A Braided Stream: On Keats Conley’s Guidance from the God of Seahorses

Paul Lindholdt | Contributing Writer

What science does is what I would like more literature to do too:

Helen Macdonald, Vesper Flights

show us that we are living in a world that is not all about us.

Guidance from the God of Seahorses

Keats Conley

Green Writers Press, 2021

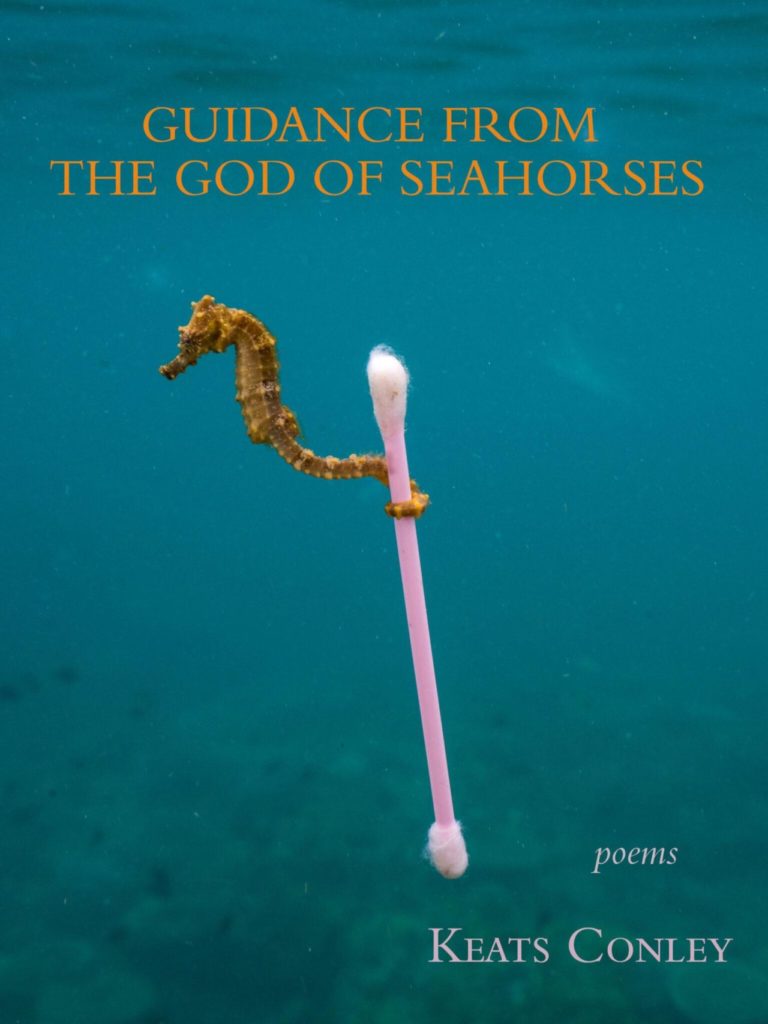

The cover of Keats Conley’s Guidance from the God of Seahorses features a photograph, one that went viral in 2016, of a seahorse whose tail encircles a pink Q-tip. That seahorse, a seemingly posthuman image, appears to be considering the Q-tip as a mate. Marine biologist Justin Hofman snapped the photo off the Indonesian island of Sumbawa, and the photo has come to stand as unforgettable evidence of marine trash. Plastic everywhere breaks down into tiny bits, known as microplastics, which swirl deep in the seas and are borne by breezes high atop mountain peaks.

Keats Conley, who is herself a marine biologist, told interviewer Mel Ruth in the literary journal Arkana that she conceived the poems in Guidance from the God of Seahorses as a series of statements made by the gods about the sixth extinction bearing down on the natural world. The gods of some poems address their tributary animals directly; other poems read like panoptic commentaries on the randomness of the evolutionary process.

In the lyrical “God of Coyotes,” the reader meets a god who created coyotes “from the shadow of a cumulus cloud, straying over open plains.” The god directs the coyote: “Drink tea made of corn silk and shelter yourself in the husks.”

The voice of “God of Mosquitos” is declarative and explanatory: “I pulled your wings from water to intrude upon silence like a violin.” Mosquitoes hatch from eggs dropped in brackish water, and their wings whine like tiny violins.

The New England Transcendentalists believed that enlightened humans take part in divine creation. Enlightenment is the kicker and the key. Ralph Waldo Emerson defined the unenlightened human as “a god in ruins.” In these poems, Keats Conley intimates that scientific knowledge can stimulate spiritual illumination.

One of her gods notes—of the coconut octopus—“We measure intelligence by the manipulation of objects—to open a jar and dissolve in it.” Octopuses have been documented performing that feat. In these poems, humans are not the only makers and creators. In “The God of Beavers,” the speaker enlightens its tributary animal: “I made you a mover. A shaker of landscapes.” The beaver, its god declares, is “a fellow ecosmith.”

The word inspiration, related to respiration, traces etymologically to “god’s breath.” A god may breathe upon the human subject and confer a lively inspiration. Such divine afflatus luffs the sails of artistic creation. But even the gods have lessons to learn, as the ancient Greeks knew.

“The God of Greater Sage-Grouse” opens, “Here in the sagebrush steppe is where I learned to breathe—here in this landscape like a clear idea.” Sage grouse booming on mating grounds, or leks, know that breath is a key to their survival. “Tilt back your head,” the god directs that grouse. “Inflate the skin of your gular sacs. Devour the air and then set it free.”

Chronicling a madcap bit of natural history, “The God of Galapagos Tortoises” opens with this sentence: “Your saddleback was the ashram for Darwin’s first tree pose.” The tree pose in yoga is a one-legged upright stance like that of storks and herons. In 1835, Charles Darwin dined on Galapagos tortoises. They weighed up to eight hundred pounds. He also tried to ride them.

Conley’s book, to adopt a phrase of her own making, functions like an “earworm for the Anthropocene.” That is, these poems resound in a chorus about the present geological epoch named after our own kind. This poet’s gift for figurative language is surefire throughout.

“The God of Bison” announces to its mammalian creation, “I shaped the soil around your cloven toes, and from your hoofprint sprang the stubble of bluestem—my favorite five o’clock shadow.” That image alludes to research that shows those massive bovines—their hooves like organic tractors—plowed the prairies. In another memorable figure of speech, the wary cougar may be seen, if it is seen at all, “weaving through the landscape like a braided stream.” And, just as evolution works by random acts of creation, many of whose acts result in failure, “watercolor is the most unforgiving medium—hard to control, harder to erase, easy to overdo.”

Readers of this book may trace the scientific references, along with the poems’ rich figures and sonics, as components of an integrated whole.

—

Keats Conley is the author of the poetry collection Guidance from the God of Seahorses (Green Writers Press, 2021). She earned a PhD in marine biology from the University of Oregon. She has conducted marine research around the world, and has been published in scientific journals such as Nature Microbiology, PLOS One, and Limnology and Oceanography. Conley is currently a fish biologist in Idaho, where her work centers on threatened and endangered species. She enjoys writing poetry as a means of sharing science with a broader audience, particularly to help cultivate a sense of urgency about global biodiversity loss.

Paul Lindholdt, an English professor at Eastern Washington University, has written Making Landfall: Poems (Encircle Publications, 2018) and Interrogating Travel (LSU Press, 2023).