Don’t Drink the Black Milk

by Hilary Plum | Contributing Writer

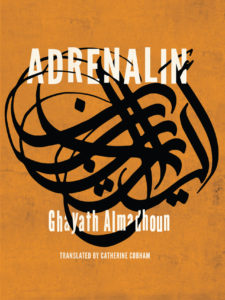

Adrenalin

Adrenalin

Ghayath Almadhoun

Action Books, 2017

Ghayath Almadhoun’s Adrenalin is about living and dying in cities. I say “about” meaning not just the subjects with which the book is concerned—the cities of Damascus and Stockholm—but that the book circles or nears these cities, moves about them, approaches and reverses direction (about face). No matter your direction somehow the city defines your movements, a city at once here and beyond you. Almadhoun is, his bio tells us, “a Palestinian poet who was born in a refugee camp in Damascus in 1979”; “[he] has lived in Stockholm since 2008.” Adrenalin is his first appearance in English, in Catherine Cobham’s translation. This book maps the distance between these two cities: the violence that distance allows, the violence through which that distance is maintained, and how the poet’s own body may breach it: “I’ve cleaned my room of any trace of death / so that you don’t feel when I invite you for a glass of wine / that despite the fact I’m in Stockholm / I’m still in Damascus.”

The distance between the European cities to which in recent years refugees flee and the cities from which they are fleeing is marked by the infinitely violent history of colonialism. The poem “The Capital” begins “–What’s the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo? / –Antwerp.” By the next page the Syrian civil war is here, too, “in this city that is nourished on diamonds,” where “a taxi stops when its driver is killed by a bullet from a sniper in Damascus / in front of Antwerp Central Station” and “terror stops on PlayStation.” For some, war takes place on a screen or in a far colony, obscured by gem or game; for others, in the bullet that finds them: “I was exploring the difference between revolution and war when a bullet passed through my body…” (“The Details”).

One could say that Adrenalin is “about” the ongoing war in Syria and the Syrian refugee crisis, but only if the word “about” keeps observing a distance between the subject and the act of nearing that subject. Maybe the distance of “aboutness” is what the vehicle of a metaphor is meant to cross, or the distance—vehicle from tenor—in which a metaphor remains suspended. The book’s first poem, “Massacre,” explores this state of suspension, of what remains unreachable—a problem that metaphor proposes and death accepts: “Massacre is a dead metaphor that is eating my friends, eating them without salt. They were poets and have become Reporters With Borders…” The tone is wry and merciless, though the lack of mercy belongs in reality to the subject; the poet’s speech merely approaches it. (And here as throughout the book we appreciate Cobham’s translation, its keen irony and efficient turns.) The “dead metaphor” metastasizes through our politics, ever more lethal: “Massacre opened the door to them when other doors were closed… Massacre is the only one to grant them asylum regardless of their backgrounds.” Massacre claims the poet’s friends, though they belong to it only through resemblance, simulacrum; they are lost to it so that they may never be found under its sign: “Massacre has the same dead features as them… Massacre resembles my friends, but always arrives before them in faraway villages and children’s schools. // Massacre is a dead metaphor that comes out of the television and eats my friends without a single pinch of salt.”

In this last line, the expected distance reverses: the war that is killing the people you love isn’t over there, as you watch it onscreen. Somehow it originates in the screen, in the idea of itself as spectacle, and that is how it comes to kill them—though without even the pleasures of spectacle, without even a pinch of salt. You are left here, complicit, the screen still before you. In this book acts of representation are never far from acts of real violence; the poet proclaims complicity and incrimination even unto the carnivalesque. “Throw away Rimbaud’s poems and bring on the slave trade,” the poem “The Details” concludes, in a chilling, incantatory list that places the book in our hands in a history told in shades of realism and surrealism, moving from the Renaissance to the Holocaust to the gulag to the AIDS epidemic, and ever on. “Throw away Picasso’s Guernica and bring on the real Guernica with its smell of fresh blood, / We need these things now, we need them to begin the celebration.”

Throughout Adrenalin, Almadhoun incisively denies the customary means to keep one’s distance from the hell of war, cutting satirically into the sentiments that allow us to live comfortably in relation to that screen, to reality as familiarly represented. In “We,” those who suffer and die onscreen apologize relentlessly to potential viewers: “We, who are strewn about in fragments, whose flesh flies through the air like raindrops, offer our profound apologies to everyone in this civilized world, men, women and children, because we have unintentionally appeared in their peaceful homes without asking permission.” The poem undercuts the comfort we might seek in the idea that our acts of bearing witness elevate us into agents of change, humanitarian interventionists: “We are the things you have seen on your screens and in the press, and if you made an effort to fit the pieces together, like a jigsaw, you would get a clear picture of us, so clear that you would be unable to do a thing.” To bear witness truly to this suffering, the poem proposes, might mean you could neither go on with your life as you know it nor do one thing to help anyone. In the agony portrayed in this story you may be no protagonist.

