Interview // “Openings out of the Overlooked”: A Conversation Between Jenny Xie & Paul Hlava Ceballos

by Paul Hlava Ceballos | Contributing Writer

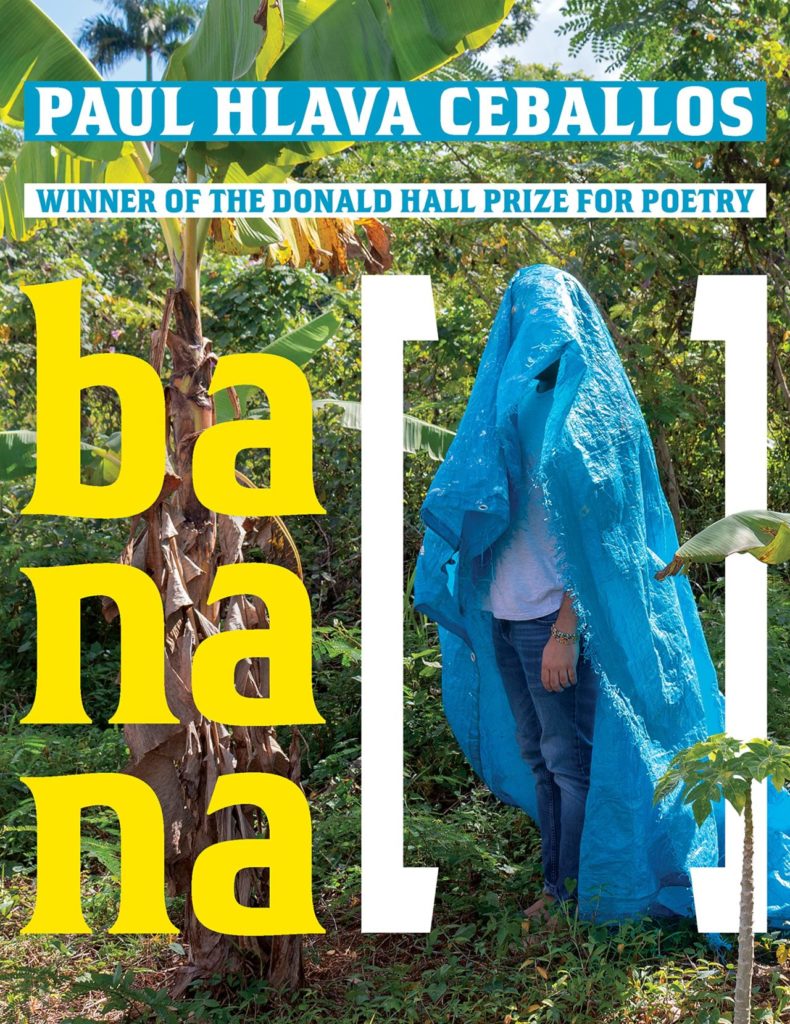

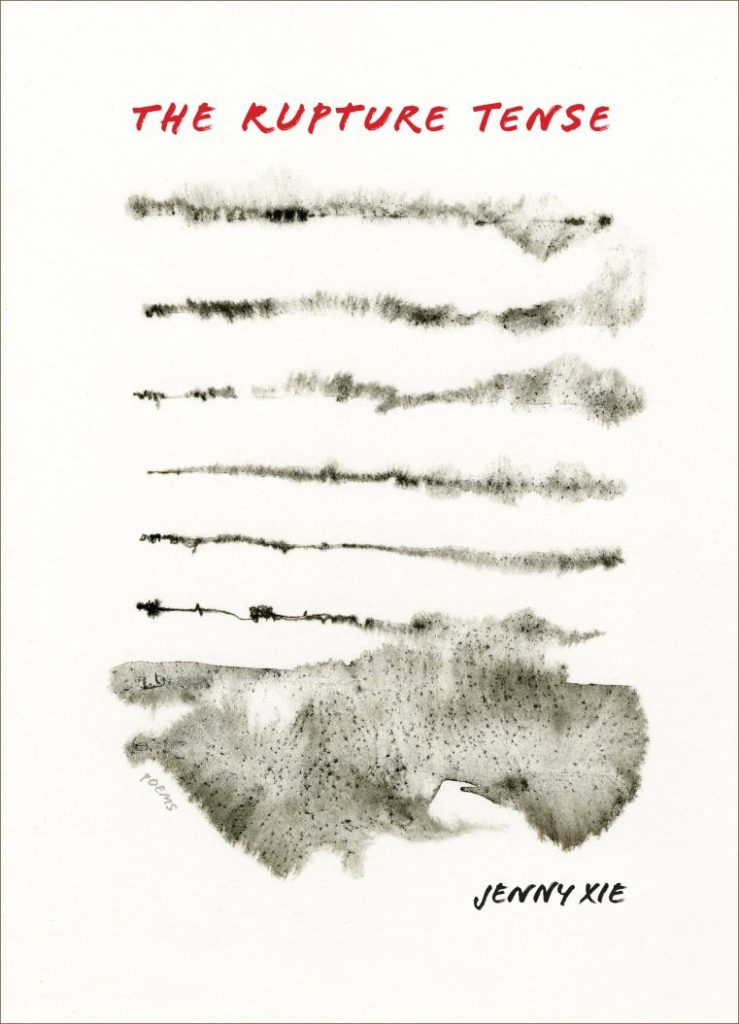

In 2014 in New York, I joined Writing-Across-Cultures, a workshop through Cave Canem led by Eduardo Corral. While that workshop was instrumental in how I now understand poetry, meeting Jenny Xie was a highlight. I was moved by the depth of her poems and the acceptance I felt in conversation. How exciting, then, that nearly a decade later, both of our books should be released in the same month. Of her second book, The Rupture Tense, Rigoberto González writes, “Her stunning language enacts a journey through an emotional landscape where we listen to the pain of the dead and the grief of those who inherited the terrible stories . . . Disquieting and gorgeous.” My debut full-length book, banana [ ], which won the Donald Hall Prize for Poetry, will also be released this September. Jenny and I had a discussion about hacking away at archives, counter-historical texts, re-entering the past through lacunae, and the spaces opened up in writing about family.

Jenny Xie (JX): One of the most striking dimensions of banana [ ] is how it interweaves many voices, awakening us to polyphony in archive, and allowing for currents of conversation between those at the margins of empire, ancestral ghost presences, and voices dragged to the surface from long-buried state and historical documents.

Reading the collection, one feels the weight of archive, which you handle so deftly and with such surprise. The sheer amount of documentation must have been daunting to approach, I imagine. I’m thinking in particular of the middle section, which is comprised entirely of found source language from declassified CIA documents and other commercial and historical texts. What were the unexpected challenges of this labor of reading, of excision, and of this process of archival investigation you embarked on for much of banana [ ]? Can you explain the compositional logic behind your process of sifting, redacting, and erasing? What was guiding you throughout this process?

