In Discussion // “The Collected Poems of Chika Sagawa”

On September 13th, the APRIL book club gathered at Little Oddfellows in the Elliott Bay Book Company to discuss The Collected Poems of Chika Sagawa (Canarium, 2015). The book gathers poems published during Sagawa’s lifetime (1911-1935), presented in a chronological fashion, while also including Sagawa’s prose and unpublished work.

Participants in this discussion included Seattle writers Quenton Baker, Frances Chiem, Sarah Baker, Willie Fitzgerald, Bill Carty, and Jane Wong. Wong, who chose the book and led the discussion, previously wrote about Sagawa’s poetry for the APRIL blog, and describes here how she became interested in Sawako Nakayasu’s translations:

I’ve been following Nakayasu’s work for years, and was excited to delve into her translations. Sagawa’s poems were new to me! They struck me as both vibrant and vulnerable. I was immediately drawn to Sagawa’s ability to shift from image to image and place to place, without warning.

For example, in “Visibility Through Green,” she writes: “Run! My heart / To her side as a sphere / And then in a teacup.” We’re always left with the question: where are we? Yet, because of the speaker’s assured voice, we don’t actually need an answer. We trust her.

Because insects appear so commonly in Sagawa’s work, Wong began the discussion with the question of what insect each person would be. The group—alternatively consisting of a spider, a water strider, a dung beetle, and a small colony of bees—then spent roughly an hour informally discussing Sagawa’s densely layered images and metaphors. That conversation is presented here in a condensed form. (BC)

Jane: One thing that really struck me was a sense of Sagawa’s death throughout. I found something ghostly and eerie in the poems. What did you all think?

Frances: I actively avoid biographical details as much as possible until I’m done. So I actually didn’t read about Sagawa’s death [of stomach cancer at age 24] until after reading the poems, and I didn’t have that same ominous sense. But at the same time, her poems are heavy with natural imagery, and within nature, the presence of death is constant.

Jane: I agree. We approach nature thinking of life, but she definitely focuses on the element of death. Of course this is a “Collected Poems” so there’s not necessarily an order, but “Insects,” the first poem, is a great example of this:

Insects multiplied with the speed of an electric current.

Lapped up the boils on the earth’s crust.

Turning over its exquisite costume, the urban night slept like a woman.

Now I hang my shell out to dry.

My scaly skin is cold like metal.

No one knows this secret half-covering my face.

The night makes the bruised woman, freely twirling her stolen expression, ecstatic.

Bill: There’s precision in her description, and it often only ever accumulates into mystery. That line—“Half covering my face”—a lot of the poems contain a similar secret. Things accrue, but not necessarily toward a specific scene or occurrence.

Sarah: In the center of the poem, the first person is isolated to the point where we don’t identify the “I” as either the bug or the woman. It becomes both at once.

Jane: She has stepped out of her body, then she steps back in. That happens a lot in the poem. You get that sense of the speaker seeing herself from the exterior and then going back in. Like an insect literally sheds its whole body.

Willie: The introduction of the “bruised woman” throws everything preceding it into this terrifying light. A lot of the poems are about night—night coming on, night falling—and there’s this “terror twilight.” I agree that a lot of the poems are unnerving. This line especially: “My scaly skin is cold like metal.”

The first line is about movement, as is the last line. The second stanza is about this costume, and the second-to-last one is about this covering. And the insect is in the middle. The center is the insect persona, with shells surrounding it. There’s a formal layering.

Jane: Also, biographically—thinking of Sagawa as one of the first Japanese modernists—Japanese poetry before then was so focused on the revelation, and the thought that there is this larger world to be revealed, and let’s distill it into clean meaning. She does the opposite.

Frances: In a lot of contemporary poetry, there’s much more of an effort to keep nature and the human-built world separate. I liked the appearance of the woman here. It doesn’t seem separate from the natural world. She doesn’t make any allusion to humanity being elevated above the insect.

Jane: All of these elements—human, insect, gender, the unnatural world—are on equal grounds.

Frances: The narrative I imposed on the poem was that she was freed by the night because she didn’t have to explain herself. There wasn’t the oppression of being seen with the bruise. She acknowledges a lack of hierarchy in the natural world, and is freed by the night because she can be outside without the falsely imposed hierarchy of the human.

