I Unthread and He Arranges Me

Dujie Tahat | Critic at Large

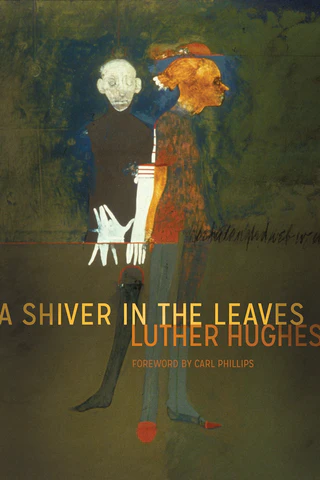

A Shiver in the Leaves

by Luther Hughes

BOA Editions, 2022

If you were familiar with Seattle before the last decade—before the effects of global climate collapse so forcefully imposed themselves onto our little corner of the world, where unprecedented wildfires raging across the western slope of the Cascades now give us smoke season in October when, before, a different kind of gray, overcast and cold, used to settle in—then you know that the cliché “it’s always raining in Seattle” is overblown. What people who’d never been to The Town unknowingly meant when they asked after rain was mist. You should know, dear reader, if you don’t already: Seattle mist hit different. It met you as you walked through it, always warmer than you expected. With shape and heft, never as formless as fog, the mist, as I knew it in my childhood, was a comfort. As an adult, I can only recall a handful of recent Seattle mists—each occurrence now a surprise. I walk out the door. The mist greets my face. Immediately, I’m looking around for someone who’s been here long enough to know the feeling—to share in this familiar embrace, even as it now portends catastrophe and its attendant griefs.

If you know, by simply looking, whether it’s haze or mist obscuring your view of Tahoma as you drive south on Rainier Avenue, A Shiver In the Leaves by Luther Hughes is for you. This book is just that mist—familiar, shared, warm, and wet. It is a book about Seattle—the people, the landscape, the changes in the city, the changes in its weather, the longing of its settler-colonial progressive promise, and the bodies that try to make a life here. It is a book about how the city—obsessed as it is with non-straight-white-male identity as a proxy for a liberal politics—makes a spectacle of young, Black, gay men. The passive performance of adoration, after all, is always easier than active accountability and redress.

ASITL is a book about loss and grief, sure, but it is, perhaps more importantly, a book about coming to terms with joy and, if not always joy, contentment with the life one finds oneself living and, if not that contentment, then a cessation, at least for now, of a prior longing for that same life to end. It is a book that is so artfully filled with ideas, but in short: it is a book about making the bed and falling in love. It is a book about mothers and tenderness. And it is utterly, relentlessly, pornographic. In this way, ASITL is, too, a book about vision: what is visible to whom, and how visibility is not, in and of itself, material power. It wrestles with these contradictions while knowing that power hides in plain sight and visibility is neither entirely powerful nor powerless. Hughes’ awareness of how power structures and is structured by vision is perhaps most striking when looking is framed as a directive:

Look left, past the cop with lawngreen eyes, crow’s feet,

past the elementary school, past the halfway house

I was told was once beautiful and foolish with children,

past the viaduct, and on the main road next to the Chevron

(can you smell the gas), a girl an eyelash short of eighteen

is being held up by a cop for her taillight, leaving a party sober,

asked to “Get out the car,” and then as she reaches to unbuckle—

“The Death of a Moth”

In this poem, the speaker pulls our attention past the police officer and their own knowledge of the city’s particular geography towards another parallel interaction that, perhaps, ends in death. None of us are free from violence—potential and real—enacted by the state. A Seattle police officer recently killed Jaahnavi Kandula only to later joke that her life “had limited value.” That we know this through body-cam footage—a technology of accountability that lets us “see” what the officer “sees”—shouldn’t be lost on us. There is no illusion. However, here, in this poem’s moment, the speaker is in total control. The audacity of the compounded, left- and right-branching syntax that builds and unifies this world requires a vision greater than sight.