Paul Hlava Ceballos (PHC): Thanks for the question! First, I want to say that The Rupture Tense is stunning and will likely be a text I return to in perpetuity. Both of us are working to unearth an archive; your work has me thinking about what lies below the text—Li Zhensheng’s photos and the history that the photos document, and what lies above the text—the silences of what currently remains unknown or known but unsaid.

With banana [ ], it was the unsaid that guided me into the source texts. There is a violent history that brings us bananas, as well as most of the products that fill our homes, but it is a history that tends to be casually ignored in our daily interactions with these products. So how do I speak in a way that acknowledges these histories?

I spent the first three years of the poem not writing but reading. I started with the Chiquita Papers and C.I.A. archives, and then I just started following books’ footnotes into other books, copying any sentence with the word “banana” that mentioned money, paramilitary violence, or just had pretty gardening language. By then, I had about 150 pages of typed notes.

Curating the first line was terrifying. My apartment floor was covered with notes, with small walking paths branching between pages. It was paralyzing to see all the possible permutations of language—miles of sentences folded into that space! I was also aware of the limit of my research—any line I put into the poem took away from a line I could use in the future.

I’ve been thinking about content recently. Content, unlike form, isn’t something we edit in a traditional poetry workshop. We remedy the container but not the substance it encloses. Working within the archive, it matters that the majority of the content available to us is state-sponsored, white-supremacist, militarized. In my research, I found lots of Chiquita Banana commercials, lots of corporate press releases. To answer your question, what guided me was a desire to use my lines sparingly to damage the content that we, as consumers, are given.

