Taking Measure: Martha Silano and Laura Da’ in Conversation

Introduction by Martha Silano

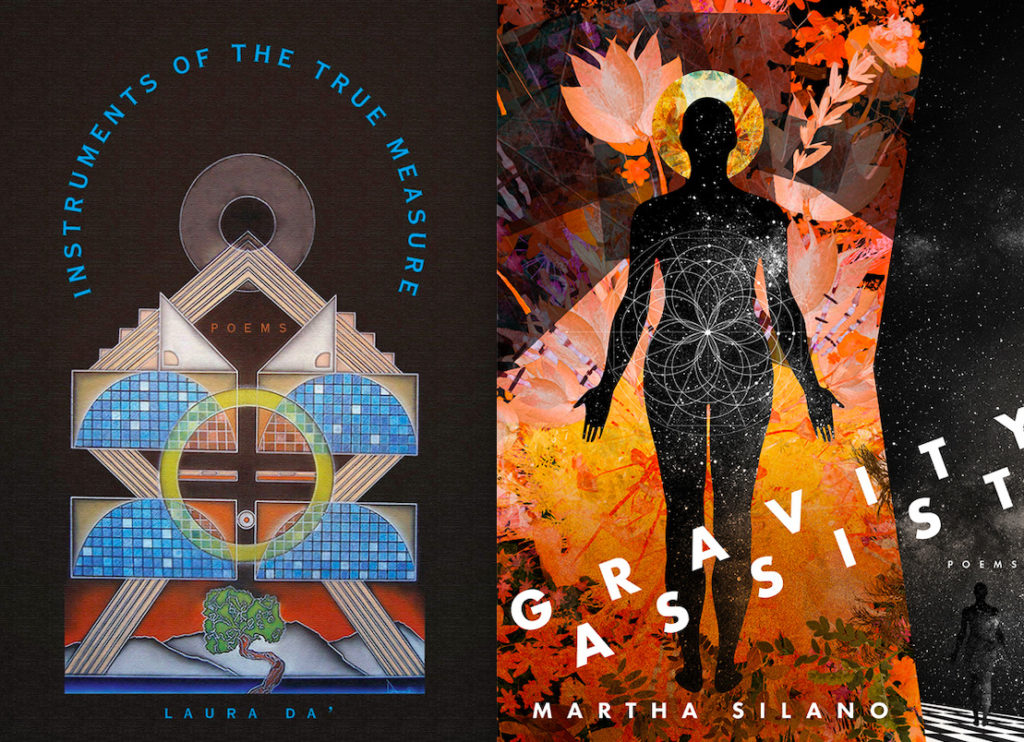

In the summer of 2019, I reached out to Laura Da’ to inquire if she might be interested in doing a co-interview. Laura and I had recently read together in Bellingham and Seattle, and I wanted the extra nudge to sit down and carefully read her amazing Instruments of the True Measure (University of Arizona Press, 2018), which, soon after I finished reading it, was very deservedly awarded the 2019 Washington State Book Award. After we both had a chance to read each other’s books (my Gravity Assist appeared from Saturnalia Books in March 2019), we met for coffee to get better acquainted, ask a few nuts and bolts-type questions, and marvel at the discovery that our books share a parallel theme: the act of measuring as a way to calibrate ancestral and generational trauma. Given the fact that we are both working parents, we decided to conduct our co-interview via email. I sent Laura her first question in late July, and we continued in this back-and-forth manner through early 2020.

Martha Silano: From the first poem of your newest collection, Instruments of the True Measure, I found myself captivated by the way you use startling metaphors to talk about the forced movement of the Shawnee from the Ohio Valley to points west. The opening poem, “Nationhood,” uses the birth of a child as a metaphor to characterize the obliteration of one frontier and its people. With the word frontier, our attention is called to the fact that America was not “nascent” when it was “discovered” by white European settlers, that it’s a mistake to think of the original residents as uncivilized. They were not ipso-facto nomadic or not noble savages; they, too, lived on a frontier: “Our new [breathing] bodies obliterate old frontiers.” It’s a subtle, significant word choice. You make similar key word choices all throughout this book—ones that cause the reader to rethink the Westward expansion story. Can you share a bit about the thinking behind the use of language, the descriptions of the land and the two main characters—Lazarus and Crescent—as if they could both be native (Crescent is white; Lazarus is Shawnee)? Was it an intentional decision to make it difficult for the reader to know which boy is native and which one is not?

Laura Da’: Thank you for your close reading and intriguing questions. I imagine particular words in this collection as pivots or turning gates. They have rich, but often limited connotation under the context of the dominant white, settler-colonial perspective. Narratives sometimes fossilize these words into protective fortresses around American mythology. I want to confound words like frontier, civilization, and nationhood and pull down that foundation.

