Where the Sunflowers Have Pointed

by Cody Stetzel | Contributing Writer

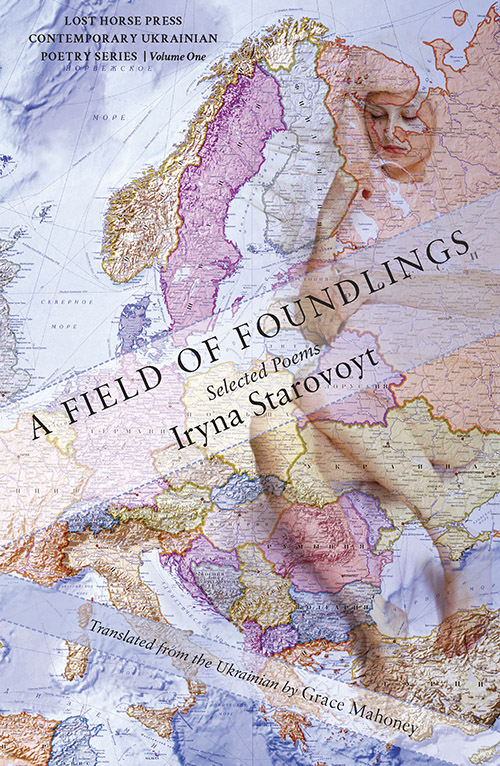

A Field of Foundlings

Iryna Starovoyt, tr. Grace Mahoney

Lost Horse Press, 2017.

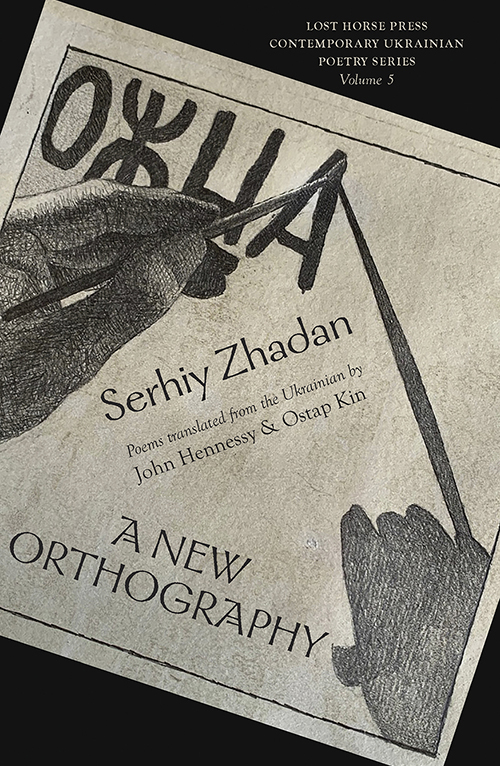

A New Orthography

Serhiy Zhadan, tr. John Hennessey and Ostap Kin

Lost Horse Press, 2020.

Years ago in a class where Heaney was being studied, the professor facilitated a discussion on what poetry’s purpose was. They placed upon the seminar table the thought that Heaney believed poetry was ‘to be the voice of contemporary people.’ And to evade the inscription of a certain ideological weight onto all poetry, I posit this as less a dictation to the to-be author and more a pleading with the forthcoming reader, the idea of reading to understand the voice of contemporary people. I believe this is something unique about poetry and its relationship with readers: poetry makes demands of those who read it.

Whereas longform prose, essays, memoir — practically any genre of writing aside from poetry — exist with expectations of thin veils that protect the readers from truths, that what they’re reading is experienced at the story’s protective distance, poetry seems to draw the reader into intimate understandings. It’s possible the recitative element provokes more I-involvement — to utter something aloud is to bring it into your own mouth, your own voice for a moment; yet more could be the disobedience to narrative and instead poetry’s distances breaking down whatever walls logic provides the reader to encounter work behind.

