Wholly Her Figure

by Suzanne Bottelli | Contributing Writer

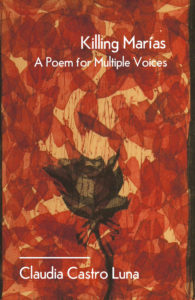

Killing Marías:

Killing Marías:

A Poem for Multiple Voices

Claudia Castro Luna

Two Sylvias Press, 2017

In an op-ed in the New York Times, Ariel Dorfman writes about how the common usage of the verb desaparecer throughout his childhood referred to a thing that had been misplaced, or to a person who had gone off somewhere without saying where. It was a word used lightly, idiomatically, when someone gently, even playfully, wondered how that object had been misplaced or where that person had gone. This word was unalterably transformed starting in the 1970s (the era of Pinochet’s dictatorship in Dorfman’s native Chile) to the point where it now refers in many languages and around the world to a crime of violence and erasure that is done by one human being to another. “They disappeared her (or him, or them),” we now say. The “disappeared ones,” we now read in the papers, or in a few history books, or in the inscriptions carved into those few memorials that now exist for the preservation of historical memory. In a similar vein, Gloria Steinem has written that phrases such as sexual harassment, female genital mutilation, and marital rape have begun finally to enter the lexicon, not because these are unprecedented practices in human history but because people are finally starting to challenge the normalization of this kind of violence as “part of life” by naming these acts as crimes, as violations of one person’s body by another. Naming such things helps to undo them, Steinem asserts.

A term created to challenge a particularly abhorrent form of violence against women head on is the word femicidio. Femicide, the murder of a female identified person because she is female—and because as such she is feared, or hated, or considered worthless in her person—has had to be invented and spoken aloud more and more in recent years in order to break the cycle of impunity and institutional silence that has prevailed regarding these killings. Particularly epidemic levels of femicidio/femicide have been unfolding since the late 1990’s in Mexico and Central America, where the bodies of women turn up daily—mutilated, violated, murdered, and discarded. Femicide extends not only throughout the Americas but also to practically every corner of the world, and is visited most often on poor and marginalized women, especially indigenous women and transgender women.

Those who speak this word femicidio/femicide have begun to name and document the murders of hundreds of women in and around Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. The women’s names (and what is known of their stories) are now being recorded, painfully and painstakingly, generally without much institutional support from either the Mexican government or the US government, whose policies are often the root causes of the violence, privation, and impunity that have made these women so particularly and fatally vulnerable. They are made less vulnerable and more powerful by this naming and by this recording of the grim cycle that binds them together.

Claudia Castro Luna’s book length “poem in multiple voices,” Killing Marías, adds an essential element to the long overdue naming of this violence by giving voice and language to the victims themselves. Undoing this cycle for Castro Luna involves not just naming these women, but also renaming them, employing a new language to revive the sanctity and agency of these women, in body and personhood. On each page, we encounter another woman from the list of victims who happened to be named María, as Castro Luna invents a diction of her own to make of each new María another face of the feminine divine, another whispered name to add to the Litany for the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Those readers familiar with the Ave María/Hail Mary may be tempted to hear echoes of that prayer (“blessed art thou among women… Pray for us… now and at the hour of our death”), but these voices are not invoked in a tone of meek supplication. Each new voice channeled by Castro Luna is that of a woman by turns raw and beautiful and defiant and human—a woman, Castro reminds us, born of yet another woman. Each of these women has been silenced by murder, we know, and yet she is calling out not to the Judeo-Christian Creator but to an aspect of the Great Mother, calling out in spiritual reverence and in a physical reclaiming of power: “Like you / we have a nested swallow cave / and a life-giving cut // All about you / is harmonious and divine.” They are calling out to us as well, seeking to shake us out of our rational, post-industrial slumber (“Beloveds! / see wholly her figure”) as we flip through our catalogues to choose what items we might buy next.

greed and ignorance

breed ordered pairs

cold economics

on a Cartesian plane

but working women

are thinking women

are feeling women

with mouths to feed

with dreams to seek

with life to love

These Marías urge us to look beyond consumerism and the false logic of production capacities and see the evidence of human suffering that hides just behind the walls of the maquílas and the walls of the detention centers, not to mention the morgues.

