by Meryl Natchez | Contributing Writer

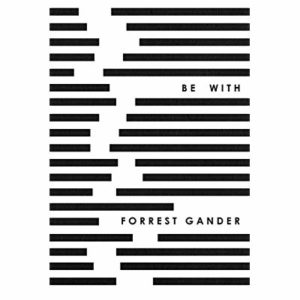

Be With, Forrest Gander’s first new book of original poetry in five years, is an extraordinary journey through a difficult period, one during which he has been working to reassemble his life after the sudden loss of his wife, the poet C. D. Wright. It is also a time during which he is dealing with the increasing confusion of his aging mother. These themes echo through the book in lush and surprising language. I interviewed Gander in Petaluma, California, shortly before he departed for India to take part in the first Indian Ceramics Triennale, where he presented a collaborative installation of ceramics and poetry with Ashwini Bhat.

I know you are about to set off for India tomorrow, and in this book, as in past work, travel and landscape are integral to your work. What motivates your travel?

I spoke about this a bit in Core Samples. Here’s the quote: “I was looking for bonds. I wanted to break a mirror. I wanted to render myself accessible, available. I wanted to borrow eyes from another language. I was looking for the words to come.” This is still a good description of why I travel.

Yes, I love that description in Core Samples, and also the way the travels are all in the present tense, which makes the experience so alive for the reader. What struck me about this book, Be With—obviously there is a lot of pain in it, but there is a complete absence of sentimentality. You are feeling your way through time in a state of grief, and I am right there with you, because we all have some level of grief in our lives.

It’s good to hear you say that. I don’t know how to read from this book. In some ways it seems obscene to read from it, because it’s deeply personal. In some ways they don’t feel like poems—more like extractions, and I really don’t want to theatricize my grief. The only way I might think about it, is that it’s not so much about my private grief, but a vehicle for connecting with other people. I don’t know if that’s successful.

I found it not at all theatrical, but raw, visceral, and surprising. The one section I had difficulty with, and I want to talk to you about, is the third section, “Littoral Zone.” I love the language in it, but I don’t know how to enter into it. I confess that I often feel this way with more experimental work, maybe because I have never studied experimental poetry, but I thought you might talk to me a bit about that and about experimental work in general and how to approach it.

Well, the first thing I’d say is that maybe those poems fail, because I don’t want them to be about needing any prior intellectual experience. Maybe they just fail, because I think especially now, after the last three years, I come back to Pound, “Only emotion endures…what thou lovest well shall not be reft from thee.” I want the poems to work emotionally.

I thought about those images made by Michael Flomen. He puts big sheets of photo-sensitive paper in streams at night, and the whole world impresses itself there—starlight and then the fish and pollywogs that slip across it and currents of water, and although the image is one dimension, it’s a reflection of several dimensions. You can’t decipher what you’re looking at or what the scale is, if it’s microscopic or something seen through a telescope.

In some sense it feels like grief does that. Grief throws all of your perspectives into confusion, of not knowing what you’re seeing and not knowing how to work with it. Each first section of the three part poems of “Littoral Zone” is a reaction to what you’re seeing in each image. Then each of the second sections has to do with perspective—a confusion about what you’re seeing, a deeper questioning of that. And then the third sections have to do with intimacy but as though the language that I had for writing or thinking or feeling had been shattered.

I think you’ve been very successful in reconstructing your language, because one of the things that I love in this book is the mix of diction. The surprise of “dab and shatter,” and the “full flag-pull” and all the unexpected turns. You have a way of saying things that goes straight to my heart, surrounded with really gorgeous, lush, not always familiar words and phrases that expand my horizon. But I think part of the problem for me with this section is that the images don’t reproduce well, so that it makes it hard to understand the relationship between the images and the poems.

We went back and forth about that, but New Directions just felt they couldn’t afford to do anything more with them.

Can you say anything more about more experimental poetry that might help people relate to less accessible work?

