Adam Tavel: “Let Those Sparks Arise”

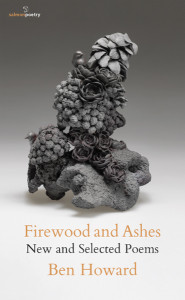

Firewood and Ashes: New and Selected Poems

Firewood and Ashes: New and Selected Poems

Ben Howard

Salmon Poetry, 2015

A career-spanning collection, Ben Howard’s Firewood and Ashes: New and Selected Poems displays the poet’s lyrical sonorousness, formal mastery, and spiritual inquisitiveness. His most recent poems occupy the book’s opening section, where aging, memory, the beauty of the natural world, and the uncertainty of human endeavor are the poet’s chief subjects. One of the most compelling among these, the titular elegiac sequence “Firewood and Ashes,” grieves for a lost friend in crisp, tersely-composed lines and conjures the final metaphor in Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73, where the dying body mirrors flame’s self-consumption. We hear echoes of the great bard’s “glowing of such fire / That on the ashes of his youth doth lie” most clearly in Howard’s fifth and final section:

Forty years of friendship.

One by one they rise,

these memories, as if

they might resume a story

or fashion out of fire

a single breathing person.

So let those sparks arise,

and let that smoke disperse,

knowing as we do

that even firewood

does and doesn’t turn

to ashes. Here and now

the flowers that you loved

are blooming near your urn

as if you might listen.

Another new poem, “Magnitude,” reflects on the flimsiness of literary reputation and self-regard, as we encounter the poet’s younger self fretting over his inclusion in an anthology, which builds to a stoic epiphany about literary—as well as romantic—ambitions: “What is maturity if not this knowledge, / However incomplete, that rest will come / Only when that lust for magnitude / Is seen for what is?” Perhaps the most masterful and polished among Howard’s latest work is the sequence “Maturity: A Work in Progress,” which impresses with its impeccable cadences and diction, but also achieves an unlikely feat: it seeks wisdom from, and atonement for, a failed marriage while also serving as an epithalamium for a son’s impending wedding. The fifth section, reminiscent of Seamus Heaney, struck this reviewer as particularly compelling for its imaginative leaps and emotional charge:

Is it not a con, that bogus notion

that all of us are victims of each other?

Today the victim’s Jane, tomorrow John.

And all the while we’re making heavy weather

of each new slight, each real or misconstrued,

exploitable affront within our fiefdoms.

So let me skim away that yellowed curd

and sip the milk of truth, if not wisdom.

And let me now recall the well-known yarn

of the boatman in his still unblemished boat

who struck another of a foggy morning.

Irate, irrational, he threw a fit,

only to find the other boat was empty

and therefore void of consciousness or story.

I dwelt in ignorance, as people do,

and so did she. What more is there to say?

A few new poems underwhelm, such as “Early Retirement” and “My First Taste of Sherry,” as they find Howard sentimental; for this reader at least, both poems stall out at wistfulness. “While Waiting for the Doctor,” another unfulfilling poem, engages us a vivid, anxiety-ridden scene of a patient’s thumb-twirling—replete with tongue depressors and cotton swabs—but fails to develop, and ultimately deflates with an uncharacteristically flat final line: “though anything can happen any time.” Thankfully, such instances are rare, as poem after poem, Howard’s gifts for observation, introspection, and eloquence capture moments of insight without excising the messiness of life.

For readers new to Howard’s work, the poems culled from his six previous collections present a bounty. “The Boar,” one of Howard’s oldest inclusions from 1979’s Father of Waters, recounts a gory, ritualistic slaughter that transforms into an allegorical rejection of violence. “Because You Asked for a Bedtime Story” from 1990’s Lenten Anniversaries confronts doom with the gloomy majesty of E.A. Robinson. Among Howard’s finest is “Holy Water” from 2004’s Dark Pool. A tourist narrative, it begins simply enough with the happenstance passing of a holy water fountain in an Irish churchyard, but blossoms into a courageous affirmation of negative capability. What Randall Jarrell once wrote with understated reverence for Frost’s “Directive” is worth invoking here: “one stops for a long time.” In lines 5-8, for example, the speaker complicates the hallowed scene with human motives, where the churchyard stones “Took on the slanted light of early evening / And voices softened, not in reverence / So much as confidence or privacy.” Line 15 disrupts the sacred air even more, as the fountain’s sign is described as being “insidious,” so six lines later, we sense cheekiness when the foundation itself is described as “that latent spirit cloistered in a pipe, / Its fluent cadence silenced by a valve / Though primed to be released at any moment.” By the poem’s conclusion, the speaker rejects the superstitious rite of taking a drink while simultaneously upholding the mystery and might of the metaphysical:

What was it stopped me? Say it was a sense

Of something tangible behind my shoulder,

By which I mean no priest or risen ghost,

Much less a stern protector of the State,

But something I’d brought with me to Tralee,

A figment of a once and future longing.

Would that it might sustain me or be gone.

Would that I might pass and leave no trace.

Howard’s restless spiritual searching, free from judgment and informed by Zen practice, unifies Firewood and Ashes. His poems are notable and noble in their craft, heart, and panoramic gaze. For a half-century now, he has written poems with one foot in the Romantic tradition and the other firmly planted in our modern predicament. His verse participates in the eternal search for truth and beauty amid our contemporary struggles, yet resists vernacular speech, excessive ironizing, and pop-culture allusions as devices to hold our attention. One hopes this representative gathering of poems old and recent will allow a new generation of readers to discover Ben Howard’s lush wisdom—a wisdom rooted in the poetic tradition and attuned to our fraught young century.

—

Adam Tavel won the Permafrost Book Prize for Plash & Levitation (University of Alaska Press, 2015). His recent reviews appear in The Georgia Review, Rain Taxi, The Chattahoochee Review, and CutBank Online, among others. You can find him online at http://adamtavel.com/.