I’m so pleased that you noticed the ambiguity in the characters of Crescent and Lazarus. I see that as a kind of turning doorway as well. Some readers understand clearly and immediately that Lazarus is Shawnee and Crescent is white while others do not, and some have read them as two facets of the same character. One of my objectives in engaging with these figures was to hold some honesty for the complications of my own ancestry, but another was to juxtapose the ways that each figure’s worldview informs the way he moves across the land.

I’d like to begin with the first poem in your collection as well. Your book has been my constant companion over the summer. In addition to its literary delights, it has become a marker of a transitional period for me as a parent. Your book’s critical engagement with the delicacy and complication of family life has been such a compelling point of reference. I’m finding that multiple readings are exponentially rewarding. In your first poem, “Song of Weights and Measurements” you make an intriguing interrogation about the ways a culture measures being a reflection of that time and culture. What made you select this poem as the first one of your collection?

Martha Silano: I am intrigued and drawn to this idea of particular words as swinging gates or pivots in your collection, words as “protective fortresses” (what a great way to put it) of the Westward Expansion story. Come to think of it, Western Expansion. Talk about a euphemism! I love how your book forces me to call into question the standard history lessons provided in our schools, at least while I was growing up in the 1970s (hopefully things have improved?). You asked about the first poem in my book, “Song of Weights and Measurements.” Just as you spoke of “fossilizing words,” as I worked on this poem I became interested in excavating old measurements—for instance, the furlough, which is the length a team of ox could plow in a day. I became giddy as I devised ways to play with the sounds and sense of these extinct or scientific words of measurement—making a verb out of joule (“For I have jouled along . . .”) and finding a way to use the language of horse measurement (a horse is measured, believe it or not, in hands), along with the word withers (the ridge between the shoulder blades), but a different meaning (to lose vitality/to shrivel). Often I work with a list of terms, then begin drafting a poem, inserting the terms as I move along. This was the case with this poem. When I began drafting this poem, I had no idea where it would end up. It seemed like one magic moment after another as I found out there was actually a measurement called the fother: a cartload or quantity of lead. I also did not know I would end up referencing the month I spent in the inpatient mental health facility at Harborview Medical Center, recovering from postpartum psychosis after the birth of my son. Was it Robert Frost who stated “No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader”? This is definitely one of those poems I had no idea would end where it does: “forty rods from your chain and bolt.”

You refer to this poem as “an intriguing interrogation about the ways a culture measures [and that measuring] being a reflection of that time and culture.” I think I get what you’re saying—in many ways, we measure differently now than we did in the pre-tech era. Our measurements have gotten smaller, for one. There’s the nanosecond, for instance: one billionth of a second. There wasn’t much use for this measurement in the Middle Ages, but it’s become increasingly necessary to break time into smaller units to measure things like pulsing lasers.

Why is this poem the first one in the book? First, because measuring oneself against another, being measured and coming up short, drags a person down. The speaker tries to live up to her father’s expectations but can’t. Instead of toppling “the trudging, trenchant cart,” she shirks off the yoke. Second, because the poem introduces the reader to the central theme of the book: for a gravity assist to occur, the object that will be flung out into the far reaches must first come in close contact with the body it orbits. Metaphorically, the speaker in this book cannot escape until she examines the forces that kept her in place.

Speaking of measurements, I’m interested in the poems in your book that directly address surveying: “Mapstick” and “Correction Lines,” along with the title poem. Where did you first come up with the idea to weave the coordinates and language of surveying into your poems, and make it one of the through-lines of your book? In what ways did it help you to tell the story of a radically changing frontier?

Laura Da’: I’ve been fascinated by your response for the last few months. I keep reading and re-reading your connection between the word fother and your sharing of your postpartum experience alongside your reflection on the nature of a gravity assist and its imperative to examine a force of inertia or resistance. I’m amazed by that and have been thinking about it and feeling a sense of deep appreciation for what you have said.

The poem “Despite Nagging Malfunctions” begins and ends with the image of a spoon. It seems to flash in the lines like a trickster. Sometimes it seems like a tiny domestic menace, and other times it stretches to cradle the universe of the poem. As I read the poem “Instead of a father,” the images, sounds, and form all come together to make me feel the abrasion of the pumice, the barking dogs, and the fine particles in the blood. I mention these observations because I see them as a powerful indication of your collection’s prolonged, attentive, and singular treatment of the domestic, homes, children, parents, family, and memories. As a poet, I’m wondering how these synchronous images, sounds, and movements came together and how you developed them so subtly in your poems.

I became interested in surveying during a trip in 2008. I was travelling with around one hundred fellow Shawnee tribal members to areas of cultural significance in the Ohio Valley. Our people were forcibly removed from that area in the 1830s following the Indian Removal Act, and it has only been in the last decade that the tribe has had the means to return, albeit for a week at a time.

