Raveling the Unraveled

by Rob Carney | Contributing Writer

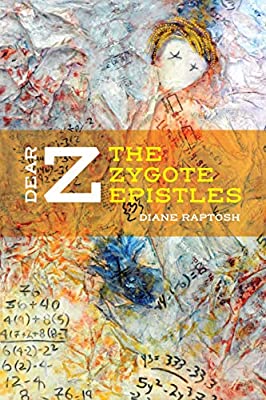

Dear Z: The Zygote Epistles

Diane Raptosh

Etruscan Press, 2020

In Dear Z: The Zygote Epistles, the third book of a poetic trilogy, Diane Raptosh gives us cultural X-rays and diagnoses along with visions of a better way. Raptosh started this project with American Amnesiac (Etruscan Press, 2013). In that collection, her speaker can’t make sense of who he used to be now that he’s become a tabula rasa. Apparently he used to work for Goldman Sachs, which, with his new eyes, he sees as a human tar pit. In the middle book, Human Directional (Etruscan Press, 2016), the speaker is likewise perplexed, and that awful job—holding and spinning an advert sign to point passing cars toward one business or another, being what’s called a “human directional”—is a loaded metaphor. It’s a way to show us where we are, where we’re going, why it’s not good, and why we need to change. Now, in the trilogy’s finale, the speaker is a soon-to-be great aunt, and she’s speaking to the future. Luckily, readers get to hear her too.

Hear what? First of all, voice. Raptosh’s voice is full of sonic mojo. And it kaleidoscopes. It’s as if Lucky’s “Think Speech” in Waiting for Godot went dancing with Janis Joplin, and they collided with a manic Jack Kerouac and the owl from that 70s Tootsie Pop commercial, after which they all sit at the bar and make remarks about everyone texting. “Zygote,” the speaker says to her future grandniece,

in our age thinking is seen

as a lump of cold lotion, mostly a thingtoo mutant-dreamy to do. Do you bereave me? Would you

agree to the use of cookies? Don’t you just hate

when the no-good knuckles over the truth? Give me

your nevermore hand: Let us become oblong

sans-nation transitionals.

It’s a good critique and a better wish, and she follows it up soon after with this:

Dear Z,

The collective brain’s

migrated

to the spectacle pit,

the world in its

permanent warfare suits,its plague of blue angers,

reality’s X-outs[. . .]

Would you rather real-life swim

or live-stream?

That last bit is all about nature—about what’s natural versus not—and it’s key to the book’s whole project. Here the speaker asks the essential question in the form of clever oppositional wordplay, and then hopes the answer—from her future grandniece, and from the present-day reader—is yes to real life.

In the book’s shortest letter—just a single line long—she puts it this way: “Dear Zygote, // What we call the world is also—perhaps more accurately—called the without.” For the speaker, this world-as-without formulation means that life is too full of denial and absence and lack of. It’s strong and succinct writing, like a rock chucked in a pond, after which the ripples keep meaning and meaning: If the world is “the without,” then the world is separate from our inner selves, from our thoughts, souls, and interior monologues. In fact, it’s what’s getting in the way of our inner selves.

And Raptosh knows this. It’s what she’s been telling us across her last three books.

This hard truth from her speaker is just the beginning, though. The book moves from there to concern. After a lifetime of brains and experience, the speaker has sussed things out, and she doesn’t want our current lack of (lack of ethics, lack of justice, lack of environmental stewardship) to be how things remain in her grandniece’s future. She sees it all clearly, and says:

Dear Z,

you’re just an old flit

off the infinite-quickie.

You’re this age’s latest, for realz—

where latest means newness’s

baby.[. . .]

Pretend that

you know the drill

of the shell corporations,

those not-anywheres, those surpluser nations’

distant money troves. Ho! The shit things

we think to twiddle

our thumb-quicknesses on:

Reality jousts its own touchscreen.

She sees it and says even more matter-of-factly:

Warming polar zones means

good news for a fleck

of red alga, but that’s about it.

