Interview // Transformation through Story: Heather Cahoon’s Horsefly Dress

by Jennifer Elise Foerster | Senior Editor

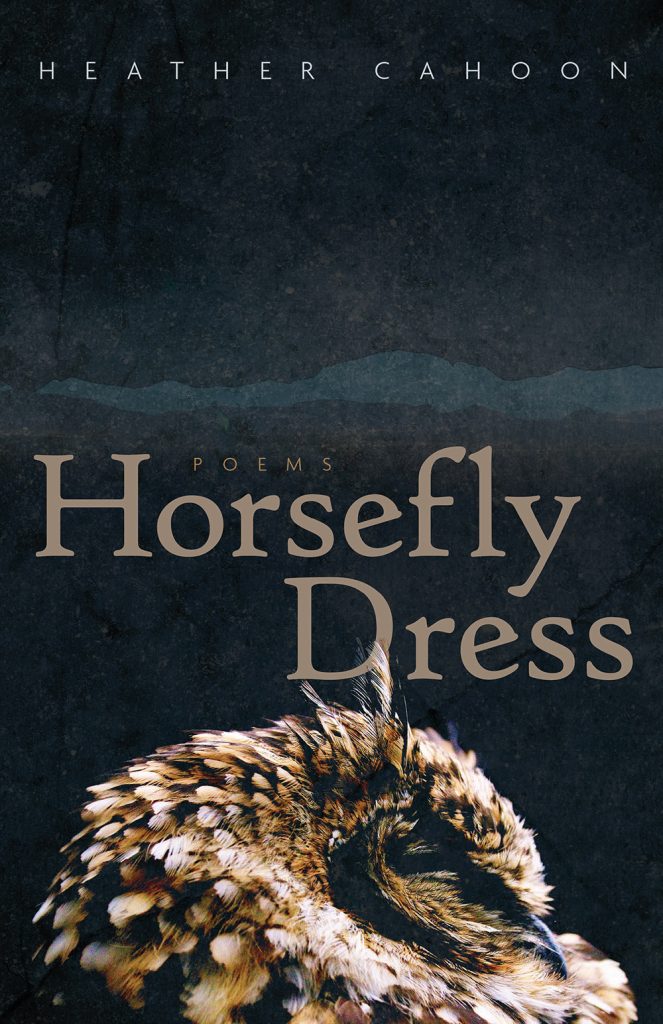

Horsefly Dress, Heather Cahoon’s first full-length poetry collection, was published by the University of Arizona Press, Sun Tracks Series, September 15, 2020. This interview is presented as part of Poetry Northwest‘s Native Poets Torchlight Series.

Jennifer Elise Foerster: Would you share a little bit about your personal path to poetry? What led you into writing poetry?

Heather Cahoon: I literally can’t recall a time when I wasn’t drawn to and writing poetry, though there was certainly a time before I knew how to write so it must have started after that. But poetry is such an intuitive genre—we experience so much of it with our bodies rather than our minds—that one doesn’t necessarily need to know how to read and write in order to appreciate or engage it. For example, a series of sounds or a set of images can provoke a felt sense of meaning whether or not we can make logical sense of it. This is one of the things I love most about poetry and is part of what keeps me writing.

JEF: I very much agree. I love that about poetry, how meaning canbe evoked by images and sounds, and how poetry emerges from intuition. I wonder, was there a particularly evocative moment that may have sparked these poems into the constellation that is now Horsefly Dress?

HC: I think there were two moments, really. The first involved becoming a mother and the ways in which that brought up various anxieties in me related to protecting my kids from the “evils” of the world, the many hurtful and horrific things they could possibly encounter. This led me to revisit my own relationship with certain instances of suffering that I had experienced, including some that I had not fully processed. A few years later, I came across Horsefly Dress’s name and was immediately captivated by her. I actually reference this second moment in the title poem, “Horsefly Dress.” I was walking and visiting with my sister, Jody, at hunting camp near a place called Revais. That area is so pretty and so quiet. There are lots of tall pine trees edging the river behind which are the beautiful, rolling, bald hills of Ferry Basin. I love it there because the whole place is characterized by a profound stillness that affects how I experience the world. It was here, with these bigger questions sort of floating around in my mind, that I began to actively seek out stories and information about Horsefly Dress and that the beginnings of the book started to take shape.

JEF: Revais and Ferry Basin sound like beautiful places. I can sense in your work an inspiration from, or a rootedness in, the natural world and landscape of the Flathead Reservation.

