Interview // “Gazing Into the Self”: A Conversation with Saba Keramati

Saba Keramati’s debut collection of poetry Self-Mythology (University of Arkansas Press, 2024) shatters the mirror and looks at the fragmented self through a myriad of lenses. The poems in this book are astute conjurings of the self, some real, some imagined. These poemsdraw on different forms mirroring the poet’s many identities, singing what it means to inhabit stipulated spaces and how to make that space one’s own. Keramati meditates on the serendipitous quality of our being, the beauty in the specificity of one’s heritage but also the multiplicities we carry in ourselves.

I was very grateful to be able to have a conversation about serendipity, lineage, both in life and in poetry and the process of writing this collection via Zoom.

*

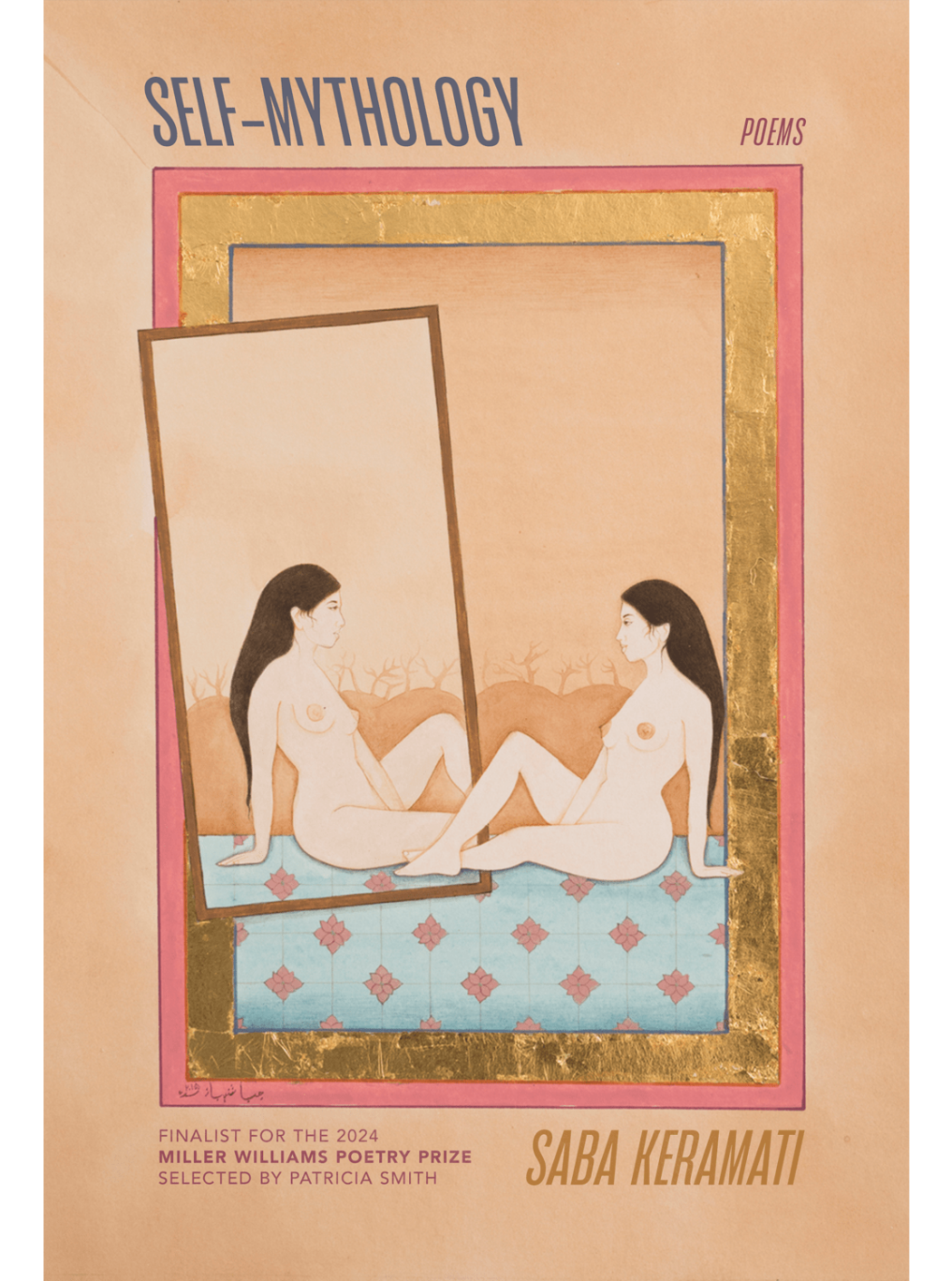

Aditi Bhattacharjee (AB): I just wanted to start by saying how I came upon your book. Usually I pick up books, not because I read a great blurb or someone gave a great review, but more often than not I pick up a lot of my books because I gravitate towards them. It’s this unexplainable pull that draws me towards it and that happened with your book. It’s a stunning book, it’s a stunning cover. Congratulations!