Well, I think I have more to say beyond damage and toward repair. But here I’m thinking how The Rupture Tense grapples with the power of the eye. The action the viewer does to a photograph of a bloody revolution “to reinscribe it with motion and the creases of time.” Did you ever want to damage the content of the archive? Alternatively, were there any delicate steps you had to take to avoid doing harm?

JX: It’s remarkable to consider the three years you spent immersed in acts of research and excavation, and to envision the material mass of all of the language you were gathering. I can understand how it would be “terrifying” to decide on the first act of shaping, of plucking out one branch of language from all of those dense thickets. The paralysis of figuring out the right approach. And then where to go from there after that first act, and what to augment and or give voice to in subsequent acts of arranging.

I want to linger on your phrase “to damage the content we are given,” which points to the creative, and ethical, forces inside the process of decreation. Banana [ ] renders visible, and indelible, the campaigns of terror and bloodshed enacted on Ecuadorian farm laborers and union organizers by the U.S. empire, and it illuminates this violence through hacking away at, and violating, institutional and commercial archives, and by refusing to reproduce the imperial narratives in them. To frame what you’re doing across some of these poems as desecrating is illuminating—it mirrors in its verbs what was inflicted on the workers, communities, and land, but in the service of recuperating those lost voices. I think about how in certain sections, you expose the rot and virulence behind the ubiquitous presence of the deceptively cheery banana; it’s stunning to hear the language of pestilence—as applied toward banana crops—echoed in bodily mutilation.

In relation to your approach, I was also interested in how to animate the archive, and draw out the unsaid and the silenced. In The Rupture Tense, I don’t know that I was consciously aiming to “damage” the archives I chose to confront—which were largely unearthed photographic archives from the Chinese Cultural Revolution and family oral archives—so much as create more openings in them. When writing about Li Zhensheng’s smuggled-out photographs of the Cultural Revolution, I was similarly paralzyed by how to begin writing, of how to reframe and re-see an artifact that was already so rich, and shocking, in its visual language.

Ultimately, I thought that my intervention in those photographs—if one can call it that—would be to invert the background and foreground, to create openings out of the overlooked. What are ways of looking deeply, at a photograph or other archival filament, that allow us in the present to re-enter the past? To see the future in them? What can I do in my work to add movement to something from the past seen as inert? In that way, I suppose any authorial intervention is in some ways a violent or aggressive gesture, a way of imposing one’s presence.

I’d love for us to move into the use of images in your book, specifically the photographic images you employ. The images of farm workers and banana plants are intriguingly cut up, severed, even. Some images look purposefully dismembered. Across from one poem, movingly depicting the exhaustion of labor, we glimpse a part of a photograph that’s but shaved to resemble a small dark leaf or feather. Then, elsewhere, in the last section of the book, we have striking familial portraits, I assume of your mother. Can you speak to how you were approaching the photographic form in this collection?

PHC: I love that thought! What are ways of looking deeply that allow us to re-enter the past? I wonder if a careful look can be a small window we bore into the suppression of history. It brings to mind how Chiquita has released press statements acknowledging the terrors of their predecessor, the United Fruit Company, without completely changing how current workers are treated, or acknowledging how their economic influence in Latin America currently affects migration to the U.S. By insisting the past is a completed action, exploitation of the people who survive can continue, guilt-free. So, by peering backward, can I see ahead?

Movement that draws the reader through The Rupture Tense is deftly enacted by the speaker’s vision. By making the background of Li Zhensheng’s photos the foreground, a distance is collapsed within the implied depth of the photo, but also between the speaker and the background of the photo. This movement inward is modeled for the reader, so when the speaker moves from the photo into the actual landscape of the photo (the country, though displaced by time) the reader is also pulled into that aperture. Multiple visual framings are collapsed to a single point: image becomes actual, distance is near. Through this relationship, the uncle seeing the accused Rightists in paper dunce caps is experienced by the speaker, and the reader. Sight is not passive. I am inside the poem, among relatives, eating an overripe melon.