Poetry in translation has long been needed in this hyper-globalized world. As comfort settles in and the nurturing relationship between a story and its readers is proselytized further, poetry in translation marks a tradition of begging its readers to consider the scale of globalization and interconnectivity. These are all such grand and far-ranging claims that I believe to be true, though the particular angle that I am engaging and reading from maintains its bias and expectations. The Heaney poem in discussion, Digging, writes, “The cold smell of potato mould, the squelch and slap / Of soggy peat, the curt cuts of an edge / Through living roots awaken in my head. / But I’ve no spade to follow men like them.” The poem speaks toward a tradition of hard farmwork, broken sweats, and unquestioned attendant duty that the speaker takes up, toward the end, literally with their own pen. In this way, the poem was discussed as a form of ars poetica (“art of poetry”); that one’s cultural duties become the boundaries and parameters that spout poetry and constrain the ability to write it.

The more I read of particular cultures, regions, and languages in poetry, the more I feel like I understand what conversation adheres to, and by extension, how to connect with others. When I come across a series like Lost Horse Press’ Contemporary Ukrainian Poets, I feel the compulsion to read through it all in hopes of gaining this glimpse; what words seem to repeat across works and what do they sound like in original tongues? How granular do regional expectations of work go? Are there seeming topical overlaps that are independent of culture? The first and fifth installments in the series, respectively Iryna Starovoyt’s A Field of Foundlings, and Serhiy Zhadan’s A New Orthography, seem like vastly different shades of the same source color; or perhaps one’s a watercolor interpretation of indigo whereas the other is an acrylic version. Zhadan’s work feels like an effort at delving into language, language that shifts from world malaise over conflict or war. On the other hand, Starovoyt’s work details the macro-scale effect of conflict or war on populations — A Field of Foundlings seems to follow a path from poems speaking about the experience and recognition of the individual, to the relationships that are maintained and lost due to war, to the hope and grief for the future by pondering over the current state of Ukraine’s children.

Both poets work toward some type of defining relationship to their homeland — it feels as though there is a rebellion in granting oneself the authority to define what comprises one’s relationship with their region, nation, or people. This perspective can be seen in Starovoyt’s poem, Sometimes we think of our homeland, “Sometimes we think of our homeland / as a personal matter — / a mole, a fate, a scar of memory” as the poem continues and goes on to reminisce over who leaves and stays of a country, who gets to leave and who gets to stay. Zhadan’s interpretation of this is to look, instead, at how the poetics of a region come to be. In his poem, [The great poets of sad times], Zhadan prods toward imperialist and colonizing histories of language, that for them the purpose of language is to serve some commodifying purpose, making a border simple so as to be ownable:

“The poetics of your continent

grow from singing and grapes.

Talk about grapes, about the golden

continuity of vines that knit together

borders that look like the seams of a new

overcoat.”

This our vs. your perspective contends throughout both of their works; combative language intended to point toward the hypocrisy of an outsider relating to the experiences of people who have been conquered, or at least have fought attempts to be so. Starovoyt and Zhadan each continue with this perspective in unique ways: Starovoyt writes from the perspective of having immigrated to the United States, writing from a distance; Zhadan continues to write from the perspective of language and what the language of a freshly wounded country sounds like.

In my understanding of homeland, the regions are defined as loosely as those that I’ve lived before. Having connections — friends, family — throughout allows me to voyeuristically engage in more regions and expand the map of my homeland by following simple details like, I know my sister lives half-a-mile downhill from a wine bar in Puerto Vallarta. For Starovoyt, the network of family is the foundation for every detail of a country. That personal relationship allows one to paint, or, literally, know some connection tangibly throughout the land. She writes in her poem, Sometimes we think of our homeland:

“The history of every homeland starts from a book

of faces — of family photos with several unknowns:

some characters are scratched out, about others,

there is no one to ask.

Maybe this is why we return to stay.

For a personal matter.”

The broader theme of this poem seems to be questioning the motivation for coming from and going to a homeland: connections can be made through presence or absence, and both can inform a reader’s desire to return. Heaney’s Digging references at least three generations of men in his family that he takes after; for Starovoyt, there isn’t as clear or consistent documentation for generational settling. In order to fuel a country worth belonging to, this poem seems to make the argument that the country needs to have enough connection throughout the lands to ensure both domestic and international references can find home.