HC: We grew up spending so much time outdoors and in the woods. My father made a living by hunting and by selling things he could harvest from around our reservation and we often helped him in these endeavors. He would cut and sell Christmas trees, firewood, landscaping stones, and even dropped deer and elk antlers, which sometimes he would make into antler lamps and chandeliers. We also spent time as a family just driving around to pretty places for either camping or hunting and fishing or just to enjoy the peacefulness and smell of the mountains. I continue to spend time in the outdoors and the interactions I have with these places, the animals, birds, etc. often end up in my poems. Where I live now is only about twenty minutes from the southern border of my reservation and forty minutes from where I grew up. It also happens to be an area Salish and Kalispel people have lived for the last 13,000 years or more. Consequently, I cannot help but feel deeply rooted here, though I feel even more deeply rooted in the landscape of my reservation and especially in the places I’ve been going to with my family my whole life. I have a physiological response to these places—when I am there, I feel safe, my body and mind and nervous system relax and I just am. It sounds grandiose but the profound sense of presence and well-being and even wonderment I feel in these places help me remember that I need to make the most of this opportunity to experience life as me, as “Heather Cahoon,” born into this particular place and time in the history of the universe.

JEF: I love the attention in your poems to the world of flight: the wings of birds and insects, the fragile, floating webs of orb weavers and other spiders. Do you want to talk about this? As a poet, I am always intrigued by our unique “obsessions” or thematic undercurrents—the images and forms that repeat in or drive our work.

HC: You know, I have wished I could fly since I was a little girl. I don’t really think of it as often as I used to, but I’m still consistently captivated by (and a bit envious) of those things that can achieve flight. When I was much younger I often had flying dreams, which I absolutely loved, and I remember feeling periodically compelled to jump off things—our second story deck, for example, onto our trampoline or from somewhat lower heights with big trash bag “parachutes.” Later, I’d try skydiving, bungee jumping, and some “gravity defying” carnival rides like free-falling from 150 feet in the air to end in a giant sort of swooping-swinging motion that allowed us to “fly” or glide slowly back and forth over a pretty-sizable patch of ground. Relatedly, as a kid I loved swinging sky-high on swing sets with my eyes closed waiting for that split second of weightlessness before being pulled back into the opposite direction. To this day, I cannot be amidst really strong wind without closing my eyes and out-stretching my arms in a way that replicates the sensation of flight. There is such a sense of freedom in even momentarily feeling yourself weightless, of escaping, I would say, both the physical and emotional weightiness of being alive/human. As a child I thought of becoming an astronaut, though as I’ve grown older, and especially after having kids, I’ve come to prefer the feeling of rootedness. I suppose I now sort of vicariously live out my flight dreams through birds, which I have always loved, especially songbirds, birds of prey, and everything in the Corvidae family. Besides their flying abilities, I’m very drawn to their movements and behaviors, their hollow-boned bodies, their different voices and songs, the textures and colors of their feathers, everything about them. Because they occupy the space between earth and sky, between terra and the celestial worlds, for me, birds represent both the inaccessible and the accessible, which is really the unknown or the place of possibilities.

JEF: I appreciated how this book weaves several threads into its story-making: the dreams, the Salish-language titled poems, the Coyote and other traditional story poems, and the personal family narratives. I also noted that these many threads were intertwined within poems as well. How did you determine this book’s choreography?

HC: In the very beginning, I was really just writing—as you know, one never knows what’s going to come out onto the page—but I very quickly realized that this was different in terms of subject matter. Because Horsefly Dress and her family were making their way into the poems, I met with the Director of our Culture Committee to ask about the appropriateness of writing about them and especially in ways that veered from the traditional stories in which they appear. During the course of our visit he encouraged me to proceed but told me to write with the awareness that there is a difference between creating and receiving information. After that, I never wrote without first smudging and praying that I would hear only the words that needed or wanted to be written and that my community or others would benefit from reading. That said, by no means do I think Horsefly Dress is some sort of “divine revelation,” but I do believe that artists are often, at some level, tapped into the collective consciousness of their broader communities. And I think that it makes sense that as part of a particular sociocultural ecosystem, the stuff floating around in one’s conscious and unconscious mind would reflect a variety of inputs from this wider environment. So, to answer your question, I would say I just trusted the process and was open to “whatever inks itself onto the page.”

JEF: I felt a strong theme of shifting or transformation/transmutation throughout these poems, as in “The Hawk Who Wears an Owl’s Face,” who “flashes into beings” and “splits into two” and the speaker releasing bluebirds from her throat, as just a few examples. Is shifting or transformation a theme that emerges from the oral traditions these poems are engaging? Is this a theme or poetic aspect that you feel is central to your work?