Sarah: And the night hides the bruise.

Jane: Night plays an important role throughout. It’s not our hour. It’s when insects come out and are attracted to light bulbs, when raccoons are free. Even in the terror of being bruised, she has freedom. It’s a weird, ecstatic celebration.

Quenton: The distinction of urban night is interesting too. There’s a qualifier at first, but later in the poem “night” stands alone, which appears to make one night “truer” than the other.

Jane: The city night has different dangers. She’s turning the traditional fields of cherry blossoms into the city and leveling the playing ground between the unnatural and natural world. And she was young when she wrote this!

Quenton: Can we talk about “Backside”?

Jane: Why this one?

Quenton: I try to keep in mind when reading this—a posthumous collection—that these aren’t the order that Sagawa chose, but I also can’t help but be affected by the order. When I read “Night eats color” and think how much color and night are in the book. It’s like a head-to-head match. It’s like the playoffs. These are two dominant themes.

Bill: Her lines—like “Freely twirling her stolen expression”— start in one direction and end somewhere else. I felt the same way with “Day falls into the leaves like sparkling fish.” The metaphors always elude tidy comparison or linear logic.

Willie: Her verbs work really hard too. On the opposite page, in “One Other Thing,” asparagus “dives into the dirty afternoon sun”. You immediately understand the vertical motion. The same thing happens with “night eats color”. It’s really active.

Quenton: There’s an economy to that.

Sarah: She keeps it moving too. The sparkling fish also “writhe” like the “lowly mud.”

Jane: The twisting motion can be gross to look at, but beautiful at the same time.

Bill: Like insects!

Jane: Even the word “tickle.” Would you ever be brave enough to use the word “tickle” in a poem? No! I would never do that. But there’s something about the tone of her voice that is authoritative, and certainty to the way the lines are constructed. The last line, “And the people move forward”, doesn’t make any logical sense, but I believe that it’s true.

Willie: In Nakayasu’s introduction that line is interpreted as hopeful. But for me, it was almost scary.

Sarah: It’s almost as if Sagawa is thinking, “Despite of all of this…the people move forward.”

Jane: We have no choice but to move forward.

Quenton: The condition of poetry is one of hope, naturally. I don’t think that there exists such a thing as a non-hopeful poem. You have to believe on some level. And belief becomes a matter of fact.

Sarah: The people, because they are acting, feel like the most tangible thing here. Everything else disappears as she brings them up.

Quenton: She’s an illusionist. She uses sleight-of-hand, and then moves to the next image. The repetition in the poem—“And writhes…”, “And the space…”, “And the people…”—links the changes in state. And the people move forward. You shift into what you have to become.

Frances: “Promenade” was a poem that really stuck with me:

Seasons change their gloves

The three o’clock

Trace of sun

Of flower petals that bury the pavement

A black and white screen

Eyes are covered by clouds

Evening sets on some promiseless day.

Here there are more urban or human-created images. The gloves, the three o’clock trace, the pavement, the screen. That idea of the “promiseless day” is interesting. I took it to be in conversation with the expectation that the poem would be about nature, or the threat of things outside of human control, versus the reality of the total neutrality of all things.

Bill: This recalls “Backside” for me. I think we can read some hope in the “promiseless day.” If the day promises one thing or another, it sets up expectations. If it’s promiseless, it’s an opportunity, a vacuum for things to rush into.

Jane: And “some” adds a matter-of-factness that exists in many of Sagawa’s poems, while in others, there is intensity. Take “Green flames.” Its ending is the opposite of matter-of-factness:

…people are crazy here there is no point in feeling

sorrow nor in speaking their eyes are dyed green believing

grows uncertain and looking enrages me

Who blindfolds me from behind? Shove me into sleep.

She’s full of the opposite of apathy. She’s angry. There’s a constant shift toward these interior moments where she is clearly a person who feels things.

Quenton: I wonder about her age too. How would she have written in her thirties, forties, fifties? With many poets we get to follow an arc, but we don’t have her arc.