Hughes’ speakers are intently attuned to attuning, and Hughes’ poetic vision is a heightened, calibrated articulation of the violence imposed by white corporate interests and their elected sycophants on the city that raised us. From the details of the first cop’s face to the gas station to the imagined end of this young woman, Hughes traces out a constellation of figures that make myth of their own being. Hughes repeatedly returns our attention to this mythologizing form of power through people and the spectacle they become. Whether they are directing our attention to the electricity between two lovers or the charge between a police officer and the person staring down his gun, Hughes points us toward the different positions our bodies can occupy and the echoes of power between them.

Looking, we are reminded again and again, is, too, about being looked at, about where, in the act of looking, agency and power begin and how that changes depending on who is doing the looking. Hughes looks at subjects looking at one another looking upon a shared space. In their attention to how the subjects of their poems offer attention, Hughes sees through public performance and captures a distinctly Seattle aggressive passivity, one built on a liberalism of identity politics wherein recognition of an other (without having to contend with, much less cede, one’s own power) is the height of moral good. Hughes exposes looking as a kind of wanting, as an enactment of some kind of desire, and the attendant mutability of that desire when the self is removed from the equation. Hughes uses looking as a form of documentary—an accounting of the oppressive, racist machinery that displaces the people they love from the city they love even while their highly visible identity is lauded.

What do we owe to one another? Hughes speakers always seem to be asking. At what point in the looking (or watching) does my perception of an-other become a duty to that person? I’m asking myself that question. A recent viral clip of Fox News coming to town is as good a reminder as any that there is no ethics in making a point about watching people suffer. As I read ASITL, I was constantly reminded of a likely apocryphal observation masquerading as craft advice for fiction writers:

All stories boil down to two narratives:

1) a stranger comes to town, or

2) a hero goes on an adventure—These are the same stories depending on who does the telling.

Now, instead of narrative, think spectacle. Who is watching and who is being watched? In the age of hypervisibility and hyperreality, we are all familiar with the feeling of being watched. Depending on your social positionality and circumstances, that sensation can be accompanied by great excitement or heart-stopping fear. These aren’t mutually exclusive.

Sex is a spectacle. Hughes’ work is pornographic. Pornography as the explicit, often visual, expression of a consummated desire. Porn closes the gap between the subject and the object. It supplants want. Muzzles eros. Kills desire. Pornography doesn’t stimulate the erotic, it merely enacts its aesthetic. If abstraction is the first form of violence, Hughes knows—and this book keeps telling us—that aesthetic representation is neither reprieve nor an assured form of safety.

The speakers in ASITL are searching, always aware of their surroundings: “I know I look for answers everywhere” (“When Struck By Night”). They are aware of their own limitations in a world full of limitations: “The truth is, who knows what will happen to either of us” (“Stay Safe”). Watching oneself is the first step towards appraisal, the first step of wanting. “So much is my want / for everything black around me to live.” Where desire springs, there is always a lack, and for Hughes, this experience comes with an awareness of their speaker’s own narcissism. “I can’t help but study / things that bare my resemblance / and that makes me a narcissist, ” noted power bottom Hughes writes about their speaker’s obsession with black birds (“The Dead Are Beautiful Tonight”). In a poem of 18 sentences, “He wants another hallelujah in bed with me and I don’t blame him” is the only sentence wherein the lover is the subject. The gag: the sentence is about how good in bed the speaker is.

I unthread and he arranges me

on the bed how he sees fit, ready to love me

the blackest way he knows how—salt

in my mouth, light in the corner of my eyes.

This passage is ostensibly about sex positions—but for Hughes (and I’d suggest all of us) the desire from which sex positions arise is tied to a kind of lineage. The subject-verb base of the sentence, “I unthread,” evokes a line tracing out strands of succession. However, the sentence is compounded, and the speaker is met forcefully with another who does the arranging. This is the complicated nature of lineage—lineage in this city, Blackness, queerness, the beating heart that pushes one’s life ever forward. No matter how well one looks or watches or searches, someone else (or more likely, many others) orders the terms within which the searching is done. The sentence goes on, enacting the unthreading, branching right, constantly being modified—until we end with two discreet subordinate clauses, noun fragments that cannot stand alone as complete sentences, fragmented parts of the speaker’s body we can only aggregate through the lover’s arrangement. Lineage always ends with the body, perhaps even lines of bodies that know, intimately, the salt of the ocean, their own tears, another’s sweat, or some nameless lover’s cum. And here Hughes pulls off a master stroke: the insistence of “my” mouth and “my” eyes in Hughes work brings me to my own. While there are a great many lineages Hughes and I do not share, I know waking to light in the corner or my eye, how near-tears trap light as I choke, when the glint of my own glistening cheeks might obscure my own perception of what’s happening before me.