Experimental isn’t a very satisfying word to me. As someone said, No one has an experimental baby. Different kinds of poetry drive the art forward. I try to keep myself open to modes that aren’t comfortable to me. The ceramic artist Tracye Ware used to have a big sign in her kitchen: “Comfort Kills.” Some so-called experimental contemporary work challenges me, too. But I feel that that’s good for me. That I don’t get stuck in my ruts, am made to feel uncomfortable. When I hear work that can hop off in directions that seem quirky, I can feel as though I’m watching a mind at work that’s moving faster than my mind. So I just kind of hold on, and I can find that the effect overall is powerful and that I come away feeling that I am seeing something I haven’t seen before.

That’s how I feel sometimes about your work. That I can let go of knowing exactly what it means, and just sort of trust your mind.

So can I take a look at that section a minute? (He looks at the first poem in “Littoral Zone”). To me this seems so clear. In the first section, I am looking at the image and wonder “whether the blackness is interior.” We’re looking at the photo, and wondering what it is, is it “pelagic and vegetal” or “intestinal”? The language seems to me to be transparent, not private. And then in the second section, there are questions about the nature of perception, and then in the third section, the focus shifts to a more intimate but connected realm concerned with seeing the beloved.

And that’s the trouble with poets who think their work is clear, but seems hermetic to others. I don’t want the work to be hermetic.

I want to move now to a more difficult question, about how hard it was for you to work on this book. I could really relate to that phrase, “Everyone sees her… in his eyes,” because I think that when people know and love you, your loss is re-experienced each time to you see each other.

That is just how I felt. For a long time, I was just in hiding. And I hate talking about this because it’s all “I, I, I,” about me, while the person it’s really about isn’t here to speak. That’s the place where the real loss is.

I hate the way that everything around death has been codified, there are so many stages of grief, and it’s all prescribed. As though they’re going to take away the very particularity of your own pain and say that it’s just going to follow this scheme. All of that made me sick, so I couldn’t write, and didn’t care about writing for about a year and a half.

Then I accepted a teaching opportunity at the Squaw Valley Community of Writers with a lot of trepidation, because you have to produce new work every day. But having to produce, I found there was this gush that came up in those ten days that formed the core of this book. I don’t know—I’m glad to have articulated it because I think that not saying it, not being able to speak of it and avoiding people, I was waiting for it to become ambiguous. Because I didn’t think that I could look at it, that it was just too fierce and raw. But I’m glad that I did look and discovered a way of responding. I don’t know that it was healing. It’s hard for me to think that there is any healing from something like that.

You have a relationship that lasts most of your life, and includes all the important parts of your life. Every memory you have is connected to someone else, and every book that defines you is something that you talked about and shared with someone else, so when that person is gone, it’s like the world just retreats from you. I still feel very suspended—just sort of lightly here, and afraid really.

That makes perfect sense to me, because you’ve lost a huge part of yourself, and what’s left is all tangled up in what you’ve lost. But I really find that the way that you acknowledge your brokenness in this book, how you simply explore loss without reaching for answers, was very comforting to me. Because it’s very visceral and authentic, and there’s not much of that around. But I have one last question… what’s next?

I don’t know. I really don’t. I think of St. John of the Cross: “Entréme donde no supe/y quedéme me no sabiendo…” I entered into unknowing… and that’s what I’m doing. I’m waiting to see what my economic situation is like, and what I might do in the future. I may have an opportunity to teach now and then, I might do other things—I always have. Another possibility—I have an agent now in Barcelona, Pontas—they are interested in my novels, and I’m just working on finishing one. And an interesting director has picked up the film rights to The Trace, so that might be a movie. We’ll see.

Forrest Gander was born in the Mojave Desert and grew up, for the most part, in Virginia. A U.S. Artists Rockefeller fellow, Gander has been recipient of grants from the NEA, the Guggenheim, Howard, Witter Bynner and Whiting foundations. His 2011 collection Core Samples from the World was an NBCC and Pulitzer Prize finalist for poetry.

Meryl Natchez‘s most recent book is a bilingual volume of translations from the Russian, Poems From the Stray Dog Café. Her book of poems, Jade Suit, appeared in 2001. Her work has appeared in The American Journal of Poetry, Atlanta Review, Comstock Review, and others. She blogs at www.dactyls-and-drakes.com.