Saba Keramati (SK): Thank you so much! That’s like the sweetest thing that I’ve ever heard and I am so glad that it found you and now we can chat and we got this opportunity to meet in person.

AB: How are you feeling?

SK: Yeah, good! I was much more nervous before it came out and since then I feel like I’ve learned that the people who have found it or the people that I’ve met through it have been so kind and so generous that I’m just like okay if it never wins an award if it never…you know? I don’t care about that, I’m just so grateful for the opportunities that it’s already given me. And the chance to truly meet so many great people. All my writing stuff, even before the book, like going to workshops, I’ve always just been like oh my god everyone I meet is so amazing. I have met so many wonderful friends through all this and I care about them reading it. People that I’ve met through the book too, I feel like we’re just all kind of meant to find each other and that’s really been the best part of it.

AB: Yeah, community for the win.

SK: Absolutely. The publishing side of it, you know, it’s really rough, so I feel that if you get community out of it you’re moving in the right direction.

AB: Going off of that, I wonder if there were such writers or works of writers that you have stumbled upon, maybe not recommended to you per se but had that gravitational pull toward, that you now know and that have been imperative to your writing life?

SK: That’s a great question. The answer that comes to me first is Leila Chatti. I am obsessed with her work. It’s actually kind of a wild story how I discovered her. She kind of was recommended but not really. When I was in grad school, a classmate of mine was attending AWP and she came back and she was like I bought this book for you and it was Leila Chatti’s chapbook. And she said I saw this woman read at AWP and thought you’d like this book and bought it for you. In that way she was recommended to me but it was more like somebody who knew me and vibed with what Leila was doing and wanted us to know each other in that way. I read that chapbook, Tunsiya Amrikiya, and went on a deep dive on the internet and tried to read every poem she had ever published.

I was so eagerly waiting for Deluge and when Deluge came out (it is very different from Tunsiya Amrikiya) I was like this is THE book. And that book was very pivotal for a lot of my learning as I was putting my first book together.

I am trying to think of another book that I was drawn to. Oh you know, Jane Wong, How Not to be Afraid of Everything?

With that title, I am so going to read that. And that was my first discovery of her even though she had books before that but I hadn’t read any of her work and it was just that book, that cover, that made me go I must read this and she is brilliant in every way.

AB: How does one become a poet? Or know they want to be a poet? It sounds silly but I am interested in understanding the journey, say, was there like a canon event that happened in your life that led you to that realization of wanting to become a poet.

SK: I’ll start by saying that I was always really interested in writing. Even as a kid I was writing silly poems and stories for myself but I never took the poetry aspect of it super seriously. I thought I was going to be a fiction writer for so long because my father has a theatre degree and he’s very into theatre and movies and he kinda raised me on these narratives. I was so sure that I was going to be a fiction writer. And when I was in undergrad, you had to take the Introduction to Fiction writing course and to be able to take it any further. And in that class, I was forced to write poetry. They told us we had to write fiction and poetry. I think we did the fiction unit first and I was vibing, but then we did the poetry unit and I was like oh wait! I like this so much better.

I liked it better and I also thought that I was better at it and so my teacher of that class was like you really should take the next level up and I really liked that class and the teacher as well. The intro class is where we do a workshop (and it is really an intro) and there are a lot of people who are just taking the class to just take it, but the next level up were people who were interested in it and people who really wanted to stick with it. So that was my first experience with a real poetry workshop and it was so good. It was just like okay now I am sticking with this and I never really want to go back to fiction.

AB: In “The Dream” the speaker says “Have a small heart. There is too much to lose otherwise / Yearning is dangerous.” And then the poem “What’s Lost” starts with the lines “I have always shrouded myself in poems / I thought I was clever but I was hiding.” On one hand there is this loss that the speaker is pointing towards in terms of identity, language, heritage, and on the other hand there are the six self-portraits through which the reader is offered a glimpse of the multiplicity of identities that are being created and recreated. So, I was wondering about the decision to call these “self-portraits” and having all of them in the book. It feels like an active choice and that only a book like this (dealing with selfhood) could have had.