**

Before we go further, I should note: this review is not “objective” (whatever that might have meant in the parlance of its time). This reviewer loves Luther Hughes dearly. I have been inordinately lucky to think and read alongside Hughes for years; I’ve even had the great fortune to encounter some of these poems and this manuscript in draft forms. Whether our shared thinking led us to similar interests or vice versa, luck and fortune are inadequate superlatives for how deeply Hughes’ poetics of place, longing, and desire are embedded in my own. Among the many things Luther and I do share: we both love Seattle, this imperfect city we call our home, this absurd bastion of passive-aggressive liberalism that pushed Black and brown people past the city limits to make way for the corporate office buildings, luxury apartments where art houses used to be, and the light rail.

So much of ASITL takes place in and around public transit. My favorite poem in ASITL takes place riding the Light Rail. In it, Hughes—like the promise of the Sound Transit project, itself a decade from completion—weaves together desire and lineage in the context of a gentrifying city:

There was no train then. No man reading.

There was me and her. My father

had gone off and married his true love.It’s childish of me, but I believe

in true love, in the way It can lumber

the lumbar. How it twangsthe tongue into twinflower.

Too, the yowl of hate.

Look at me. I’ve fallen to haze“In The City I Become, Become”

The attention to every poetic unit in this section alone—line, sentence, stanza, sound, diction—heralds Hughes as one of the great poetic minds of our era. But let’s begin with how the first tercet is an adroit feat of narrative and stanza. The opening line both sets the scene and positions a passive observer of the scene—simultaneously, pushing against (if not all the way breaking) the fourth wall by looking at us readers of ASITL. The second line gives us characters: speaker, mother, father. And the third stakes out conflict. The three stanzas in total have four, two, and four sentences respectively—creating a syntactic compression and expansion across the more or less similar-sized unit stanzas. This mirrors the speaker’s attention from narrative to imaginative speculation on love to the puncturing of a daydream that often comes with self-reflection.

“In The City I Become, Become” deserves its own dissertation, but let me turn your attention, momentarily, to the last line of the second stanza: “the lumbar. How it twangs // the tongue into twinflower. / Too, the yowl of hate.” Here Hughes melds the lower spine and the mouth with reverb. Through a dazzling array of sounds, the words are transformed beyond their denotative meaning into their own unique experience. The fragments become some other whole. They become.

“Too, the yowl of hate.” is both a sentence and a line even as it lacks a grammatical subject and serves as a short coda to the previous exhale. There is no doubt about the certainty of that sentence-line because, at the point of its summoning, the language, as much as anything else, is the subject. Mirror becomes light. “Look at me” the speaker says, driving out any ambiguity that the poem isn’t aware of its own artifice. But whereas artifice might imply cheap replication, this poem’s artifice not only makes meaning but creates experience. It is distinctly its own. A spectacle made by its own imagining.

I, too, love people-watching on public transit. Robust, reliable public transit is a city’s throughline. When I visit a new place, one of my favorite things to do is to take a train or bus from one end of the city to the other just to watch how the types of buildings, people, and labor change from neighborhood to neighborhood. Before the Sound Transit Light Rail system took off in Seattle, there was the unreliable (Martin Luther) King County Metro and if you wanted to get from Mount Baker to the University District, you listened to the Blue Scholars:

Take six quarters out of the pocket. Drop it in the box.

Hop the 48, off to pay homage. It stops often.

I jot my observations, watching citizens walking

off of the Joe Metropolitan.