The photos in my book are also an attempt to see who has been left out-of-focus, in the margins. They are people from the background of photos of banana plantations. In the first picture of the title poem, I used gardening shears to cut out the billionaire banana-magnate from the center of the frame. That revealed the worker hidden behind him, a thin crescent of a shoulder and back with a cowboy hat.

As you mentioned, much of the poem works to mirror what was inflicted on workers back on the language of the company, and state. As I did this, I wondered how much I inherited empire’s violent strategies as one who lives, and makes art, within it. In an attempt to move beyond damage to repair, I brought the images and voices of workers into the text. Even so, the pictures of workers are severed because they were never the foreground; only fragments survived their picture-taking and the editorial process of their record keeping.

Well, I should say that the first three years of that poem was just research; the second three years was simultaneous research and writing. I don’t think I began the photos until the 6th year. But creating the white space around the workers’ pictures made me want to be more silent in the future, and to write into my own silence, though I don’t know exactly how that will look. The final poem has pictures of my mother and family, along with her very regionally-specific idioms because that is what I have and love, and I wanted to end on images that were whole.

The Rupture Tense is also structured around family. Though we may see people only in passing, their voices are so rich. The cousins, aunts and uncles, and grandparents we glimpse feel complete. What was your experience writing about them?

JX: That’s a beautiful claim: that sight and vision can act as mechanisms of movement, of distance travel and of shuttling through time. In the poems that comprise the first section of The Rupture Tense, I’m trying to puncture the membranes of the past, the future, and the present, and allow them to leak into one another, through acts of looking and re-animation. I was holding in mind the writings of certain theorists of photography—Walter Benjamin, Ariella Azoulay—who claim that photographs hold in them “spark[s] of contingency”: elements that sneak into the photograph, that cannot be silenced, that go against the will of the photographer and even of the subjects of the photograph. And how in these elements, there’s the possibility of destabilizing how the photograph will be viewed by a spectator in the future. Azoulay, in her The Civil Contract of Photography, argues, “The photograph is out there, an object in the world, and anyone, always (at least in principle), can pull at one of its threads and trace it in such a way as to reopen the image and renegotiate what it shows, possibly even completely overturning what was seen in it before.”

A spectator, in pulling at the threads and overturning how a photograph was once seen, allows the past and future to make contact. That thought gives me chills. To circle back to your comment, it’s an act that refuses to let the past be a sealed thing, a “completed action.” Your process of cutting up archival photographs with gardening shears is a terrific demonstration of how to “reopen” the past, and magnify the overlooked, which is also where the subversive nestles.

Outside of the photographic image, I think we’re both taking similar actions of re-animation with regards to familial archive and memory. In my case, I wanted to “re-watch” memory—especially memories transmitted to me by family members, family lore—and give certain calcified memories movement again. I was also trying to create something that would speak honestly about my complicated feelings around going back to my birthplace for the first time after thirty years, and being unsure of how to navigate complex family dynamics and untold histories.

I struggled quite a bit about how to approach writing about an experience that eluded language and narrative. One point of difficulty was how to achieve a kind of emotional honesty about my subjective experience while still protecting my family members’ freedom to be unknowable. It mattered to me that I didn’t wound anyone with how I wrote about them—though I suppose there’s only so much one can really control in that regard. Along the same vein, it was also essential for the poems to show that the speaker, a loose stand-in for myself, was an outsider, one set of eyes among many. The narrating presence of some of the poems is someone who is trying to read the past and the present, and those around her, but does so impartially and imperfectly.

I’m curious about the last section of banana [ ], titled “Irma,” and if you faced similar reservations and quandaries when writing about family and familial archive. There’s such tenderness in how you infuse familial memories with myth, and how you draw up new origin stories out of overlooked details and episodes. I was really taken by the wonderfully textured memories threaded throughout, such as a mother learning how to use a dishwasher, or a brother confusing snow with breadcrumbs. At the same time, there are moments where the mother figure contests a memory, or is somewhat tight-lipped about the past (e.g. about living in Kansas, racist incidents, or crying during her citizenship test). I was moved that you included these moments, and how they give agency to the mother, who might want certain parts of the past to remain closed or opaque.