HC: Transformation is definitely a theme in many of our oral traditions, especially our Coyote stories, that also carries over into this collection to become a central theme. Horsefly Dress is a sort of chronicling of my personal experience of processing various instances of grief that I had been carrying with me and how pursuing information about Horsefly Dress led me deeper into our oral traditions. Among other things, a lot of the stories help normalize the idea that suffering is not only a natural part of life but that it can in fact serve a higher purpose in terms of its transformative powers, which I’ve talked about in more depth with Shriram Sivaramakrishnan in a previous interview for Poetry Northwest. Likewise, it is oftentimes only as we work through our suffering that we are able to acquire the skills necessary for coming out the other side of the experience. In a metaphorical sense, this kind of personal transformation constitutes a rebirth into a new state of being wherein we can no longer be aggrieved by the very thing that previously caused us to suffer. In our stories, these “things” are literally referred to as naɫisqélixʷtn, or people-eating monsters, because they threatened to consume or gravely harm us. Today, these monsters can take the form of things like heartbreak, addiction, self-doubt, etc. The stories show us that we can play a very active role in disarming the things that threaten to destroy us and we can do this through our ingenuity, perseverance, and being open to listening and learning from the lessons of those who came before us. I think it can be very helpful and empowering to contextualize our experiences of suffering in this way and it was partly these ideas that helped me process some of my most challenging moments and led me to write this book.

JEF: Heather, you are a scholar and respected leader in the fields of federal Indian policy. You’ve launched a research think tank at the University of Montana, the American Indian Governance and Policy Institute (AIGPI). Can you talk about the intersection between your work researching tribal-level policies, your commitment to civil justice issues and tribal socioeconomic health, and your work as a poet?

HC: There are definitely some intersections when it comes to subject matter and, to a lesser degree, maybe also in the creative aspect of writing in general; whether it’s poetry or academic writing, the writer is bringing something from nothing into existence. In terms of the overlap in content, some of the poems I write stem from work-related encounters I have with different tribal leaders, communities, or landscapes. Some of the poems also speak to broader socioeconomic issues or the outcomes of federal Indian policies, while others attempt to illuminate or communicate what I think are some of the most beautiful aspects of different tribal philosophical beliefs. Despite these intersections, engaging in both pursuits often feels quite challenging because I’m forced to choose between which endeavor I’ll pursue within the limits of my available time. Thus, I regularly end up having to work on poetry outside of my “real” job, which has probably influenced my long held idea that a poet is something I am while a policy scholar/professor is something I do. As unfortunate as this feels, I do think that my seemingly divergent interests or professional pursuits are a lovely complement to each other, in that I can get mentally caught up in my policy research and teaching, which tend to be quite cerebral, but writing poetry counters this state by bringing my awareness to the present moment and grounding me in a bodily experience of time and place, which I think is really important in maintaining one’s mental and even physical health.

JEF: Are there particular authors, poets, or figures who have significantly influenced your poetry?

HC: I read mostly academic research and scholarly texts but when I read something outside of that it’s often work by Native poets, and especially Native women poets. Like everything one is exposed to, I’m sure their writing influences my poetry in a very subtle or subconscious way. There are several poets whose work has influenced my writing in a way that I’m much more conscious of; this includes dg okpik’s Corpse Whale, Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas, Sherwin Bitsui’s Flood Song and Dissolve, Tanaya Winder’s Words Like Love, and Joy Harjo’s Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings. Each sparked either a line of poetry, an image, or a formatting idea that appear in Horsefly Dress. Beyond this, I would say that the encouragement of my early teachers, particularly Patricia Goedicke and later Sandra Alcosser, also significantly influenced my poetry in that they gave me the confidence to keep writing and to eventually take my writing from a private to a public arena. Making that jump can be difficult and I’m really grateful for the mentoring and assistance I’ve received from other poets who’ve already “made it” and who are willing to help uplift and promote the voices and work of others.

JEF: Thank you, Heather—your work will certainly be inspiring and uplifting to others.

—

Jennifer Elise Foerster is the author of two books of poetry, Leaving Tulsa (2013) and Bright Raft in the Afterweather (2018), and served as the Associate Editor of the recently released When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through: A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry. She is the recipient of a NEA Creative Writing Fellowship, a Lannan Foundation Writing Residency Fellowship, and was a Wallace Stegner Fellow in Poetry at Stanford. Her poetry has recently appeared in POETRY London, The Georgia Review, Kenyon Review and other journals. JEF currently teaches at the Rainier Writing Workshop and is the Literary Assistant to the U.S. Poet Laureate, Joy Harjo. She Foerster grew up living internationally, is of European (German/Dutch) and Mvskoke descent, and is a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma. She lives in San Francisco.

Heather Cahoon is a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and is the author of the 2020 poetry collection, Horsefly Dress, published by University of Arizona Press. Her poetry has been most recently anthologized in Living Nations, Living Words: An Anthology of First Peoples Poetry (2021),and When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through: A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry (2020). Her chapbook, Elk Thirst, received a Merriam-Frontier Award from the University of Montana’s College of Humanities and Sciences in 2005, and in 2015, she received a Montana Arts Council Artist’s Innovation Award. Heather received her MFA from the University of Montana in 2001, where she was a Richard Hugo Scholar, and an interdisciplinary PhD in history, anthropology, and Native American Studies. She is Assistant Professor of Native American Studies and Director of the American Indian Governance and Policy Institute at the University of Montana, and works as a state-tribal policy analyst for the Montana Budget and Policy Center. She lives in Missoula.