Was there ever a moment where you debated putting all of these poems in this collection or did you consider calling them something else because there are so many other poems too in the collection that read like self-portraits, you know, for example “Inside the Museum, a Remnant” when the speaker identifies with “A simple bowl: blue and white” and says “For the first time, I feel less impossible”?

SK: Wow thank you so much for reading it so closely! I am so honored and I love that question. No one’s asked me that yet. I think, well, when I was in grad school, my teachers were like you need to expand. They were like you can’t keep writing about yourself in this very pointed way. And that’s totally the advice that I needed because I needed to be able to risk and try different things and through that advice I did end up eventually writing about myself again, but it allowed me to expand what was happening within the poem even though the whole subject itself might have turned it back toward the self. I think there, in the self-portraits, there is an active choice, and a stillness of the speaker that’s like okay these are moments I am purposefully thinking about myself. Then there are poems where this is what I am noticing from the outside and it’s making me reflect. It’s more a choice to be like I am gonna take this moment to really focus in on my body and focus in on what I am feeling versus an outside factor making me do that. Because when I think of a self-portrait, specifically in art on canvas, there is so much choice in starting that, and thinking what you’re gonna paint yourself in that moment so I kinda think of it in that way. What is the speaker’s gaze on, in that moment.

AB: Was there a poem that you were personally close to that you wanted to put in the book that is not in there right now and what was it like making that choice?

SK: There was one poem actually, that I took out at the very last minute. And it was a poem about having a meal with my dad in California. So, it was mostly about the dad and California and the fires. And as I was going through the book I was like, the dad is such a secondary character especially to the mother because a lot of the book is a focus on the cycle of matrilineal heritage. And it was just like, oh my god I love this poem and the poem was actually published in a lit magazine and it was in the book till the very very last minute. The reason I really didn’t want to take it out is because I love my dad so much and not because this is the poem that really needs to be here.

Once I was able to separate that and be like okay it doesn’t make sense to have one poem that’s really just focused on this because it adds more questions than it gives answers, I ended up replacing it with another poem that I had written about fires and that kind of did the same work. Because the fires and California appear a few times so I kind of liked the back thread in the book, but the thread of the father wasn’t long enough to weave through all the way and I didn’t want to have just one poem that didn’t make sense in the narrative. Maybe I will find another place for it one day but yes, I didn’t want to introduce this sort of another character without giving them the opportunity to be fleshed out.

AB: The first poem of the collection “There is No Way to Say This” grapples with immigration and the violence of living in America, yet realizing that the speaker wouldn’t exist if not for the dream of America. It’s quite fraught, that piece, and reads like a declaration as well as an apology. Can you speak a little to the impulse behind starting with this poem versus say ending with it? Because, I mean it’s such a…it’s a poem that I feel like it could have been the centrepiece, the collection could have ended with it, so what was the impulse behind choosing to begin with that poem.

SK: I mean you kinda nailed it. I thought about ending with it. I had thought about having it smack dab in the middle. I played with it a lot. It’s really funny because technically it is the opening poem but I almost don’t even think of it that way. I keep calling it the prologue in my mind and I think of “Hollowed” as the first poem. And when I was in grad school “Hollowed” was the first poem I had in my thesis that I turned in. When I was writing “There is No Other Way to Say This,” it was really about needing to fit as much as I can in one poem that gives as much context as possible to who I am, but also to who the speaker is right now because there’s a lot about memory. The poems that are happening as a child are not meant to be in the present; it’s all in the past. It’s very much a looking back and understanding that perspective. So, I wanted to give the reader the same understanding of what it is right now so that they can enter the narrative part with that knowledge. And I also needed the reader to know right off the bat that I am multiracial, the child of two immigrants from two different countries. I needed that information in the book in one poem and I ended up starting with that poem. I really think of it as a prologue and there is technically like a section break after that poem.

AB: It does feel like connective tissue in a big way, and race and lineage are such major themes in the book, which brings me to my next question. In the poem “The Act” the speaker is seen contending with their mixed race and then further on in the collection, in the poem “Self Portrait as Two” the speaker is contemplating the dilution of that racial lineage. There is a constant tension throughout this narrative right? I mean it matters so much to the speaker but there’s also that realization that eventually, further down that is going to get diluted. I am curious, to know, what were some takeaways for you as a writer because this is such an inward-looking collection too.