“Joe Metropolitan” (Bayani, 2010)

If you, too, follow the great literary tradition of people-watching on public transit in King County, you’ll have noticed first you need more than six quarters (ride fare has nearly doubled since then). You’ll have noticed, too, the explosion of population over the last decade: Seattle, Kent, and Bellevue were all among the the 30 fastest growing cities in America in the previous decade. On either the 48 or the light rail, the commuters have become more homogenous as the historically segregated south end, which not that long ago boasted some of the most racially diverse zip codes in the country, has become whiter thanks to gentrification. If you clock the various high-tech company badges hanging from belt loops and lanyards, you might have observed, too, that Software Developer is now the metro area’s most held job—beating out long-standing retail sales. Unsurprisingly, the median household income has nearly tripled since 2010 from $33k to $97k—despite white households in Seattle making three times the amount as non-white households. Still, the most transit-dependent communities remain chronically underserved. Whole swaths of the South Sound don’t have timely access to emergency care in situations where every minute matters. While it normally takes 18 minutes by car for a student to get to South Seattle College from Rainier Beach, it takes over an hour and fifteen minutes and multiple transfers on public transit. And while one in five seniors don’t drive, many who live in senior centers don’t have adequate access to bus routes.

No art is made in a vacuum. So ASITL is, too, about the changing nature of a city. From lumber to aerospace, Seattle has always been a company town. The crown currently belongs to Amazon. I could go on about the union-busting and its illegal and unethical employment practices, but in The Town, where most of its employees are white-collar workers, the company’s greatest sin is a near-total lack of interest in place.

I came to know South Lake Union, Amazon’s current headquarters, as the home of Re-Bar, the divey, lesbian bar that every Tuesday night served as the home of the Seattle Poetry Slam. Right before quarantine, I met a couple—both employed by Amazon—who had lived in SLU for nearly three years and had never heard of Columbia City or Beacon Hill or Rainier Beach (all historically, predominantly immigrant, Black neighborhoods). By their own admission, the farthest they’d ever ventured in our shared home was one bridge north across the ship canal to Ballard (a historically Nordic, white, blue-collared enclave).

To care about a place, you have to care about the people who live and work there. By nearly every metric across every tier of the company, Amazon demonstrably does not care about place. They made a campaign out of a search for a second “home” wherever they carved the biggest tax loopholes for them. The company has created a culture that lacks care for the people around them. The company’s litany of abuse—especially with respect to its warehouse workers—is long and well-documented, but even setting that aside, two out of three new hires in 2021 left the company within 90 days, and former workers were twice as likely to leave by choice over being fired. They have an alarmingly high churn rate for white-collar and executive roles, a function of morally bankrupt values that structure a dehumanizing performance evaluation process that prioritizes efficiency and output over the people doing the work.

Attending to the people doing work means attending also to the people those workers have displaced. No impact evaluation is complete without contending with the often invisible displacement that comes with growth. In Seattle, the history of invisible displacement in the service of “progress” is as old as its first white settlers: the Collinses, Maples, and Van Asselts. The Duwamish people are still fighting for federal recognition. And in today’s south end, white people continue to encroach on land that, over the last century, Black, brown, and immigrant people and families have called home. Despite Seattle’s reputation as a very white city, Hughes, raised in Skyway, knows The Town primarily through Black spaces. As gentrification marches on, those spaces shrink and, if luck will have it, working-class non-whites move elsewhere in South King County.

Hughes’ speakers throughout are constantly walking the knife’s edge of spectator and spectacle. This Mobius strip of spectacle-spectator is the constantly looping surface on which ASITL turns. It is a magic trick of evasion and vulnerability—exposure by way of a constructed feat. In that vulnerability, Hughes stakes out power. The poems are charged with electricity. When we’re talking about desire, we’re talking about power.

We’re talking about desire even—maybe especially—when the speaker’s vision is turned on themself. Like a hallway of mirrors or like driving by the East Precinct or like walking through the empty storefront for lease on the first floor of new high-rise apartments, ASITL constantly reminds me of my own body—its desires in the context of a changing city, how what it wants shifts as the rooms around it change, when it thinks instead of feels. When Hughes does this, it is not mere evocation. It is a return to the body, an invocation to slow down and revel in it. I am grateful to Hughes, their body, and their body of work, which teach me so much of how to be in this city and in relationship with those I love.