An Empire Elsewhere

Troy Osaki | Critic at Large

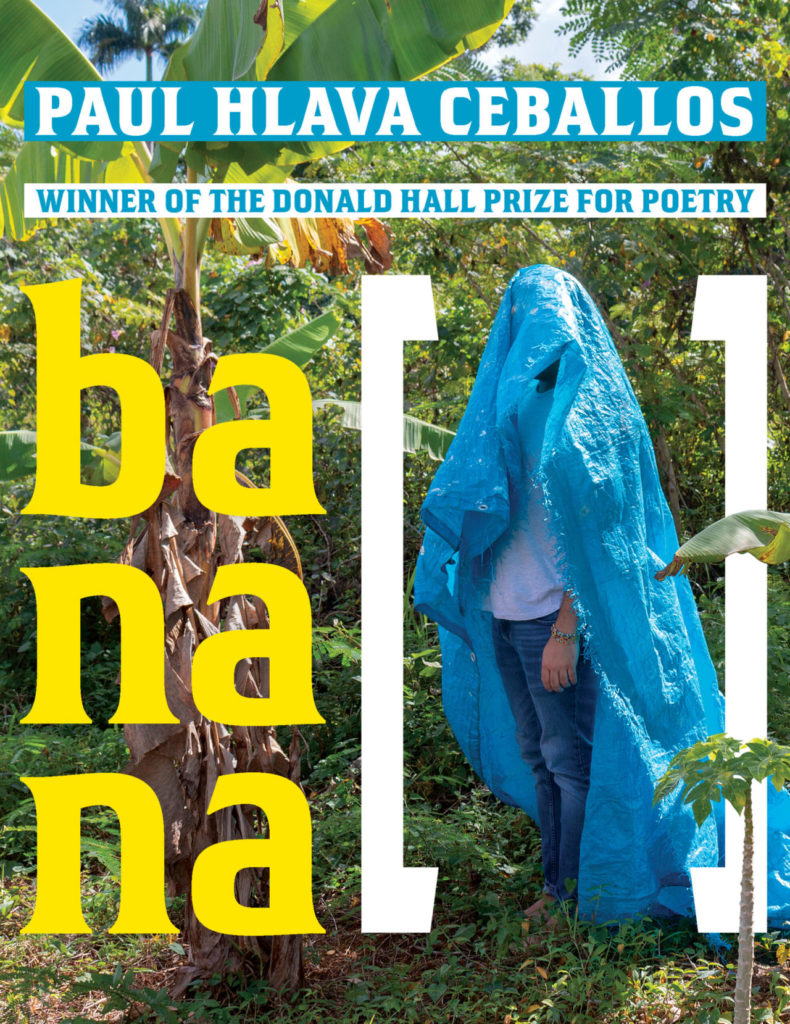

banana [ ]

by Paul Hlava Ceballos

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022

At the end of last year’s Seattle summer, I attended my first anti-trafficking conference. I remember, most, a migrant worker who stood at the front of the room and told us, “All Filipino people belong to the Philippine nation––our job is to stop forced migration.” We spoke about the struggle of overseas Filipino workers: caregivers, childcare providers, fast food service workers––people from our home country who, in seeking better economic opportunities outside the Philippines, were taken advantage of. Agencies advertising fake jobs. Employers locking away passports, stealing monthly wages.

For me, this was a new way to understand human trafficking–as not only an individual experience that people fall into, but also as a structural effect of a country that’s semicolonial and semifeudal, a nation whose sovereignty continues to be violated by U.S. imperialism so that foreign corporations can extract cheap labor and raw materials. The Philippines is rich in natural resources like rice, coconut, lumber, oil, seafood, and minerals, but our people remain extremely poor. A country that should be self-sustaining, the Philippines is instead export-oriented and import-dependent. We’re an archipelago that imports frozen fish, a nation of peasants and farmers who can’t afford the rice they grow. These conditions have led to upwards of 6,000 Filipinos leaving the Philippines every day in search of work overseas. In total, more than 10% of our population lives outside the country. Our people are forced outwards in search of finding better economic opportunities elsewhere.

Paul Hlava Ceballos’ debut poetry collection, banana [ ], is concerned with a similar extractive relationship that the U.S. has established with the Americas, one in which people are forced to flee their home countries in search of opportunity and safety in the imperial core. He shares his community’s complex and haunting experience of U.S. imperialism in Central America, including that of his own family. Through the use of elegies, historical texts, and memories, Ceballos documents the crisis of capitalism, how it’s continued to worsen over time, and its brutal impacts on agricultural workers, farmers, and working class people.

In the opening poem “Genesis,” the speaker poses the question:

Did Adam first teach God the word semilla

or resource extraction?

From the beginning, we’re asked to consider the kind of relationship to land we’ll be examining throughout the book: Will it be that of semilla–seed–with which comes growth and a country in bloom for those who belong to it, or will it be one of extraction, where natural resources are taken and shipped away to benefit an empire elsewhere. Ceballos’ use of couplets in this poem illustrates what might become of the land, its two possibilities. Each represented in a line of its own but held together as a unit as if placed in necessary struggle against each other.

We then see how abundant the land is throughout the collection such as in the ending long poem named after Ceballos’ mother, “Irma,” a moment in which the speaker reflects on land, family lines, and the eventual distance between both. The speaker shares:

My 4th-grade textbook featured

a quarter-page photo of grasslands and llama

but in my AP World History book

our country did not exist.

I open a family album and out spills schools of tuna.

Ceibo cotton flames on the next page

with tío’s paychecks after dollarization.