PHC: Yeah, I also struggled, especially in the final poem, with how to approach a subject so close to me—my mother and our relationship through her language. That poem begins with a lie she told me—that my memory of going with her to her citizenship test never happened. For years I believed her, that this pivotal moment in how I understood her place—our place—in our country was something I imagined or dreamed. I believed that until I found some of her documents online. So I wanted to talk out why she concealed that for the decades she lived here before I was born, there were times her sponsorship or paperwork lapsed, years that she went back before returning to the U.S., and that her time here was not always secure. The poem wonders what it means to belong, and who decides who belongs. So while acceptance is at the heart of it, the poem’s questioning is in conflict with her reticence.

I’ve been thinking about Susan Sontag’s essays on photography a lot during our chat: “To photograph is to frame, and to frame is to exclude.” It feels important to say that my mother is someone who traditionally is excluded from the frame. Hers is not the hero’s journey. It’s more than that—the daily struggle to provide for a family as a not-white immigrant mother in America. When writing about the photographic practice of exhibiting colonized peoples, Sontag wrote, “The other, even when not an enemy, is regarded only as someone to be seen, not someone (like us) who also sees.” As you pointed out, my mother’s reticence or pushing back against my memories is necessary to show her as someone who sees, who exists inside and outside the framework of the text.

In the years that I took recording her idioms and asking about her history as I wrote that poem, she became more and more willing to share. So seeing and writing did affect our relationship, and subsequently, how I see and write.

I’m interested in those complicated feelings around going back to your birthplace. I wasn’t born in Ecuador, but so much of my family’s culture and mythology is tied to that place. When I went as an adult, I was overwhelmed, to say the least. I think going there changed how I understand myself in relation to the many countries and people that I’m connected to. How did you feel? Did writing—and finishing—The Rupture Tense affect how you felt?

JX: I’m moved hearing about how you cede control of the poem—so to speak—to your mother and her voice. How many dimensions of her you invite onto each page, and how you let her flicker outside of your framing. And of course, how her voice is the last one in the collection—finally reaching for a word that escapes her.

In a similar spirit, perhaps, I wanted the poems that touched on my return to my birthplace to go off the tracks of conventional narratives of diasporic return—ones of that foreground either a flooded sense of belonging and kinship, or a sense of remove and alienation. My experience was full of contrasts and incompatibilities: of being in the position of the outsider, the kin, the intruder, the documentarian, the returning loved one, the naive cousin/niece, the American, the severed, and so on. My relatives felt both like intimate family and strangers, and I became a stranger to myself, learning the contours of selves through their projections and gazes.

In the writing of The Rupture Tense, I wanted to preserve all of those complicated cross-currents of feeling and fidelity, and honor what doesn’t bind to the usual neat narrative threads. I wanted to leave air in the margins, in the silences. I see this in your long sequences, too, especially the closing one of the collection. There’s tenderness in fragmentation, and honesty in how disjunction allows in ambivalence and interruption. We’re allowed, through fragmentation, to feel the distances between seeing and being seen.

–

Jenny Xie is the author of The Rupture Tense(Graywolf Press, 2022), recently longlisted for the National Book Award. Her first book, Eye Level (Graywolf Press, 2018), was a finalist for the National Book Award and the PEN Open Book Award, and the recipient of the Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets and the Holmes National Poetry Prize from Princeton University. Her chapbook, Nowhere to Arrive (Northwestern University Press, 2017), received the Drinking Gourd Prize. She has been supported by fellowships and grants from Civitella Ranieri Foundation, Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, Kundiman, and New York Foundation for the Arts. In 2020, she was awarded the Vilcek Prize in Creative Promise. She has taught at Princeton and NYU, and is currently on faculty at Bard College.

Paul Hlava Ceballos is the author of banana [ ] (available here), winner of the 2021 AWP Donald Hall Prize for Poetry, chosen by Ilya Kaminsky (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022). His collaborative chapbook, Banana [ ] / we pilot the blood (3rd Thing Press, 2021), shares pages with Quenton Baker and Christina Sharpe. He has received fellowships from CantoMundo, Artist Trust, and the Poets House. His work has been published in Poetry, Pleiades, Triquarterly, BOMB, Narrative Magazine, among other journals and newspapers, has been translated to the Ukrainian, and nominated for the Pushcart. He currently lives in Seattle, where he practices echocardiography.