SK: Well, I will say that as I think about it more today, you know contending with lineage, I’m like I really have to get over the fact that people don’t have children just to have another version of themselves. Right? And so, if I can get past that point then it becomes less of an issue, and in terms of like, you know my mom’s Chinese and I don’t know Chinese at all and I don’t even think she ever even had that question until she probably married my dad, of like what am I going to do if my child looks Chinese. It wasn’t a problem for her because I think she didn’t have that thought until it happened. So, maybe I just need to forget about that as an obstacle, you know, when it comes to whiteness. That’s obviously more fraught because of the society that we live in. But, I think the takeaway as a writer have been like hey look, there are all these x, y, z things that you do to connect with your culture and your past and it becomes so much less about what you look like and more about the acts, the rituals that you are taking. So I think working through that in the book was very helpful in working through that in real life.

AB: Yes, yes I get that. So much of the book is so intentional. The voice is so intentional, the images too. One of the things that I really liked about the book was all the mouth imagery. The way that the mouth is used metaphorically. How it stands in for language, voice, speaking or not speaking, asking or not asking, saying or not saying, and how all of these mean different things. It’s done so well and it’s so rich.

SK: I am so honored that you actually noticed that. Thank you.

AB: There are three centos in the collection in addition to an ode, a nocturne, an ars poetica, a ghazal, and so many other forms. I sensed a want for community in the poems, but also not completely feeling part of that community (maybe for not knowing this heritage intimately enough), but I wanted to ask about where does this form come into play in this whole design? Or, I mean the choice to have so many forms in the book?

SK: For sure, on one hand I just love writing in form. I think it’s such a good practice in constraint and you get to experiment so much within this little box that it is almost freeing in a way because I know I only have 14 lines or something, so how much can I fit into these 14 lines, how strange or funky or what different things can I do. So as a writer it feels very fulfilling.

In the book, I think I definitely wrote toward form as I was putting it together. The centos were what kicked it off actually. I was in grad school and I was legit having writer’s block. I didn’t know what I was going to write about and I had all these books strewn across my dining table and just flipping through them and finding lines and collaging them was so much fun and yet it also made me notice that all the centos were still in first person. I noticed that a lot of people in my heritage, in my lineage are doing this thing that I am doing, so how can I bring them in? How can I expand that also by putting them together? And then I got to point out people and be like see I am not the only ‘I’ which is something I was a little self-conscious about.

I think in a lot of contemporary poetry books these days you see at least like one or two poems that are written in a different voice and this one is very much in the same voice. So I was like okay, at least I have the centos to kind of expand that, bring it into the real world more maybe for people who don’t experience these things that I am experiencing. So when I was doing that, I was like how can I pull at the American canon too or the lineage of poetry, and that’s when my ghazal and the abecedarian came in. I think that, in that vein, there are a few references to Walt Whitman and I love Walt Whitman. I think he is loved poet but I also want to expand this form and lineage of American poetry that I have been raised in and learned through and make it bigger than it began.

AB: Is there a poetic theory or advice that someone gave you that has helped you as a writer?

SK: The one that I remember most vividly is in 2018, I was at the Kenyon Review Writer’s Workshop and my workshop leader was Solmaz Sharif. She is brilliant in every single way and everything that comes out of her mouth is just absolute genius. She told our class to “write like you know you are going to die” and I was like I don’t even know what that means but something about it gave me a lot of permission to risk things. Because when I thought more about it…like when I was trying to get my book published…I got a lot of rejections and they’d be like oh you know like Vincent Van Gogh didn’t get discovered until like after he died. And I was like I don’t care, I don’t care what Vincent went through. I want the experience of living through it now and that’s part of the community aspect that we were talking about right at the beginning that the book brings me opportunities and these are the things that I want out of my life and the book is a vehicle that allows me to have that. And so, when I think of writing like you know you’re gonna die I think, yeah! Write the heck out of it. Write whatever you want to write right now—

AB: Urgently.

SK: Yeah, and just do the thing that you need to do and don’t worry about what happens after. So, something about that provided a sense of freedom. People do ask me a lot, like how do you write about your parents? Don’t you worry about what they think? That’s like (shrugs) maybe, maybe but I can’t control that and it would be so much harder to write if I worried about that constantly. Or like, when my book was for pre-order, my high school swim coach was like, Oh my god I just preordered a copy! And I was like I hadn’t thought about this man in like 20 years and there’s poems about my vagina in my book, he’s gonna read that? What!?

AB: Well, we are so glad that you wrote despite everything and as if it were the last day. This was truly lovely! Getting to talk about your book but also about the writing process. Thank you so much for your time and for being so candid and open.