I would argue in the same intention toward belonging, Zhadan’s poem [It’s about solitude in the first place], speaks toward what language is necessary to find belonging with your country:

“It’s not enough to know the definition of words.

It’s not enough to know how to respond

to the greetings of guards by the gates.

More whimsical is the science of silence,

the art of breath,

the ability to listen to the hungry

who tell you

about morning bread,

the ability to listen until the end

to the one who hides all guilt

of humankind.”

This poem does a lot of marvelous work in defining the hostile conditions of life — the implied guards at gates, the implied hungry, the implied individuals who know definitions but not the full conversation — while maintaining the core recognition that this poem is about who can call your land home. To be Ukrainian means having a commitment to the language of plain sincerity and a blunt recognition of brutal regimes and calloused life.

Each of these books carries with it this breath of endurance — that life is spectacularly painful, and each day our choices work toward some method of minimizing this pain. Whether speaking literally of specific people — neighbors, cousins, and clerks — or speaking broader of the metaphysical element of peoplehood, the efforts both seem to spell out forms of perseverance.

Of course, a great distinguisher among suffering is time and the longevity of pain. Both Starovoyt and Zhadan twist the perils of time. For Starovoyt, she views time as a resource that, as a generation of Ukrainians continues to age through war, the bodily transformation of aging sublimates the spiritual transformation of suffering. She writes in her poem, We are antique and heirloom,

“we wait for our passing,

while transforming in body,

when it no longer grows,

except by the ears.

When sorrows grow

the soul becomes morose,”

The moroseness of a soul here blooms into a toxin that degrades the aging capacity of a generation. Zhadan’s time is a motivator, “For three years we’ve been expressing our opinions. / For three years we’ve talked standing in front of the mirror. / There’s no need to be afraid of asking tough questions. / And to fear getting uncomfortable answers” in [We’ve been talking about war for three years], arguing that the longer one needs to endure something, the less imperative there is to hide one’s vitality.

As much as Starovoyt created a work that documents personal histories of communal fleeing and bunkering, thematically her work questions with a ‘why,’ and answers with a ‘how.’ In her poem, You were only in an episode of my life, she brings up what I would argue is the seed of the work as a whole, “Let’s talk about the imperfection of a world / that wasn’t built by us.” Recognition only goes so far; as I’ve discussed this work seems bent over trying to create a defiant archive of survival. Starovyot continues belaboring this core message with a series of questions from the poem You will overwork your unskilled hands until the salt sweats,

“If everything is destined, then why fool people?

Why leave the nest? Why play the piper?

Once you find something worth holding, again

you will overwork your unskilled hands until the salt sweats.”

What I’ve called endurance and perseverance earlier, is this a reductive heroization of overwork? The point can’t be to work and strive forever against an immovable power.

Some of the final poems of Starovoyt’s work end with a similar refrain of ‘that’s how.’ In That’s how we said goodbye, “That’s how we said goodbye to our youth — silently, without devices, / waving just like an average everyday: Good bye …” there’s a resignation that flows from the rest of the book building up to the point of every action throughout life disappearing the ease of youth. This is the cold comfort of finding fewer years, months, and hours allowed for uncomplicated joy and recognizing oncoming stern nature waiting shortly behind the doors you open. Continuing shortly thereafter, The unwritten rule, brings back the ‘that’s how’ refrain with,

“That’s how they came home. Ornamental sweat

on their faces: my uncle had turned grey, and Grandpa

with an open trench on his shoulders. Grandma dreamed

of them for four years (every night) afraid that she would wash

them from her eyelids with weeping. Then she left us —”

This constant emotional translocation, oncoming and ongoingness, pervade with concern over what should arrive with a return. This refrain leads me to wonder if A Field of Foundlings is trying to ask the question: if not ease, what comes next? From both the literal and metaphysical perspectives, the book as a whole seems to construe life as a perpetual wondering at when one will be allowed to rest easier, when one will be able to rely on comfort again.