The speaker names resources found in what’s presumably their home country, some of which are found in abundance. Not just several tuna fish but whole schools of them. In these descriptions, the speaker places their family next to these natural resources, side-by-side, showing the close, inseparable connection between them and the land, a relationship tied together, often, as seen here, through labor power.

Then, in the same poem, the speaker points to the extractive relationship between U.S.-owned corporations and the land:

…of rainforests razed for Texaco oil,

We learn of these relationships from the speaker through memory and distance––opening a 4th-grade textbook, a family album. The land is rich in natural resources and can presumably sustain life yet the speaker themself isn’t in the country but rather outside of it. Similarly, we’re introduced to the speaker’s family who is also elsewhere and left years before, no longer living on the land they come from. The speaker shares their mother’s experience:

She does not remember

that country, she insists

shipped here when she had only 14 years.

She crossed the long desert

From a seat at 40,000 feet.

The recurrent use of memory adds another dimension to the collection’s understanding of distance in all its forms. Not only is the speaker separated from their home country by physical miles, but also by time––removed by several generations. In this way, the extractive relationship between the U.S. and the land isn’t limited to what’s taken physically as resource and raw material but also includes the years, which often turn to generations, stolen from those who are forced to migrate, unable to live on the land to which they belong.

Ceballos captures the violent reality oppressed and exploited people face due to U.S. involvement in their home country’s economy and politics that force them to eventually leave. Through elegies, we’re made aware of the horrors they face after fleeing to the U.S.

Ceballos crafts an “Elegy for Roxsana Herńandez”:

Between the terror of that place

and colder terrors of this one…

Roxsana Herńandez, a Honduran transgender woman, joined a migrant caravan in 2018 seeking asylum in the U.S. She was placed in what’s become known as las hieleras, or ice boxes, frigid, cramped holding cells in Customs and Border Protection facilities. Having spent 16 days in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody, Herńandez’s autopsy report revealed deep bruising and injuries consistent with physical abuse while handcuffed. She died of dehydration and complications related to HIV. The use of elegy here, and throughout the collection, allows readers to mourn individuals like Herńandez while at the same time creating a space to grieve what may be dying with them––sovereignty, freedom, democratic rights.

The poem finds Herńandez in her “long march north,” traveling between terrors. However, one thing remains the same in each place––an American presence. In lifting up Herńandez’s story, Ceballos is at the same time lifting up the history of Honduras, a country that has endured over a century of economic exploitation by U.S. corporations such as the United Fruit Company.

Honduras’ economy, like that of the Philippines and other Central American countries, has historically been oriented toward exporting its natural resources, including one such resource significant to this collection: the banana. This restructuring of the economy to serve the export of bananas was so significant to the development of U.S. imperialism that in 1904, American author O. Henry coined the term “banana republic” to describe Honduras and its private commercial enterprises, profiting ruling class, and as a result, its extremely unequal and stratified social class structures made up largely of impoverished working class people. It’s under these conditions of intense exploitation of the working class by oligarchs in collaboration with foreign corporations that the violent conditions examined by Ceballos’ collection emerge. In Herńandez’s case, we learn:

“Trans people in my neighborhood

are killed and chopped into pieces,

then dumped inside potato bags––”

In reflecting on Herńandez, her story, and everyone else we haven’t heard of, Ceballos captures what I’m thinking about in a quote by Carlos Arguedas, a banana farmer and union organizer, who says:

For us this was both illogical and unjust as there were so many homeless

workers, so many unemployed banana workers who were suffering.

For us the most sensible thing was to make use of this land by planting

what we eat.

By using historical texts and direct quotes, Ceballos’ intention is to deliver the truth, to say what needs to be said at its bone––that land, sovereignty, and an end to exploitation are important to stopping the forced migration of people in Central America and the world over.

In Banana [ ]: A History of the Americas, we see this, again, put simply:

I’m going to tell you about some of my experiences working in the banana sector

200 of us crammed into shacks eating boiled bananas

out of empty kerosene cans

the most gorgeous of all food-giving plants

the banana, is everywhere

Through Arguedas’ quote and the plain facts we learn that what’s simple and most practical is what’s kept furthest away from the toiling masses in the interests of the ruling class. All of this echoes back to the beginning poem, “Genesis.” A reminder, for me, of why my people migrate across oceans and why millions of people from the Philippines to the Americas are forced to leave their homes every day.

Each body has its own small gravity.

The banana pulled the world when it fell.

The grandson of Filipino immigrants and the great-grandson of Japanese immigrants, Troy Osaki is a poet, organizer, and attorney. Osaki is a three-time grand slam poetry champion and has earned fellowships from Kundiman, Hugo House, and Jack Straw Cultural Center. He was awarded a Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry fellowship from the Poetry Foundation in 2022. A 2022-2023 Critic-at-Large for Poetry Northwest, his poetry has appeared in the Margins, Muzzle Magazine, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, and elsewhere. He holds a Juris Doctor degree from the Seattle University School of Law where he interned at Creative Justice, an arts-based alternative to incarceration for youth in King County. He lives in Seattle, WA.

Paul Hlava Ceballos is the author of banana [ ], winner of the AWP Donald Hall Prize for Poetry, the Poetry Society of America’s Norma Farber First Book Award, and a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. His collaborative chapbook, Banana [ ] / we pilot the blood, shares pages with Quenton Baker, Christina Sharpe, and Torkwase Dyson. He has fellowships from CantoMundo, Artist Trust, and the Poets House. He currently lives in Seattle, where he practices echocardiography.