Almadhoun also assaults the etiquette of the current war and crisis in the poem “I Can’t Attend,” which considers reasons the poet might offer for his absence from Syria, for declining to attend the war. Thus the poem undermines the ways we conceive of the safety of the refugee’s destination in relation to the home from which they have been “saved”—how through this rhetoric one city is cast in light, the other in darkness:

In the North, close to God’s boundary wall, enjoying a developed culture, the magic of technology, the latest achievements of human civilization, and under the influence of the drug that grants safety, health insurance, social security and freedom of expression, I lie in the summer sun as if I am a white man and think of the South, contriving excuses to justify my absence. …

Yes, I can’t attend, for the road between my poem and Damascus is cut off for postmodern reasons: these include the fact that my friends are ascending to God at a rapidly increasing rate, faster than my computer processor, while other reasons relate to a woman I met in the North who made me forget the taste of my mother’s milk…

This woman appears throughout, less an individual character than a figure of the beloved, one who comes to stand in for the city of Stockholm itself. Poignantly she emphasizes how displacement replaces. One’s life was about one city, and now it is about another; even new memories of love come at the expense of what they supplant. The poem “The Details” describes a “Palestinian refugee… forced to emigrate to a place where he met a woman who was like memories”—and this resemblance, we see, may be not wholly gift, but loss of the real thing. The long poem “Schizophrenia” moves across Flanders fields and through the history of chemical warfare—a history now being written into “the heavily populated suburbs of Damascus,” bombarded with sarin gas: “a moral earthquake striking the world.” The poem travels back and forth between Ypres, Stockholm, and Damascus, between this breadth of history and the intimate facts of the poet’s own life, “the Palestinian-Syrian-Swedish refugee,” “the Palestinian distributed over many massacres, standing here naked, trying to wear my poem in the hope that it will hide my wounds.” A section titled “Stockholm” presents this woman and this love affair fully, in terms that emphasize what’s forgotten, what’s not cared about, what’s slipping away:

The main thing is that I no longer care about trivial details: to this moment I don’t know the number of the bus that goes to your house. All the same I reach you every time and slip into bed beside you. I no longer remember how your body changed my understanding of places and directions. … I sweat until Arabic poems get mixed up with Swedish poems in my head. I no longer care about trivial details, about a city without you in it, nor even about a homeland if you’re not there.

So the poet loses his homeland anew, by wanting to lose it, by loving something else instead. Later in the poem this escalation of loss appears differently, as the poet considers his own safety in Stockholm (“The city is calm,” the poem notes, just as it has recorded the sarin gas exploding outside Damascus): “Death cannot give me a homeland, and if it can then I don’t want it.” Any poem is complicit in this displacement and replacement, the ways that writing “about” reinscribe the distance from the real thing “with its smell of fresh blood”—as in these harrowing lines in “The Capital”:

let’s call things by their names

books are the graveyards of poems

houses are concrete tents

[…]

my room has fallen in love with your green shoes

I drown in you as Syrians drown in the sea

oh God

look where the war has taken us

even in my worst nightmares it never occurred to me

that one day

I would say in a poem

I drown in you as Syrians drown in the sea

In “Black Milk,” the book’s final poem, the devastation of this dilemma reappears in the form of what the poet tries not to remember, tries not to think about. This line of thought leads us with ferocity from the recent past into the present—“In those days we knew that he was going to kill us all, but we didn’t know that the world would stand by in silence”—into the memory of “how the Europeans withdrew from their Jewish friends seventy years ago,” into the effort to “try not to remember Paul Celan.” Celan manifests to warn the poet, “Don’t drink the black milk”—a milk that seems to be the substance of forgetting, of withdrawal, of distancing and calm. And in the penultimate image of this astonishing book, Celan “disappear[s] among the groups of Syrians marching northwards,” the memory of a past atrocity calling us into an ongoing one through this instantiation of absence, disappearance. “How do you know the road to Damascus when you’ve never been down it?” the poet asks, then marks an approach, a hope to live in a reality beyond resemblance, representation, and replacement, a place where “the way to Damascus is not more beautiful than Damascus.” We close the book, just now our fingers stained not with the black milk of forgetting, but something fresher: an ink that refuses to dry.

Hilary Plum is the author of the novel Strawberry Fields, winner of the Fence Modern Prize in Prose (2018); the work of nonfiction Watchfires (2016), winner of the 2018 GLCA New Writers Award for Creative Nonfiction; and the novel They Dragged Them Through the Streets (2013). She teaches at Cleveland State University and in the NEOMFA program, and is associate director of the CSU Poetry Center. With Zach Savich she edits the Open Prose Series at Rescue Press.