Frances: In a lot of these poems we’ve discussed, there’s a recurring theme of time too. I wonder if she was already feeling her quickly ending life.

Quenton: You can see that in the prose too. She’s definitely aware of her difficult state.

Bill: In “1.2.3.4.5.”, which is the last of the published poems included in the collection, there’s another example of states changing:

Under a row of trees a young girl raises her green hand.

Surprised by her plant-like skin, she looks, and eventually removes her silk gloves.

She begins with with metaphorical language…

Jane: …but what actually happens is that she’s removing her gloves, but she sees the action before it occurs.

Quenton: This is a great ending poem.

Willie: Nakayasu mentions in the introduction that there is a lot of Portuguese, French, and Chinese in the book that we don’t see in the translation.

Bill: And some English.

Jane: Yeah, that’s too bad. That would be one criticism of the book is that it’s not a side-by-side translation.

Quenton: That has to be a rule!

Jane: That’s why I would suggest “Mouth Eats Color” as well as this book. Nakayasu gives that collection the subtitle of “Anti-translations.” She includes full poems in translation, but some are not translated. Some are in Chinese, some Japanese, some French. It’s very transnational.

We get stuck in a very American context, and we might assume that in Japan, they would be reading in Japanese and only speak Japanese. But Sagawa was schooled in so many different ways.

Formally she’s very interesting too. She’s breaking out of Japanese forms. She’s playing around with genre. A lot of the lines are very long. I like that fact too. I appreciate her formal negligence. It’s wild.

Quenton: She’s very transgressive.

Jane: Which isn’t easy, particular in her time.

Bill: The introduction also mentions her essay, “Had They Been the Eyes of Fish.” She writes, “I believe that the work of a painter is very similar to that of a poet. I know this because looking at paintings wears me out.” That sentiment seems O’Hara-esque.

She goes on: “When painting a single apple, I do not think we should attribute the concept of roundness or redness to the object.” I think this relates to a lot of how she uses metaphor. We have to do more than identity something as red and round. How do we get at this accurately, showing the way an apple may be rotten, the blue, or swollen, as she says. She resists perfection in her image, in her logic.

Jane: Writing a poem isn’t just the explicit “aboutness.” It’s about the essence, or core values. I think children do this very well. They are able to describe something without the basic words we use to represent something. And I think that is why Sagawa’s poems seem mysterious. There is no aboutness.

She gets at what’s emotive and ephemeral. It makes the poems less distanced, and I feel we’re welcomed in a way. Not “we’re all in this together,” but more like “come here.”

Willie: It beckons you.

Jane: And you might not have a choice.

//

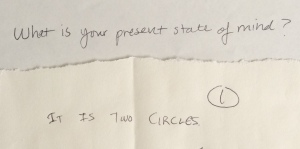

Because Sagawa had such an affinity for Surrealist art and writing, a game of Associative Q and A—the results of which are posted below—ended the discussion.

//

Quenton Baker is a poet and teacher from Seattle. His current focus is the lived, racialized experience in American society. He is a 2015-16 Made at Hugo House fellow and a 2014 Pushcart Prize nominee.

Sarah Baker recently received her MFA from the University of Washington, Bothell. She has worked with Wave Books and is a co-founder and co-editor at Letter [r] Press, a collectively-run publisher of handmade books, ephemera, and the Small Po[r]tions journal.

Frances Chiem (née Dinger) is a writer of fiction and essays. Her work has appeared in Fanzine, Poets & Writers online, Washington Trails and Kill Screen Daily, among other places. She works in environmental advocacy and is also marketing director of the APRIL Festival, an annual event celebrating independent literature held in Seattle during the last week of March. She tweets @f_e_chiem.

Willie Fitzgerald is a co-founder of APRIL, a festival of small press publishing. His short stories have appeared on Everyday Genius, Hobart, Pacifica Literary Review, City Arts and elsewhere.

Jane Wong is the author of Overpour (Action Books, 2016) and teaches at the University of Washington and the Hugo House.

Bill Carty is an Associate Editor at Poetry Northwest. His poems have recently appeared (or will soon) in the Boston Review, the Iowa Review, Pleiades, and Oversound. He teaches at the Hugo House.