It was a powerful week. I noticed as an aside that America marked its official “Point of Beginning” in the heart of Shawnee Territory. I started to research more and formatted a kind of working poetic thesis that surveying was a critical preemptive step to American genocide. In my family history, I have surveyors and leaders who actively resisted surveying on tribal land. More than anything, I used the concept of surveying as a symbol or worldview to lyrically riff against and resist.

Martha Silano: Wow, to travel with a large group of Shawnee tribal members through the Ohio Valley, your ancestral homelands. That must have been very intense! Powerful, as you say, but I imagine you felt a whole array of emotions as you visited cultural sites—anger, sadness, grief, the pain of ancestral trauma, to name a few, though please correct me if I’m off base. Also, I’m curious about what you said with regard to tribal members having access to their homeland. Is it only in the last decade the tribe has been permitted to return to their land, and only for a restricted amount of time? This feels terribly wrong to me.

It sounds like you had a lucky accident when you just happened to notice that the “Point of Beginning” is in the heart of Shawnee Territory. Is that when you began formulating your thesis about the link between surveying and the genocide of indigenous Americans? I am also fascinated by the fact that your ancestors include surveyors and leaders who resisted surveying tribal land, and that your book is carrying on that same resistance. Does helping to raise awareness about the American genocide provide a sense of healing or, if not healing, a satisfaction in knowing you are dispersing essential (and often neglected) knowledge?

As for Gravity Assist’s focus on the domestic, I wanted this book to mirror the steps of an orbiting body before gravity assist, en route to gravity assist, and after the assist has occurred. To apply the math and science of how to get a spacecraft out past the solar system to a life. My life.

The before poems deal with my family of origin. The middle section contains poems that signal, in scientific terms, an adjustment into a stable orbit, where the speaker is able to observe the world and its creatures, a world both beautiful and in peril. The final section brings the speaker closer and closer to escape velocity – the vamoose out of the hold the dysfunctional domestic had on her. You ask how these various images—spoons, pumice, chained dogs—found their way into my poems. As I write, memories pop into my head. I figure I only remember about 10% of anything I’ve read, heard, or seen, but what I recall is very clear. Those are the memories that eventually find their way into my poems—the ones I just can’t forget.

Laura Da’: Traveling to my tribe’s ancestral homeland in the community of my fellow tribal members was a powerful experience. In a way, it was like a birth—painful, transcendent, oddly mundane (my roommate kept stopping up the motel toilets) and unpredictably moving. I cried a lot and I fought a lot and I ate way too much. I see it as a powerful encounter that clarified my sense of urgency as a poet. There are ways that the violence of the settler state saturated in war erased my path to my own ancestors, so the ambiguity of poetry becomes a gesture to the ruptured integrity of the question of who I am and where I come from.

Surveying is a lens. It allows me to engage with the way that worldview can be a tool of supremacy and exile. I see measuring land as a fundamental removal from the land itself, and thus the breaking of a whole system into parts. A broken whole facilitates inhumanity. That trauma ripples across the generations. Blood quantum is a system of measurement closely aligned with genocide and erasure. I have a government document that shows the percentage of my Shawnee blood, which is to say that the government has broken me into parts on paper. Because I have read that paper, my mind has been assaulted by this severing. I may slide into a shifting territory of affected objectivity when I am writing and researching or holding the concept of my own self hood, and then the pain of it hits me. I can’t look without it hurting and I can’t stop looking.

Martha Silano: What a gorgeously poetic and poignant articulation of the effect your journey back to Shawnee territory had on you. I am floored by your ability to move in and through objectively assessing the facts of genocide and feeling those effects in your own body. I have learned so much from your book and so appreciate the chance to learn more.

—

Martha Silano has authored five poetry books, including Gravity Assist (Saturnalia Books, 2019), The Little Office of the Immaculate Conception, winner of the 2010 Saturnalia Books Poetry Prize and a Washington State Book Award finalist, and Reckless Lovely (Saturnalia Books, 2014). She also co-authored, with Kelli Russell Agodon, of The Daily Poet: Day-By-Day Prompts For Your Writing Practice.

Laura Da’ is a public-school teacher and the author of the collections Instruments of the True Measure (University of Arizona Press, 2018) and Tributaries (University of Arizona Press, 2015), winner of the 2016 American Book Award and the chapbook The Tecumseh Motel. Her work has appeared in the anthologies New Poets of Native Nations (Graywolf Press, 2018) and Effigies II (Salt Publishing, 2014). A member of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe, she received a Native American Arts and Cultures Fellowship. Da’ has also been a Made at Hugo House fellow and a Jack Straw fellow. She lives in Newcastle, Washington, with her husband and son.