Castro Luna’s Marías call most of all to each other, connected in body and spirit as they join their stories together, bestowing blessings as a kind of balm as they seem to welcome each other as hermanas/“sisters” in the next world. This is hinted at early in the poem with the beautiful, childlike question: “On whose feathers / did you travel / to the world above?” But later in the poem the blessings deepen in their sense of mother love and permanence.

María, stardust

blessed your face

as it darkened

into eternal night

As far as the efforts of authorities to investigate cases of femicide, any suspected gang-related case is not generally investigated, such is the dismissal and impunity with which the gangs and the cartels—along with colluding political leaders—now operate. Worse still are the cultural and societal norms that dismiss women who may be considered to have in any way brought such violence “on themselves,” by for example walking after dark outside of their homes. In some cases investigations are foreshortened when women are deemed by the police to have been prostitutes. Such a conclusion might be drawn on the basis of appearance alone, perhaps based on what the women are wearing or whether they have red nail polish on their toes when their bodies are found. Castro Luna’s voices respond to such condescension with fury, even calling out the irony of the way these women’s murderers are often dismissed as “sons of bitches” or “sons of whores.” This common insult in Spanish and English is recast to highlight the further contempt that it places on yet more women, as “Maria Elena Throne of Wisdom” bluntly responds:

Whores birth tenderness

like the rest of us

with a slit between our legs

A particularly horrifying advertisement for designer shoes in El Salvador a few years back featured a woman spread out on a coroner’s table, her dress hiked up, her lips glossy red and her skin blue-white with the pall of death, all while wearing the shiny pair of the stilettos being advertised. The caption: “Shoes to die for.” When a woman or girl is harassed or threatened in a place like Juárez, or when she places herself into the hands of a coyote in an attempt to reach the border safely, she knows exactly what kind of grisly fate might await her, and how little the authorities or even those in the wider culture are likely to care. Killing Marías does not shy away from the physicality of such deaths, and the shocking speed with which anyone’s body left behind, whether abandoned in the desert or buried in the ground, will decay and disappear.

Maggots feast

on carrion

eventually

develop wings

bones carry on

The cycles of violence that are alluded to in this poem include not only the violence in the streets or along the border but in the home as well. In some of the most striking sections of this poem, Marías young and old share their experiences of familial abuse, including Castro Luna herself, who speaks here, remembering a childhood beating at the hands of a male relative:

I was four, maybe five

when darkness settled

wounded and shameful

in a corner of the universe

held by my ribcage

but my tongue, winged bug,

saved itself and flew

to perch atop the moon

The image of a kind of suffering both physical and psychic here is heartbreaking, yet the spirit of this child transcends the experience and bides its time, not to be silenced.

Alice Walker has written that we cannot know ourselves until we know the names of our mothers. The women whose voices inhabit this powerful collection are often the voices of mothers, whose names here are both ancestral and contemporary. They speak from a place of the imagination and a place of the body rather than from police logs or court documents. Indeed, Castro Luna’s book draws from that place of feminine consciousness and physicality in order to imbue these voices with the majesty and transcendence they deserve. The most resonant notes in this poem are those that remind us of the infinite cycle of women’s bodies giving life to us all, while simultaneously calling our attention to the limits of language. Even this beautiful poem—which reclaims the dignity, and makes visible the reality, of these otherwise statistical victims—cannot bring them back.

—

Suzanne Bottelli‘s poems have appeared in The Collagist, Scoundrel Time, Poetry Northwest, The Literary Review, and Prairie Schooner, among others. She lives in Seattle and teaches at The Northwest School.