Zhadan and Starovoyt seem to be actively engaged in the same conversation. While much of A New Orthography is working toward an emphasis on cultural foundations and the question of where Ukraine rests from a philosophical standpoint, the coarse romanticization comes throughout as Zhadan tries to answer that what comes next is the opportunity that comes with rebirth. In Knights Templar, Zhadan writes,

“All who lived through the brutal murrain,

all who held onto joy and disobedience,

everyone who has survived under the heavy stars,

they rebuild a city with their hands worn to blood.”

It isn’t out of reach to find celebration in these lines, but the celebration here is not one without complications of its own. Both Zhadan and Starovoyt find solace ending with prominent hand images — hands with salt sweating, hands worn to blood — bringing forth that palpable eminence of Ukrainian struggle and determination.

Starovoyt and Zhadan seem to counteract each other in their respectively pragmatic and romantic sensibilities. At a midpoint in A New Orthography, Zhadan presents us with the lines,

“The point is to warm up among people,

from [I imagine how birds see it:].

to love this artel work of winter,

this inaudible breath of soil,

its seal.”

These lines carry such an uncomplicated charm in the grand scheme of a work rife with concerns over Ukrainian spirit, and the soul of the land. In each of these works’ intention-defining statements, they strive for almost the opposite tone of what the rest of the book entails: for Starovoyt, there’s a simple addressability all around the work that transforms into this greater world-worry of ‘what comes next?’, whereas for Zhadan the existential anxieties and concerns over emotional-spiritual capacities reduce into this unflinching spiritful statement of, ‘the point is to love.’ Contending with these two perspectives feels a bit like the salt-and-pepper entry to the taste of your meal. After all, the world continues to weep for Ukraine, and Ukraine continues to withstand waves of blood spilled on its soil. As such, some final words from Zhadan’s [And this summer also comes to an end], “Finally it heads to where / the sunflowers have pointed.”

Contending with these two perspectives feels a bit like the salt-and-pepper entry to the taste of your meal. After all, the world continues to weep for Ukraine, and Ukraine continues to withstand waves of blood spilled on its soil. As such, some final words from Zhadan’s [And this summer also comes to an end], “Finally it heads to where / the sunflowers have pointed.”

Cody Stetzel is a San Francisco resident working within electrical engineering. He has worked as the managing editor for Five:2:One Magazine and is currently a staff book reviewer for Glass Poetry Press. He received his Masters in Creative Writing for Poetry from the University of California at Davis. His writing can be found previously in the Colorado Review, Birmingham Arts Journal, Across the Margins, Boston Accent Literature, Glass Poetry Press, and more. Find him on twitter @pretzelco or at his website www.codystetzel.com

Iryna Starovoyt is a poet, essayist, and Associate Professor in the Department of Cultural Studies at Ukrainian Catholic University. Born in Lviv, Ukraine, she made her poetry debut with the book, No Longer Limpid, which was well received by critics and reserved her a place within the new generation of writers since Ukraine’s independence. Starovoyt’s work has been featured in several poetry anthologies and individual poems have been translated and published in Polish, Lithuanian, English, and Armenian, and set to music. Starovoyt was a Research Associate on the “Memory at War” project in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Groningen (2012-2013), the Netherlands, where she completed her 2014 collection of poetry, The Groningen Manuscript.

Grace Mahoney is an emerging translator of Ukrainian and Russian literature. She is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Michigan. This is her first book of translations.

Serhiy Zhadan is a Ukrainian poet, writer, essayist, and translator. English translations of Zhadan’s other work include the books of prose, Depeche Mode, Voroshilovgrad, and Mesopotamia (also features poetry) and a collection of poetry, What We Live For, What We Die For. He has received the 2015 Angelus Central European Literary Award (Poland), the 2014 Jan Michalski Prize for Literature (Switzerland), the 2009 Joseph Conrad-Korzeniowski Literary Award (Ukraine), the 2006 Hubert Burda Prize for young Eastern European poets (Austria), and the BBC Ukrainian Book of the Year award in 2006, 2010, and 2014. Zhadan lives in Kharkiv.