker could livein the sacrament of the mind

a little longer (the hymn that is being

forgotten begins Be Thou.

Forming a cross thus creates for the girls an experience of the sacred that proves that capacity in the self, which might be called the soul. In “Ascent,” the speaker is taught by her sister to access a part of the self that is “down by the creek / named for its sweat- / scented roots.” The yonic image corresponds to the part of the self that is receptive to sexual release. Private sexual experience also reveals the nature of the creek and the instruction it can offer to human beings.

The soul is elusive and so too is the sexually responsive part of the self. Likewise elusive is the part of the self that is activated by a particular sonic landscape. The final poem, “Gallowed Be,” is characterized by long vowel sounds that form valleys for wallowing. These long vowel sounds include blended vowels like the “al” in “valley” and “fallowing”:

the neighbor’s piglets wallow

in their loam. (Still,

the world iswide, if the hymnal’s hold

true,& every beast has a mindto get loose

from a valley fallowing

toward foul.) My sisterbraids my waist-

length mane, says, “this

place islame.” I try to tell her

no one is to blame, but the sky is

so hollow it swallows every name.

The speaker suggests that the place itself, Philomath, which physically corresponds to the poem’s sonic landscape, is ultimately “to blame” for these poems. If that is true, then the part of the self that finds its expression in those sounds is also to blame. Walker-Figueroa’s Philomath offers the reader a richly detailed town, abundant in lore. Philomath is a place in which one gets stuck in ways that are instructive. Such places also include stories, and poems.

—

Amanda Auerbach is a poet and literary critic. Her book of poems What Need Have We For Such as We was published by C&R Press in 2019. Her poems have also appeared in Poetry Northwest, the Paris Review, and Kenyon Review. She teaches literature and creative writing at Catholic University in Washington D.C.

Devon Walker-Figueroa is the author of Philomath, selected for the 2020 National Poetry Series by Sally Keith. She is a writer, editor, and creative writing instructor who grew up in Kings Valley, a ghost town in the Oregon Coast Range. A graduate of Bennington College and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Walker-Figueroa has published work in such journals as the American Poetry Review, The Nation, POETRY, Poets & Writers, Lana Turner, The Harvard Advocate, Ploughshares, and the New England Review. Devon is the recipient of the New England Review’s Emerging Writer Award, University of Iowa’s Donald Justice Poetry Prize, and the Jill Davis Fellowship at NYU, where she currently teaches undergraduate creative writing courses.