And she brings these concerns together with others—for instance, America’s epidemic of mass-shootings—but also tells her future grandniece why she won’t give up:

Dear Z,

[. . .]

I can hardly write when I think

of what happened in June

in Orlando’s Pulse Nightclub,

but it’s worse to refuse to.

Does she mean it’s worse psychologically; as in, not writing would deepen the despair? Or does she mean it’s worse sociologically; as in, not writing back against everything that’s wrong is a sin of omission? Probably both, and then she continues on from there.

In section “III: Dear Zeitgeist,” we get lessons in hope to counterbalance the world’s stupidities and injustices. For instance, she writes, “Dear Rich Jam, // [. . . ] I’ve come to feel // vaguely parental. It’s pre-natal’s anagram. / As verse is serve’s.” For instance, she writes, “Dear Z, // New Zealand views animals by law / not as objects but sentient beings.” And in section “IV: The X Y and Z’s,” we get music history, logic lessons, a whole gumbo of pop culture, and a wild language parade from start to finish, but we also get this calm and well-placed island to rest on: “Dear Z, / Your Georgia aunt could not pronounce idea / in such a way it did not end in ear.” Of course, ideas begin with the ear too—the Alpha and Omega—and Raptosh’s speaker is making it clear that thinking is inseparable from listening. We need to listen to the lessons of history (X), and listen better in our own present time (Y), and listen to what’s waiting in the future (Z) because the future is asking us to please stop ruining it all in advance.

“Section V: Forgive, Relieve” presents us with how to avoid that. Turns out, it isn’t that difficult. “To counter this,” the speaker says, “everyone must come to see // all residents as members of my group.” Why that still needs saying in 2020, and why it takes Dear Z: The Zygote Epistles to paint it like a sign and nail it to the wall, is hard to fathom. Raptosh fathoms it plenty, though, and has her speaker repeat it once more in another way, saying that we must come to see that “the pain of others” is “our severest strand of anguish.” Then the rest of section V goes zooming, accelerating, and that pace helps to set up the book’s closing contrast where, as if we’re finally coasting downhill, the speaker gives us this:

Dear Listen,

I’ll give you how some scenes in life

might still fall in line—

but at the brink level

of emblem or myth.

And how even an unpeopled Idaho

may end up this wow-state to live

if you’re big into seas of dry land

and open-vowel euphony policies,

where the poet is known to be

cowboy of wild rye and the open page,

riding out trails on a word called horse,

raveling its earths in some human disguise.

Now that’s a vision to pass on to a grandniece: the belief that the next generations might still know how to be open, natural, and wild. And it also rounds full circle to the book’s beginning. There, in the opening letter, the speaker began by saying, “You cannot undo // the done-unto-you, / but you can forgive it.” And here, in the final letter, we see that forgiveness being demonstrated. The real is not the ideal. Not yet and maybe not ever.

But it can try.

—

Diane Raptosh’s fourth book of poetry, American Amnesiac (Etruscan Press) was longlisted for the 2013 National Book Award as well as a finalist for the Housatonic Book Award in poetry. The recipient of the Idaho Governor’s Arts Award in Excellence (2018), she is a three-time State of Idaho Literature Fellow. She has also served as Boise Poet Laureate (2013) as well as the Idaho Writer-in-Residence (2013-2016), the highest literary honor in the state. An active poetry ambassador, she has given poetry workshops everywhere from riverbanks to maximum-security prisons. She teaches creative writing and directs the program in Criminal Justice/Prison Studies at The College of Idaho.

Rob Carney is the author of seven books of poems, most recently The Last Tiger Is Somewhere, co-written with Scott Poole (Unsolicited Press, 2020), Facts and Figures (Hoot ’n’ Waddle, 2020), and The Book of Sharks (Black Lawrence Press, 2018), which was named a finalist for the 2019 Washington State Book Award for Poetry. His first book of creative nonfiction, titled Accidental Gardens (Parndana, South Australia: Stormbird Press) is forthcoming later this year. Carney writes a featured series for Terrain.org called “Old Roads, New Stories.” He is Professor of English and Literature at Utah Valley University and lives in Salt Lake City.